![]()

PART

III

Policy

![]()

CHAPTER

7

Regulatory Concerns

Robert Pepper

Federal Communications Commission

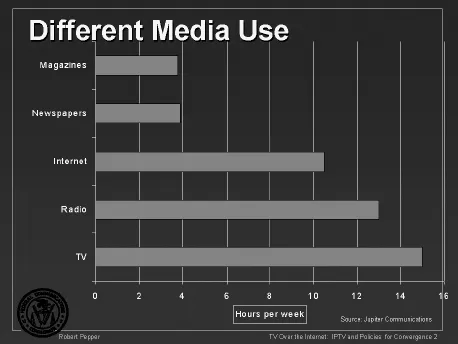

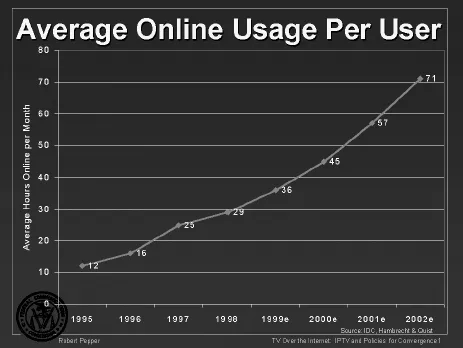

The domestic consumer content industries in the United States include broadcasting, film, radio, TV, cable TV, computer application software, video games, Internet online content, newspapers, books, and so on. All of these account for almost one third of a trillion dollars per year (Fig. 7.1). In addition, U.S. domestic transmission network revenue amounted to one third of a trillion dollars per year. In addition, U.S. domestic transmission network revenue also amounted to one third of a trillion dollars in 1999 (Fig. 7.2). Thus, what is at stake is no less than the potential restructuring of two thirds of a trillion dollars per year in revenues, and the communications industries as they are known today.

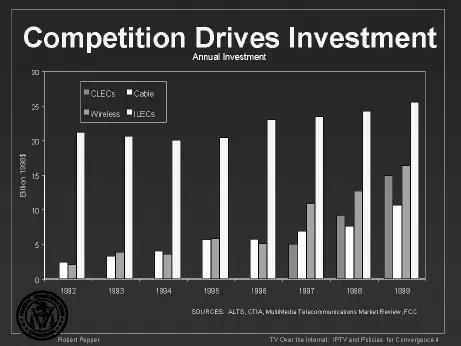

New entrant competitors are beginning to enter the U.S. market, investing capital and building their own backbone networks. Investment in new U.S. networks and infrastructure doubled in real dollars over the 4 years beginning just before passage of the 1996 act to $60 billion per year, and ending with the downturn in dot-coms and telecommunications (see Fig. 7.3). The most dramatic growth has been in the new entrants in wireless communication. The incumbent local exchange carriers’ capital investments in constant dollars were flat or slightly declining until they faced competition, at which point they increased infrastructure investment by about 15%.

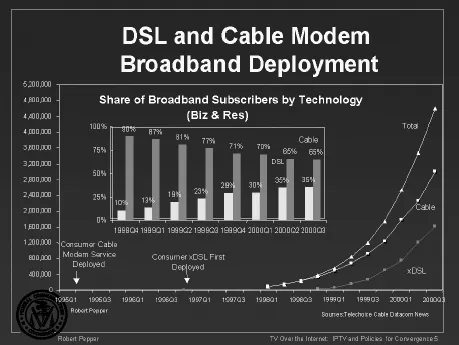

There has been a competitive deployment of broadband among digital subscriber loops (DSL) and cable modem service (Fig. 7.4). But how far along is the deployment cycle? DSL is a technology from the 1980s. Cable modems were talked about in the late 1980s and early 1990s. The first commercial cable modem was deployed in 1995 and the first commercial DSL in 1996. The inflection point was in 1998. At the beginning of 1998, there were about 50,000 cable modems. By the end of that year, there were about 500,000. The next year, 1999, began with 35,000 DSL lines and ended with 550,000 lines (see Fig. 7.5).

It is clear that a competitive dynamic between the local exchange carriers and cable companies developed that has driven competitive deployment and adoption of these two broadband services. At the end of 2000, there were approximately five million high speed Internet access consumers with cable modems and DSL in the United States. Things appear to be on the steep slope of the classic adoption “S-curve.” This is important because it will enable the interactive market to develop, assuming other things do not get in the way.

POLICY

The regulatory framework in the United States, and the rest of the world, is based on a set of old rules and assumptions. The old rules were based on distinct industry and regulatory structures. The old rules and regulatory structure were based on noncompetitive models. They assumed a scarcity of spectrum, natural monopolies, or regulated oligopoly. The government protected the incumbents, thus insuring scarcity. The thought was that it was necessary to regulate a natural monopoly. Over the last decade, it became clear that it was an unnatural monopoly, created to a large extent by government decisions to protect incumbents in order to stimulate investment. In the name of protecting consumers, the government created barriers to entry and decided winners and losers. Licenses were given to people who promised all kinds of wonderful things, and they were never kept to their promises. In fact, the result was what some have referred to as regulatory capitalism, where one invests in lawyers and lobbyists instead of technology and services. Those old rules are being challenged.

Digitization is driving the change. It creates conditions for competition, and reduces entry costs. Innovative services and products at much lower costs have been introduced. Businesses today have the flexibility to combine different products and services. CNN online and the New York Times Web site are new media combining text, pictures, streaming audio, and streaming video. All of the communications regimes are going digital. The industry boundaries are beginning to blur and digitization makes the old regulation of industry structures obsolete. The neat little silos used in the past are no longer applicable going forward.

Digitization also destroys compartmentalization. A bit does not know if it is a broadcast bit, a cable TV bit, a telephone bit, or a computer networking bit. The bit can be transmitted seamlessly; it is neutral to the medium of transmission. It can be stored, processed, manipulated, and forwarded. Intelligence can be everywhere in the network and at the edges. It is a false debate between smart networks and dumb networks. There will be both, with intelligence in the networks and at the edges. How all that sorts out will depend on the market and not regulation.

These new realities are confronting the old rules and structures. The old rules that were based on distinct industries and structures were written at a time when the nature of the conduit determined the content. The content came with the conduit. With digitization, these are no longer necessarily linked. This leads to interesting developments.

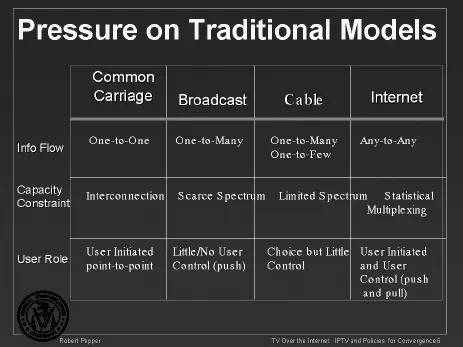

The traditional regulatory approaches that kept communications industries within traditional boundaries will not work anymore (Fig. 7.6). This is not just a matter of regulation, but of changing business models. This is difficult because change is especially difficult for incumbents, and in the telephone world some incumbents are 120 years old.

In the traditional world of telephony, information flow was always one-to-one. The capacity constraint was essentially the switch. The network was designed on the assumption that not everyone wants to call at the same time. When they do, the result is busy networks. In broadcasting, the architecture is one-to-many and the capacity constraint is the radio spectrum. And, there is essentially no user control. TV and radio were the first effective push technologies. This architecture is extremely efficient when many people are watching the same thing, but it is constraining from the user’s perspective. The nature of information flow on the Internet is many-to-many. The constraint is bandwidth, or the transmission speed of the connection. And the use is user initiated and controlled, push and pull.

There are a number of important questions facing IPTV. IPTV may refer to Internet protocol TV, interactive personal TV, or intelligent personal TV. It can mean different things. Actually, it is all of these because the market will determine how it develops.

Will Internet TV be evaluated by looking forward or backward? Is it necessary to look forward in terms of new market policy and consumer models or should the old models be allowed to drive what will happen in the future?

Intellectual property rights (IPR) are a major question. (See Carter, chap. 9, and Einhorn, chap. 10.) Will they be used as an enabler or a barrier? Who controls the content, the gateway or the customer? Although intellectual property rights holders need to be compensated for their intellectual property, 19th- or early 20th-century models for intellectual property rights protection and compensation may not work going forward. IPR may become one of the biggest barriers to the development or deployment of Internet TV whether it is Internet over TV or TV over the Internet. Copy protection issues and compensation are key when considering linking content and conduit. Intellectual property right protection issues are holding back the development of new media. People will need to figure out different ways to get paid. Fortunately, the willingness to pay is exceeding anything once thought possible. Eighty percent of Americans pay for their TV today in the form of cable or satellite. Because the willingness to pay is so high, it should be possible to develop a new IPR model to make it an enabler of the new Internet-based service.

POLICY DOES NOT EQUAL REGULATION

There are many policy issues related to TV over the Internet. For truly interactive TV with purchasing on the web, how should privacy and information use be handled? In the cable TV world, there are very specific limitations on what the cable operator can do with subscriber identifiable information—basically nothing without subscriber permission. In the telephone world, there are limits on customer proprietary network information. Can there be comparable protections for TV over the Internet?

Another concern is how to protect children, not just from pornography but also from terrorism, gambling, or the sale of alcohol over the Internet. There also are issues concerning electronic commerce transactions over TV, over the Internet, not to mention taxation, tariffs, uniform commercial codes, and trust. These t-commerce issues and their resolution are really no different than the general e-commerce questions. However, there are people that want to impose general media rules on top of the Internet. That would be extremely counterproductive.

INTERNET TV COMPETITION REGULATION AND POLICY

The question is, why is legacy media regulation necessary on the Internet when there is no scarcity? This goes to the question of incumbents creating scarcity and the government maintaining it in order to justify regulation to protect consumers because there was scarcity. Rules were used as a shield against competition. This is not new. Broadcasters argued for decades that cable TV would destroy broadcast TV and the consumers would be worse off. So broadcast TV was protected from cable for 30 years. Then the cable industry argued that satellite TV would harm cable TV. Each industry argues that competition is good just as long as they are entering someone else’s market.

The Internet is not a traditional electronic mass medium. Attention must be paid to the incumbents arguing for a “level playing field” to slow competition. Putting those old media content rules on the Internet would be counterproductive.

The decision was made not to regulate the Internet by not imposing legacy telecom regulation, calling this “unregulation.” Several lessons have emerged from this policy. First, there are real benefits from not imposing old rules designed for monopolies on new services and entrants. Second, when the new services compete with the legacy services, regulatory parity can be achieved by deregulating the incumbents rather than regulating the new entrants. Third, there is still a need to worry about bottlenecks and anticompetitive behavior, especially from former incumbent monopolies.

In general, however, regulators should be promoting rather than prohibiting. The issue at hand is not about traditional media regulation, but rather about enabling entirely new platforms for new, innovative, and competitive services that consumers will value. Policymakers will need to take the same forward-looking perspective as technologists and investors.

![]()

CHAPTER

8

The Challenges of Standardization: Toward the Next Generation Internet

Christopher T. Marsden

Re: Think and The Phoenix Center

The mass distribution of video programming over IP networks promises a richer experience for viewers, with widely predicted increases in interactivity, choice, personalization, and the ability to micro pay for a la carte programming.1 Whereas broadcasting was licensed, controlled, and tightly regulated by national governments (or even owned as a monopoly service), video-over-IP will be delivered by international market mechanisms with both relatively minimal direct legal restraint and little direct government strategic intervention. Standardizing video delivery to produce network economies of scale and scope will require international corporate coordination between the converging industries of broadcasting and video production, wired and wireless telecommunications, and computer hard- and software derived data communications. In this economic analysis of law, I consider the distribution of existing television broadcasting archive over IP-based ne...