![]() I

I

Introduction![]()

Chapter 1

The World of Television

Anne Cooper-Chen

Ohio University

We climbed and rested, climbed and rested. The mountain path was hard-packed in some places, crumbly and slippery in others. After 35 minutes, we reached Danilo's tin-roofed shack, behind his host family's home. With neither running water nor electricity, his Peace Corps "mama" made a fire-cooked meal that restored our energies. After lunch, the family fell back into its normal routine. On a black-and-white TV set, powered by a solar battery on the roof, the tallest antenna I've ever seen brought to the family, dubbed in Spanish, "The Simpsons."

For the Benitez family in the Dominican Republic, whom the author visited in December 2002—as for most global families—television takes its place as "the centerpiece of our entertainment lives" (Merrill Brown, personal communication, July 10, 1989). Entertainment constitutes the largest category of TV content almost everywhere in the world. Now that television is accessible to people in China and India, the two most populous nations on the planet, as well as smaller countries like the Dominican Republic, the medium is a worldwide phenomenon.

The three most TV-saturated countries in the world are China (370 million TV sets), the United States (233 million sets), and Japan (91 million sets; Banerjee, 2002). Now that television truly entertains the world, research about it takes on new importance.

Zillmann and Vorderer (2000) state:

Commercial prerogatives limit research to staking out consumer interest in particular formats without concern for the more fundamental issues of entertainment. These issues must be addressed if media entertainment is to serve the global population better and more successfully in the forthcoming millennium and beyond, (p. viii)

The Latin tenere, root of the word "entertain," means "to hold or keep." The Random House Dictionary (Stein & Su, 1980, p. 290) gives this definition as the word's first meaning: "to hold the attention of so as to bring about pleasure." Barnouw and Kirkland (1989, p. 102) define the term in its modern mass sense as an "experience that can be sold to and enjoyed by large and heterogeneous groups of people." Browne (1983, p. 188) defines an entertainment mass medium as "that which appears to have as its primary purpose the amusement, distraction and/or relaxation of its audience."

The Psychology of Entertainment

Zillmann and Vorderer (2000, p. viii) believe that "more attention, in terms of both theory and research, must be directed at understanding the basic mechanisms of enlightenment from, and emotional involvement with, the various forms of entertainment." Thus their book Media. Entertainment: The Psychology of Its Appeal treats many of the dimensions of this complex subfield of media studies: humor/comedy, drama, violence/horror, sex, sports, talk, music, music videos, and video games. Contributing authors discuss how age and gender can affect choices of and responses to forms of entertainment.

TV ratings indicate a gender difference, for example, in the popularity of various Olympic sports (see chapter 13), but do not explain why these differences exist. In the watching and enjoying of TV sports, researchers who study the psychology of sport spectators consistently find a male bias. When females do watch, they enjoy action and artistic movements, as in gymnastics or ice skating; violence and roughness significantly increase enjoyment for male, but not female, viewers (Bryant & Raney, 2000). Moreover, male viewers truly enjoy the suspense of watching athletic competitions, but females enjoy suspense only "up to a 'substantial' level (point spread 5-9)"; extreme suspense decreases their enjoyment, possibly due to distress (Brvant & Raney, 2000. p. 167).

Mood-management theory posits that people know what works for them—what mode of media entertainment cheers them up or relaxes them; the genre of choice is often comedy. Thus comedy is "a winning formula for media entertainment. More often than not, people do look for merriment by picking comedy with all its foolishness over serious, problem-laden program alternatives" (Zillmann, 2000, p. 51).

Many TV shows labeled as entertainment can also successfully satisfy an individual's cognitive (information-seeking) needs. Chapter 14 describes how one particular show—"Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?"—can satisfy all five of the needs that Katz, Gurevitch, and Haas (1973) identified: cognitive, affective (pleasure-seeking), personal integrative (confidence-building), social integrative, and tension release.

Viewers may initially turn to television for tension release or pleasure, but secondarily gain information—and vice versa; "All media have properties of entertainment," state Fischer and Melnik (1979, p. xiii). "The myth that 'pure entertainment' exists is slowly but surely being dismantled" (Fischer & Melnik, 1979, p. xix).

Information versus Entertainment

The entertainment-education approach to social change rests on this notion of fluid boundaries between learning and enjoying (Singhal, Cody, Rogers, & Sabado, 2004; Singhal & Rogers, 1999). However, the information-entertainment distinction persists. Even the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 19, emphasizes information: "Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive, and impart information and ideas through any media regardless of frontiers" (quoted in Freedom House, 2003).

Freedom House has, since 1979, assessed "information freedom" and "news flow" for all the world's countries (Freedom House, 2003). The organization uses a multitude of data to rate a nation's media (broadcast and print combined) as free, partly free, or not free. Relevant to entertainment content is its score, 0-30, for economic influences on content, such as bias in granting licenses, withholding government advertising, and negative impact of market competition.

The following scores for the countries in chapters 3-12 represent the degree of freedom from economic pressures, from most to least free: Germany, 7; United Kingdom, 7; Japan, 8; Mexico, 9; Brazil, 9; South Africa, 10; India, 12; Nigeria, 16; China, 20; and Egypt, 24. The United States is freer than all of these nations, with a score of 6.

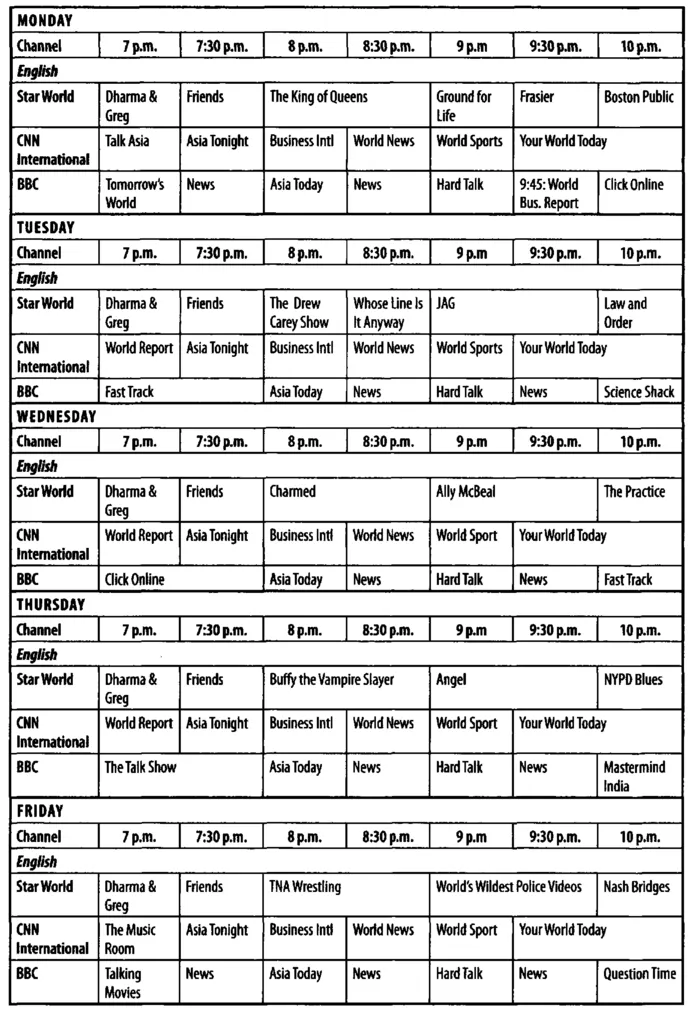

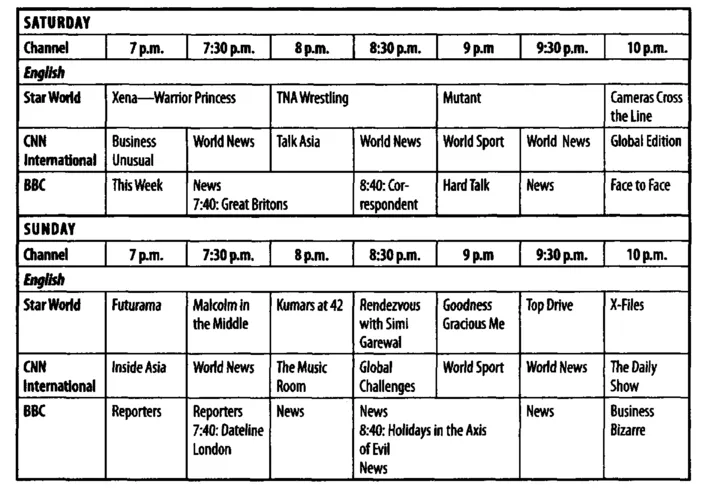

Several factors have worked to create the somewhat artificial distinction between entertainment and informational TV programs. First, an institutional division within TV networks divides news divisions from entertainment divisions; the program grids in chapters 3-12 show the distinct labeling of news shows. Second, an industry-wide division exists between commercial and noncommercial ("educational") television, such as in the dual systems of the United States, the United Kingdom (see chapter 3), and Japan (see chapter 9). Third, entire networks consider themselves as providing either news/information (e.g., CNN, BBC) or entertainment (STAR TV), as the program grid of a multination satellite service shows (pp. 6-7).

The Evolution of Television

Multination TV viewing provided by transnational companies is relatively recent (see chapter 2)—as is television itself, compared to the history of print media. TV experiments started in industrialized countries during the 1930s and 1940s, but World War II halted the medium's expansion. In the

PRIME TIME, SATELLITE SERVICE, ASIA, JULY 2003

United States, television came of age after World War II, in 1948—the first season offering four full network schedules. For half a century, the United States had the most TV sets in the world, but China has since catapulted to first place. Chinese TV viewers can now number as many as 1 billion people, the largest audience on the planet (Chang, 2002).

The period since the late 1980s is often considered the beginning of the "information age," but "entertainment offerings obtrusively dominate media content" so thoroughly that we can say we live in an "entertainment age," as never have human beings had so much entertainment "so readily accessible, to so many, for so much of their leisure time" (Zillmann & Vorderer, 2000, p. viii).

Zillmann (2000, p. 17) refers to the "democratization of entertainment," thanks to television: We have all become nobility—with front row seats that bring to us the "world's greatest actors, singers, athletes, magicians, scholars, cooks, and assorted others." The right to be entertained exists not only in the developed world, but "as more societies become prosperous, this call is likely to be heard around the world" (Zillmann & Vorderer, 2000, p. vii).

Culture and Television

"The technology of communication is, generally speaking, universal; but the contents and functions of communication are culture-bound," says Kato, a media scholar from Japan (1975, p. 6). "A nation's culture," writes Hoggart (1990, p. A-10) of the London Observer, "is always more interesting than its politics."

Within a nation's culture, TV content is one of its most accessible aspects—aside from its cuisine. A tourist need only turn on the TV set in a hotel room, as many cable systems offer abundant overseas fare. In rural southeast Ohio, for example, the Time Warner nonpremium lineup included, in a recent week, kung fu movies on the Action Channel, foreign-language movies on the Independent and Sundance channels, and Japanese animation on the Cartoon Channel.

Definitions of culture vary widely. Servaes (1988, p. 843), also a mass media scholar, defines culture as "a phenomenon whose content differs from community to community. Therefore, as each culture operates out of its own logic, each culture has to be analyzed on the basis of its own 'logical' structure." According to Martin (1976, p. 430), "Culture, like communication, may be thought of in terms of a continuum. Culture ranges from an individual's unique patterned ways of behaving, feeling and reacting to certain universal norms that are rooted in common biological needs of mankind." To Real (1989, p. 36), author of Supermedia, culture is "the systematic way of construing reality that a people acquires as a consequence of living in a group."

Cultural Anthropology

The deepest understanding of culture, however, comes from the field of cultural anthropology (Bernard, 1988), one of four approaches to studying non-Western cultures, along with linguistics, physical anthropology, and archaeology (Ulin, 1984). According to Geertz (1973, p. 4), culture is the concept "around which the whole discipline of anthropology arose." Clifford Geertz ranks as one of 21 "late 20th century theorists" that Beniger (1990, p. 710) isolated in the 1,800-page International Encyclopedia of Communication. Geertz (1973, p. 5) defines culture as "the webs of significance [manl himself has spun."

"All anthropological approaches to culture center, however, on regularities within cultural patterns, explicit or implicit," writes Briggs (1989, p. 437). "Culture is seen as being transmitted from one generation to the next through symbols and through artifacts, through records and through living traditions." Taylor, in Primitive Culture, published in 1871, defined culture as that "complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, customs and many other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society" (quoted in Briggs, 1989, p. 437).

Similarly, Kottak (1989, p. 5) defines culture as "knowledge, beliefs, perceptions, attitudes, expectations, values, and patterns of behavior that people learn by growing up in a given society." To an anthropologist, "not just university graduates, but all people are cultured" (Kottak, 1989, p. 8). Enculturation is "the process whereby one grows up in a particular society and absorbs its culture" (Kottak, 1989, p. 8).

Kottak (1989), for example, studied television in Brazil, using content analysis, interviews with experts and TV personnel, archival and statistical research, and field study at six rural communities. Anthropologists pursue this central question regarding culture (Kottak, 1989, p. 14): How is cultural diversity both influencing and being affected by larger forces?

Kottak's inspiration came from Clifford Geertz, who studied premedia society in Bali. Geertz (1973, p. 23) refers to anthropology's "deepest theoretical dilemma: how is [cultural] variation to be squared with the biological unity of the human species?"

Global Diversity

Hofstede, a social scientist from the Netherlands, can shed light on Geertz's dilemma. Hofstede (2001, p. 9) defines culture as "the collective programming of the mind that distinguishes the members of one group or category of people from another." Hofstede originally developed four dimensions of cultural variability through anal...