eBook - ePub

New Civil-Military Relations

The Agonies of Adjustment to Post-Vietnam Realities

This is a test

- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book provides a conceptual understanding of civil-military relations, a revised framework which accommodates complex and dynamic features of modern political life, focusing on successful adjustments to post-Vietnam realities on the part of the Department of Defense (DOD).

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access New Civil-Military Relations by John P. Lovell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

NATIONAL SECURITY POLITICS AT TOP POLICY LEVELS

9

NATO NUCLEAR POLICY-MAKING

Robert M. Krone

NUCLEAR WEAPONS FOR WHAT?

How to think about nuclear weapons—and, indeed, whether to think about nuclear weapons—have been constant questions since Hiroshima. The controversy over these subjects reached a peak after the 1960 publication of Herman Kahn’s On Thermonuclear War which “attempted to direct attention to the possibility of a thermonuclear war, to ways of reducing the likelihood of such a war, and to methods for coping with the consequences should war occur despite our efforts to avoid it.” 1 Kahn’s following book, Thinking About the Unthinkable, was an analytical response to the emotional reaction of many of his critics that it was immoral to write about such things and, in fact, might make thermonuclear war more possible or acceptable by doing so.2 Now that the controversy has largely passed from the scene, the ten additional years that nuclear weapons have been in existence have brought a slowly evolving realization that such weapons may help to prevent war. The terrible consequences of nuclear war make the search for peaceful alternatives absolutely essential.

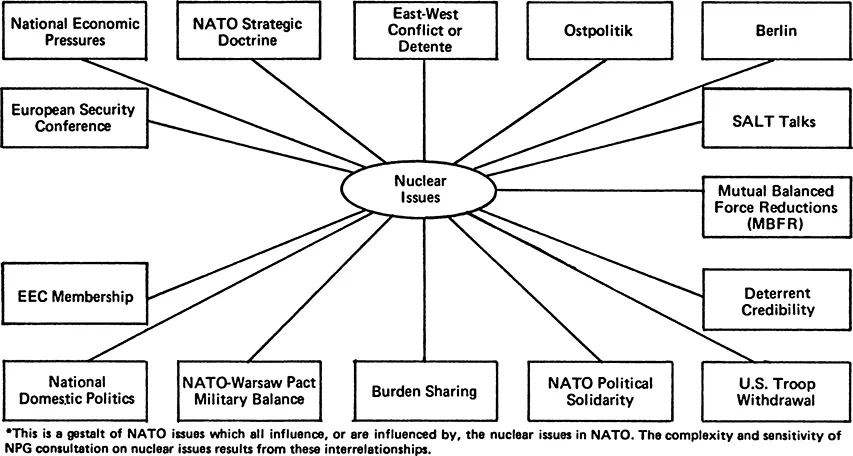

Kahn, Brodie and others also explored some new ideas—that the use of nuclear weapons in warfare would not necessarily result in escalation to a nuclear Armageddon and that peacetime preparations could well be decisive in the survival of large portions of a population or of a nation itself.3 These lessons are a part of the tacit knowledge of NATO nuclear policymakers. Thus, nuclear weapons affect all NATO military operations, plans, tactics and strategy; it is impossible to isolate alliance military strategy from national and international politics (see Exhibit 1).

However, differing views regarding the fundamental purpose of a NATO nuclear arsenal (defense? deterrence? bargaining power? prestige?) have led to differing approaches to related policy issues. The contrasting orientations of military officials on the one hand, and of political officials on the other, illustrate the point at hand. Military authorities have the responsibility for maintaining the military effectiveness of NATO’s forces, while the political authorities, in conjunction with the heads of state of nuclear powers, have responsibility for the decision to use nuclear weapons in defense of NATO. Because political authorities tend to value influence and prestige more than deterrence or defense, and deterrence more than the defense, there can never be complete agreement between political and military officials on approaches to nuclear policy. The military authorities will always be concerned that military flexibility and effectiveness will suffer through the natural inclination of political authorities to increase measures for control over military nuclear procedures, plans and exercises.

As in any pluralistic democratic polity, the values and tacit theories of political and military authorities, combined with their jurisdictional responsibilities, produce competition for control and allocation of scarce resources. The military approach to planning must be conservative, consider the worst case possible, and be based primarily on enemy capabilities. Military requirements are never completely met. The political approach will usually be less conservative, include more of a proclivity for bargaining, and include explicit or implicit estimates of risk and enemy intentions which then guide decisions on establishing priorities for allocating resources. For political authorities, resources for this allocation are never adequate.

Another aspect of the dilemma about the purpose of nuclear weapons is the disparity between the two basic functions of nuclear weapons—deterrence and use—and the strategic and tactical connotations of each of these functions. Most theorists agree that mutual and stable deterrence on the strategic nuclear level has been achieved between the United States and the Soviet Union, since neither has an assured first-strike capability that would deny the other a capability to respond effectively. As the United States possesses a high percentage of NATO weapons and the Soviet Union all of the Warsaw Pact weapons, and since a strategic exchange would destroy both countries, it is “unthinkable” that such an exchange would occur. Furthermore, deterrence (including strategic and tactical components) has worked in the past, is working now, and shows good indications of continuing to work in the future.4

Deterrence, however, is based to a considerable extent on subjective and extra-rational factors such as threats, uncertainties, estimates of intentions, strategy and doctrine.5 All of these factors are nonquantifiable, noncomparable and very difficult to analyze; they can hardly be the basis for explicit policy. Defense factors present a completely different picture, however. The use of nuclear weapons for defense can be analyzed because it is possible to think about objective, quantifiable and comparable factors such as warheads, delivery systems, numbers of weapons, yields and weapons’ effects. Furthermore the technology is predictable to a certain degree. These tangible components which can be precisely compared (“their capability” vs. “ours”) make thinking about nuclear weapons easier.

The irony is that the employment analysis may be much less relevant than the deterrence analysis because the employment analysis is almost entirely theoretical, what Secretary McNamara called “a vast unknown.” There are, fortunately, no nuclear wars from which to extract experience and data.

Most strategic studies and war games concentrate on hypothesizing scenarios for the employment of nuclear weapons because such data can be fed into computers and compared. Since deterrence aspects are subjective and nonquantifiable they tend to get less attention despite their greater relevance. Furthermore, the deterrence aspects and employment aspects of nuclear weapons cannot be separated without violating the reality of any hypothesized scenario except a full-scale strategic exchange in which deterrence factors have all failed to prevent or limit war.

The programs of the NATO Nuclear Planning Group (NPG) suffer from this concentration on employment to the neglect of deterrence. One reason for this is that since the military physically possesses the weapons and has the organized staff to do research it seems natural for political authorities to ask them to engage in studies. The military is best equipped to analyze the employment aspects through strategic-type studies. Analysis of the use of deterrence for war prevention or war termination involves investigating many variables for which the political authorities are primarily responsible. There appears to be no final solution to this dilemma, which is a product of the nuclear age and the relatively short period of time that international political-military nuclear concepts have been under development and experimentation.

The evolution of purpose within the Alliance itself complicates matters even further. Tacit theories which give a participant an answer to the question, NATO for what? also influence that participant’s view of the role of nuclear weapons in NATO.6 There seem to be five fundamental purposes of the Atlantic Alliance which have evolved over the years of NATO’s existence: collective security for the military defense of Western Europe and the containment of communist expansion; political cooperation and solidarity of the 15 nations of the Alliance; scientific, technical, economic and cultural cooperation; detente between East and West Europe; and the search for solutions to societal and environmental problems.

As would be expected, there is a spectrum of viewpoints on the relative priorities of these purposes. Coincident with that spectrum of viewpoints is the range of viewpoints toward the question, Nuclear weapons for what? Although this is a very important problem in NATO nuclear planning, its significance should not be overemphasized. Despite it the NPG political-military consultations process reaches consensus on difficult and sensitive matters of nuclear policy.

WHAT TYPES OF NUCLEAR WEAPONS?

Related to the question, Nuclear weapons for what? is the question, What types of nuclear weapons should be developed and deployed? The issue is one with numerous dimensions, ranging from technology to strategy and tactics, politics and morality.

According to one way of thinking, the bigger and dirtier the weapons the more apt they are to deter enemy aggression. To another, large-yield dirty weapons would provide no alternatives to general nuclear war and conventional defeat or even preemptive surrender.

To one way of thinking small, clean and accurately delivered tactical nuclear weapons are the essential link between conventional weapons and strategic nuclear weapons. Moreover the problems of civilian casualties and unwanted collateral damage would be minimized. To another way of thinking small clean weapons would dangerously lower the nuclear threshold by eliminating the distinction between nuclear and conventional armaments, making nuclear weapons more “acceptable,” and opening the door to an early use of nuclear weapons in a conflict with rapid and uncontrolled escalation.

To some the stockpiling of small clean weapons would insure the credibility of the deterrent. To others such a development would be an unjustifiable expenditure of funds and scientific expertise and merely mean another round in the nuclear arms race. This dilemma, like the others, will not be resolved easily—if at all. How a participant would wish to resolve this dilemma strongly colors his judgments on what the alternatives for the NATO nuclear planning system should be.

THE NUCLEAR THRESHOLD

Another omnipresent issue concerns just where and when nuclear weapons might be used should the necessity arrive: the nuclear threshold issue. Under the massive retaliation strategy of the 1950s there was no ambiguity on this point. Any enemy aggression would, presumably, act as a tripwire and be met by nuclear response—a response which the Soviet Union was not then capable of countering.

With the change to the strategy of flexible response in the 1960s (formally in 1967) immediate nuclear response by NATO is not assumed, although immediate military response to stop the aggression is assumed. Just what this strategy might, would or should mean in terms of graduated response, a raised nuclear threshold and the number of conventional forces needed, became the subject of a controversy on both sides of the Atlantic in the 1960s referred to as “The Great Debate.” 7 That debate will not be resurrected here. It is enough to say that the various perspectives on the problem and how it should be resolved keep the nuclear threshold issue alive. The first variable influencing national views on the nuclear threshold is proximity to the threat—the nations having common borders with Warsaw Pact countries tend to favor policy positions which assure a lower threshold (earlier use) than the Nordic or North American countries.8 The United States is in a unique position on this issue since escalation to a strategic exchange would have a major impact on American cities and populations. The Germans, on the other hand, do not like the idea that the necessary force to stop a Central European Warsaw Pact aggression might be withheld until German territory was overrun, thus presenting two unpalatable options, using a large number of nuclear weapons on their own soil or conceding defeat.9 The second variable is the nation’s position on conventional forces—if the position is that nuclear weapons are a replacement for conventional forces then the acceptable nuclear threshold will be lower than if conventional forces are considered essential. This position is complicated by the inevitable accompanying domestic national political orientation which includes economic, social and moral pressures resulting in a configuration of national priorities which will dictate a peacetime strategy toward conventional forces versus nuclear power. The third variable is national parochialism (the French model) versus internationalism (the Atlantic Alliance model with U.S. nuclear protection); this variable gets to the heart of Alliance rationale. To the extent that Alliance solidarity and successful consultation to maintain solidarity are shared goals, ambiguity over a precise definition of the nuclear threshold will be accepted. The French did not have such a goal, and so used the nuclear threshold issue as one rationale for opting out of the NATO military structure in 1966. Since then there has been tacit consensus that the nuclear threshold should not be precisely defined for two good reasons: the first is that Alliance solidarity might suffer, and second is that the Warsaw Pact’s uncertainty with regard to NATO’s exact nuclear threshold is an important part of deterrence.

CONTROL OF NUCLEAR WEAPONS

Related to each of the issues thus far identified is the fundamental one of the control by member nations of nuclear weapons (with control translating into prestige and ability to mold policy). Because the NPG is the institutional manifestation of a long and continuing debate over control of nuclear weapons, some discussion of the evolution of the debate, and of the structure and processes that characterize the NPG, is necessary to clarify the current status of the issue.10

Exhibit 1: ISSUE INTERRELATIONSHIPS IN NATO*

The interest of European Alliance nations (including the United Kingdom) in active participation in nuclear planning has steadily increased over the past two decades due to a number of post-World War II international trends. In NATO’s first decade, the 1950s, American supremacy over the Soviet Union in strategic nuclear weapons, the Eisenhower administration’s emphasis on massiv...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- Introduction

- The Changing Policy Environment

- Civil-Military Relations at the Community and Operational Level

- National Security Politics at Top Policy Levels

- Conclusions

- Contributors

- Index