The Italian jurist Andrea Alciato, one of the founders of the modern legal tradition, was much more famous in his day for a book of satirical emblems than for any of his learned treatises on the meaning of legal words. He was more widely known, much better read, and of far greater popular influence on account of his Little Book of Emblems – Emblematum libellus – than for any of his juristic writings. Alciato’s emblems, first printed in 1531, went to over 200 editions in the following two centuries.1 It was the first book of its kind. In a single accidental stroke he founded the genre of emblem books and his illustrated epigrams or formulae were repeated by countless followers, imitators and epigones. An untold success and yet the book, according to Alciato’s letter to his publisher was a joke intended for a friend on the occasion of the Saturnalia.2 It was composed during the course of the festival (festivis horis) and was intended to create pleasure, to surprise, to alleviate boredom, to allay sorrow, to prick the spirit, to inspire and to arouse.3 As the choice of the Latin libellus suggests, the book was satirical, fundamentally radical and in a more modern idiom, potentially libelous.

The emblems that Alciato sent to his publisher were humorous, moralizing, and on occasion obscene epigrams to which the publisher Henri Steyner brilliantly, if fortuitously, added illustrations, generally vignettes that visualized the humour and the moral of the written apothegm by reference to classical figures. As he put it: ‘It seemed to me highly useful to provide a few simple engravings so as to signify the author’s profound meanings’ which would otherwise remain closeted in the domain of erudition. Take a simple example. Emblem 157 of the 1551 edition is titled in vitam humanum or on human life. Under the winds of humour, venti ludibrium, portrayed by a bending tree and fleeing clouds, the two philosophers Democritus and Heraclitus are in conversation. Their books have fallen to the ground, seemingly discarded. Heraclitus, passively sitting, and looking down at the ground, weeps. Democritus, active and gesticulating, laughingly announces that ‘Life has become increasingly ludicrous.’4 Here are portrayed the two aspects or Janus face of philosophy: misery and joy. Depending upon which option is chosen, it is what contemporaries of Alciato would have viewed as a heraclite or democratizing image: Democritus, the philosopher of laughter chides the melancholic Heraclitus for his lack of humour and his failure to get outside of his books, the ratio or scripture of law.

1 Questions of genre

It is abundantly apparent from Alciato’s letter to his publisher and again from the epistle to the reader that whatever the moral or legal intentions of his book of emblems, it is also gauged to amuse, its end is pleasure (voluptas) and this is fitting enough to its occasion, that of the celebration of the New Year’s holiday. Although authored by a lawyer, the little book was not in any immediately apparent sense a law book, though equally obviously it was connected to law both by virtue of the author’s profession and by dint of the numerous legalisms portrayed in the emblems themselves. Many standard juridical themes are indeed played out, including several images depicting justice (iustitia), sovereignty (princeps), compact (concordia), good government (res publica), amity (amicitia), enmity (hostilitas), wisdom (prudentia) and legal scholarship (studium). The subject matter of the images and epigrams was largely classical and so included numerous legal commonplaces relating to justice and judgment even if the treatment of these themes, as we will see, was more radical and erotic than would usually be the case in legal texts. The question of content, however, is subordinate to that of genre and form.

The title of the work, and specifically the word libellus provides a clue as to an important ambiguity. Its primary referent according to Lewis and Short’s Latin Dictionary is indeed little book, but the word also has a secondary and equally common meaning of legal petition or charge. Amongst the further connotations listed are lawyer’s brief, letter and libel. To this it can be added that in later Latin, with which Alciato would have been equally, if not more familiar, libellus took on the meaning of charter or deed, as well as to sue, and by extension writ or libel.8 Already captured in the title and the various other prolegomena to the emblems is a striking conjunction of the playful and the legal, of the rhetorical and the juristic, of the hedonistic and the forensic. They are in one Roman idiom quasi-legal, meaning to be treated ‘as if’ they are law or writ, even if they are both less and more than that. And that is not all, the later connotations of libellus add a further dimension of meaning: if the emblems are charters or deeds, they are foundational, they institute their object or create the subject to which the emblem will attach. The libellus here signifies a series of obligations, the bonds or norms, the vinculae that will hold the subject in place. In modern terms, in the context of the cold positivism that we have inherited from the nineteenth century, these conjunctions of the legal and the extra-legal, these mixtures of norm and image, appear to be extravagant and at the very least unscientific and so require some further explanation.

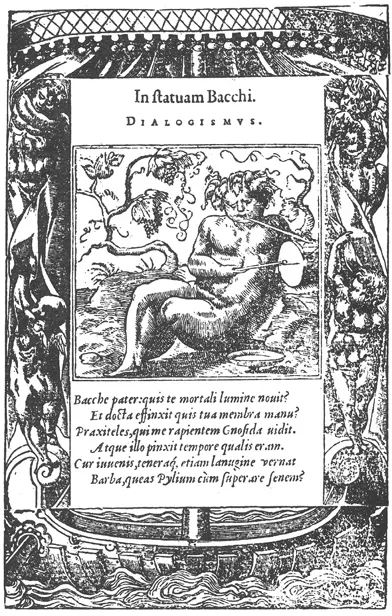

Start with a slight digression. Emblem 25 provides an intriguing and relevant image of wisdom (prudentia). Entitled In statuam Bacchi (Figure 1.1), an image of Bacchus, the emblem portrays a naked Bacchus, a garland on his head, seated under vines with a bowl of wine in front of him. He is playing with a toy drum and waving a rattle in his mouth. The picture is framed as if Bacchus is upon a stage with the proscenium arch composed of naked boys. In later versions of the emblem Bacchus is placed on a pedestal and surrounded by an arbor, nature’s stage.9 What is visualized in the image is an enactment, an acting out of the epigram, and in that sense all emblems are theatrical. Many emblem books, just to instantiate the point, were published under the title Theatrum. The theatrical has a public significance but it is equally and archetypically a play and playful in conveying the contingency of mortal things. What is presented in the image of Bacchus is quite clearly a theatrical representation, a risky image, one that is in part comedic, and in part an erotic message. Bacchus or in Nietzsche’s Greek terminology Dionysus or Dithyramb had his festival, called Lenaea, in January, the saturnalia for which Alciato originally composed his Emblemata. That is perhaps a coincidence or at least it is unremarked by the commentators on the work but it does potentially help to signify the importance of this emblem to the project of the book.

As is well known, Aristotle defined law as ‘wisdom without desire’10 and yet Alciato inverts that maxim and represents Prudentia, the wisdom that presides over legality, by means of an image of a nakedly desiring divinity. The implication that wisdom and lust are connected, that knowledge depends upon desire, that law and love are mutually dependent, is a founding pillar of gay science and it is one of the constitutional axioms of emblematics. It gains its finest expression in the work of Alciato’s contemporary Rabelais, whose discourse on drinking proffers the maxim that ‘I have the word of God in my mouth, Sitio.’11 Elsewhere and more fulsomely, Gargantua proclaims: ‘I drink for the thirst to come. I drink eternally. This is to me an eternity of drinking, and drinking of eternity.’12 In another potent image, the tears of Christ, O lachryma Christi, are pure wine.13 The connection runs from

Figure 1.1 In statuam Bacchi. On a statue of Bacchus

divinity to doctrine, from lust to law. For Alciato too, wine augments knowledge, as is explicitly stated in emblem 22 – vino prudentiam augeri. It has its dangers but nonetheless in vino veritas, wine will untie the tongue and reveal the secrets of the heart or, to quote the final line of the epigram to Bacchus: ‘my throat is open wide, you flow sweetly’. Wine is here what we might now call the royal road to the unconscious, the fast path to the truth of the subject, the key to the secrets of interiority. Implicit also in that image is the explicit suggestion that wisdom is nothing without pleasure, that knowledge must seduce, and that law, to be effective, has to take its hold upon the inside – ‘the Law hits us from the space of the imaginary’.14

Turning then to the question of genre, this gay science, this emblematic lust or desiring law falls more within the bounds of the epideictic or ceremonial than it does within the traditional ambit of the forensic or of law. In part that is because the status of rhetoric and the classification of genres has changed. Epideictic rhetoric was traditionally the genre of religious practices, of rites and rituals that would bind (religare) the subject to the social. The epideictic was the discourse of public office and of social events. Great men were praised, great deeds were honored, civic functionaries were lauded and blamed, the dead were celebrated, and the occasions of the ecclesiastical and civil state, whether honorific or festive were marked and relayed. The epideictic genre was classically the most expansive and immediate of the branches of rhetoric. It dealt with matters of life and death, the eulogy and the encomium, it linked human events to divine purposes, seeming accidents to underlying laws and thus it was present in or crossed over into all of the genres of public discourse.

There is a danger that today we think of the epideictic or ceremonial as merely ornamental or simply hedonistic. Little sense of history, however, is needed to point out that the opposite was and is the case. The epideictic may have changed in terms of the content and especially the media through which the emblematizing of the social occurs, through which law takes hold, but the rites and ceremonies through which the social is staged have, if anything, increased in prevalence and complexity.15 That trajectory towards the mediasphere apart, the epideictic always potentially incorporated the forensic and deliberative and by the time that Alciato was writing ‘all literature became subsumed under epideictic, and all writing was perceived as occupying the related spheres of praise and blame’.16 Everyone to whom speech was addressed was, as Aristotle opined, your judge and hence the unavoidable interplay of genres, of ritual and law, of ceremony and rule.17 It is not that law and ritual, forensic and epideictic rhetoric are identical but rather that at the time that Alciato was writing, the law was a subdivision or branch of the ceremonial. The social presence of law depended upon the threatre of the Court and the rituals attached to an itinerant judiciary or majestic trials. The technical discourses of lawyers, the arguments of advocates and the linguistic intricacies of juridical texts would be nothing without a prior space of social approbation or established modes of engaging with or attaching to the subjects whose lives law fabricates and commends.

The general function of the ceremonial was to give credence to law, and effect to rule. Ceremonies, rites and festivals all had a serious purpose. They held the social together, they solemnized the interactions that expressed or represented the communal bond and the general tone of such rituals of self-affirmation was that of tedious repetition, of earnest gravity, and of opaque or enigmatic complexity. The content of the ceremonial was generally hieroglyphic, Greek or Latin, and so delphically attractive or impressively seductive without being accessible in the vernacular. Alciato wrote at a time when the vernacular was just emerging in print, while Latin still ruled but with its days numbered and running out. The epigrams that Alciato composed in Latin were intended initially for ...