![]()

1

The Great Cultural Tsunami of Fairy-Tale Films

Jack Zipes

Fairy-tale films have been swamping big and small screens throughout the world ever since the beginning of the twenty-first century, seeking to overwhelm audiences with innovative and spectacular adaptations in a kind of globalized cultural tsunami. Indeed, journalists and critics often talk about a phenomenal surge or tidal wave of fairy-tale films, and wonder why and how this seemingly perplexing cultural phenomenon originated and spread. Meanwhile, numerous contemporary cinematic fairy-tale films continue to draw attention by shattering and altering the global public’s understanding of traditional fairy tales with happy endings. Though many films are frivolous spectacles, an impressive number are fantastic pastiches and explorations of classical tales that stretch the imagination of viewers in unusual ways.

Discussing the web of fairy-tale transformation, circulation, and reception in the twenty-first century, Cristina Bacchilega remarks:

The contemporary proliferation of fairy-tale transformations in convergence culture does mean that the genre has multivalent currency, and we must think of the fairy tale’s social uses and effects in increasingly nuanced ways while asking who is reactivating a fairy-tale poetics of wonder and for whom. Even in mainstream fairy-tale cinema today, there is no such thing as the fairy tale or one main use of it. This multiplicity of position-takings does not polarize ideological differences, but rather produces complex alignments and alliances in the contemporary fairy-tale web.

(2013, 28)

The more unusual and usual twenty-first-century position-takings in fairy-tale film production come from a variety of directors and countries. The diverse examples offered below will serve to contextualize the critical analysis later in this chapter.

In France, Catherine Breillat produced a new sexually loaded feminist version of “ Sleeping Beauty” in 2010 that made her provocative “Bluebeard” film of 2009 appear tame; while Christophe Gans created a spectacular and lavish Beauty and the Beast (La Belle et la Bête 2014) in an attempt to supersede Jean Cocteau’s great classic, La Belle et la Bête (1946). In South Korea, there appears to be a trend to turn fairy-tale films into horror films that led to Kim Jee-woon’s terrifying adaptation of a Korean folktale, A Tale of Two Sisters (2003); Yong-gyun Kim’s transformation of Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Red Shoes” into a gory mystery (2005); Man-Dae Bong’s Cinderella (2006) into a scintillating trauma; and Pil-Sung Yim’s chilling Hansel & Gretel (2007) into a dramatic defense of children.

However, horror is not just reserved for South Korea. British director Iain Softley produced the disturbing Trap for Cinderella (2013), about an amnesiac young woman traumatized by a fire that killed her best friend and left her without a sense of her real identity. In another British film, The Selfish Giant (2013), directed by Clio Barnard, Oscar Wilde’s famous fairy tale is totally transformed into a tragic story about two working-class boys who seek to make themselves rich in a swindling owner’s junkyard.

While the fairy-tale films of other countries may yield less horror, the prospects for innovation remain high. After great success with such animated films drawn from West African folklore as Kirikou and the Sorceress (1998), Kirikou and the Wild Beasts (2006), Azur and Asmar: The Princes’ Quest (2006), and Tales of the Night (2011), the talented French filmmaker Michel Ocelot produced a charming didactic prequel, Kirikou and the Men and Women, in 2012. In it, the tiny nude hero once again comes to the rescue of his villagers in five different stories told by his grandfather. Of course, when it comes to animated films, the great Japanese filmmaker Hayao Miyazaki has had a profound influence on directors throughout the world with such works as Spirited Away (2001), Howl’s Moving Castle (2004), and Ponyo (2008). Miyazaki’s and Ocelot’s works demonstrate without deliberate artifice that animated fairy-tale films can stimulate critical reflection, pleasure, and joy by not following a conventional Disney schema.

Miyazaki’s direct influence in Japan can be seen in the beautiful and sumptuous hand-drawn film, The Tale of the Princess Kaguya (2013), directed by Isao Takahata, which is based on a Japanese folktale, “The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter.” There is no happy ending in this film that recounts the struggles of a miniature girl discovered in a bamboo shoot to determine her own destiny, and yet, after Kaguya realizes that she is a moon resident and must return to the moon, one can only admire her true natural nobility when she unwillingly departs for the moon. Moreover, like many of Miyazaki’s films, Takahata’s story is striking because it uses traditional hand-drawn animation in unconventional ways that go beyond the Disney model.

Indeed, some American “non-conventional” stop-animation films have also gone beyond Disney and suggest that they have been influenced more by Miyazaki than by Disney. For instance, ParaNorman (2012), directed by Sam Fell and Chris Butler, explores how Norman, an eleven-year-old boy in the small Massachusetts town of Blithe Hollow, is mocked, bullied, and marginalized because he visualizes and speaks with his dead grandmother and other ghosts victimized by witch hunts of the past. With the help of a book of fairy tales and compassion for the persecuted “witch” Agatha, Norman saves the town from a catastophe, and the former outcast becomes a hero.

Similarly, in The Boxtrolls (2014), directed by Graham Annable and Anthony Stacchi, a young boy by the name of Eggs is treated as a dangerous provocateur, who lives with the monstrous scavengers called boxtrolls. In reality, these creatures are merely peaceful and harmless souls who collect discarded items to build unusual machines in the underground, while the pest exterminator, Archibald Snatcher, is the real monster, who seeks to exterminate the boxtrolls for his own profit. But Eggs exposes him and becomes the town’s hero instead of an outsider. In both these films, marginalized young boys dramatically oppose the norms of society, and the digitalized animation that reflects their struggles is innovative, the images, enthralling, and the characterization, extraordinary.

Stop-motion digital animation will probably dominate fairy-tale filmmaking in the years to come and produce such mainstream dreadful films as the American disaster, Strange Magic (2015), directed by Gary Rydstrom and produced by George Lucas, which Justin Chang calls “mirthless and derivative” (2015), but they will be contested from the margins of the cultural field by such films as Jack and the Cuckoo-Clock Heart. In a review published in Variety, Peter Debruge describes the film this way:

A boy born on the coldest day on Earth survives only by the grace of a magical ticker in “Jack and the Cuckoo-Clock Heart,” a Steampunk rock musical reverse-engineered from an album by French band Dionysos and the popular tie-in book written by its frontman, Matthias Malzieu. Co-directed by Malzieu and musicvideo helmer Stephane Berla, this charming yet oddly miscalibrated computer-animated fairy tale combines gothic, Tim Burton-esque elements with a younger-skewing porcelain-doll look, confusing auds as to who’s being targeted exactly. The answer; no one in particular, as Malzieu seems to be making this idiosyncratic, overly precious film mostly for himself.

(2014)

Whether this last comment is true, this extraordinary film uses fairy-tale motifs of a frozen heart, noble quests, and the joys of art in such a charming manner that its unique eccentricity can be shared by audiences worldwide and not just enjoyed by Malzieu.

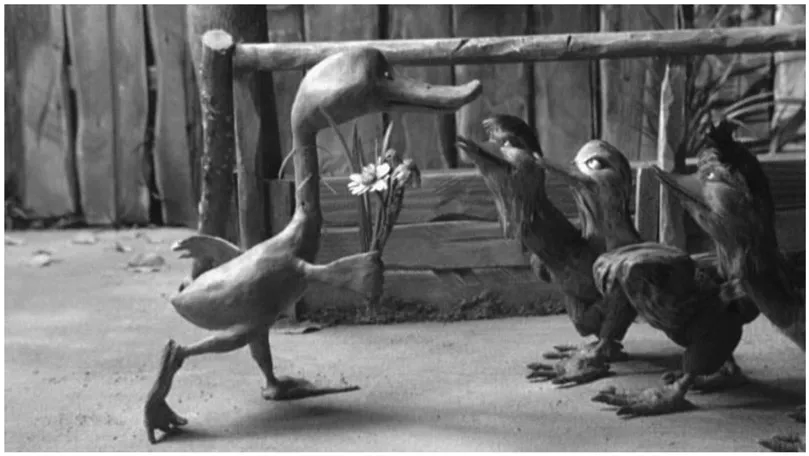

Other directors still rely on more traditional animated techniques to capture such eccentricity. For instance, the fabulous Russian animator Garri Bardin continues to use clay animation and has stunned audiences with his beautiful, politically charged The Ugly Duckling (2010), which cleverly transforms Andersen’s tale into a parody of pretentious Russian glory and oligarchy, and which satirizes the changes that have supposedly occurred in the “new Russia” (see Figure 1.1). Here a gentle innocent duckling rises above the dilapidated barnyard symbolic of present-day Russia to embrace the freedom of flying on his own.

Figure 1.1 The Ugly Duckling/Swan mocked by real ducks, The Ugly Duckling (2010).

Turning back to live-action fairy-tale films in our discussion of works that comprise the cultural tsunami, I should like to note some other diverse experiments. For instance, Sheldon Wilson and Catherine Hardwicke, two American directors, introduced werewolves into their versions of “Little Red Riding Hood” in Red: Werewolf Hunter (2010) and Red Riding Hood (2011), seeking to titillate audiences with bizarre incidents and contrived plotlines. In contrast, Czech director Maria Procházková’s brilliant Who’s Afraid of the Wolf? (2008) retold the same famous tale from the perspective of an imaginative six-year-old girl, probing the capacity of children to deal imaginatively with family conflict. While not directly adapting “Little Red Riding Hood,” Joe Wright’s thriller, Hanna (2011), constantly alluded to the tale in his pastiche depicting a savvy young girl who learns to take care of herself in a world filled with predators.

Of course, “Little Red Riding Hood” is not the only classical fairy tale which has been cinematically re-envisaged. There has also been a wave of fairy-tale films about “Snow White” such as American productions like Tarsem Singh’s Mirror, Mirror (2012), Rupert Sanders’s Snow White and the Huntsman (2012), David DeCoteau’s Snow White: A Deadly Summer (2012), Rachel Goldberg’s Grimm’s Snow White (2012), Pablo Berger’s Blancanieves (2012), and Jacco Groen’s Lilet Never Happened (2012). In addition, “Hansel and Gretel” has received special attention in such diverse films as Mike Nichols’s Bread Crumbs (2011), Tommy Wirkola’s Hansel & Gretel: Witch Hunters (2013), David DeCoteau’s Hansel & Gretel: Warriors of Witchcraft (2013), Duane Journey’s Hansel & Gretel Get Baked (2013), and Danishka Esterhazy’s H & G (2013). Adaptations of Andersen’s “The Snow Queen” include David Wu’s Snow Queen (2002), Julian Gibbs’s made-for-TV musical The Snow Queen (2005), and Chris Buck and Jennifer Lee’s well-made film for Disney fans, Frozen (2013), which has won many awards for seeming to be an untypical Disney film while once again merely celebrating elitism, the sentimental American musical, and, most importantly, the Disney brand. The other live-action Disney films of this period, Tim Burton’s Alice in Wonderland (2010) and Robert Stromberg’s Maleficent (2014), tend to break from the conventional corporate model and may indicate a more serious feminist approach by the Disney studio to traditional fairy tales. Of course, as Burton’s Sleepy Hollow (1999) and Corpse Bride (2005) indicate, his predilection for endorsing weird outsiders will always make his interpretations of fairy tales somewhat unconventional.

Returning to animation, Tomm Moore and Nora Twomey created an unusual Irish fairy-tale film with The Secret of Kells (2009), which combines legend with folklore and depicts the struggles of a young apprentice named Brendan to save an illuminated manuscript of the Bible from the invading Vikings during the eighth century. In the course of the action he is aided by a pagan forest spirit whose presence brings out the sacred relationship between religion and nature. In 2014 Moore directed another superb Irish fairy-tale film, Song of the Sea, based on tales about the marvelous Selkies, which poignantly portrays a young boy’s quest to save his sister and fulfill a promise to his dead mother. But it is not so much the sentimental story that is so compelling in this film, it is its aesthetics. As Carlos Aguilar has written in the Toronto Review:

Resembling rustic watercolor paintings enhanced with movement, there is an artisanal quality to every frame. From the sea, to the city, to the forest and the fantastical underworld, the amount of details employed in every creature and space is breathtaking. Nothing is overlooked. So meticulous is their approach that even transmission towers have a distinct design. Unattainable by solely using computer animation, the film’s visual aesthetic feels simultaneously handcrafted and otherworldly. Filled with a classical warmth, “Song of the Sea” should remind everyone why animation, when done as flawlessly as it is here, is such an incredible medium. Color, form, and fluid motion delivered in an unforgettable style that’s at the service of a similarly compelling story.

(2014)

In another tender American film, based, this time on folkloric Viking stories, Dean DeBlois and Chris Sanders created a startling film about war and peace that depicts dragons as “the others” in How to Train Your Dragon (2010). Unfortunately, DeBlois’s sequel, How to Train Your Dragon 2, despite some beautiful digital landscaping, is a lamentably sentimental film that borders on glorifying war instead of peace. Following the great success of the first Shrek (2001), directed by Andrew Adamson and Vicky Jenson, Shrek 2 (2004), Shrek the Third (2007), and two further “Shrek” films have appeared, Shrek Forever After (2010) and the spin-off Puss in Boots (2011). The commerical marketing of these mediocre sequels has diminished the poignancy of the original film, which thrived on its hilarious critique of Disney conventionalism. The sequels rendered the “Shrek” narrative predictable and conventional; Puss in Boots was irritatingly boring. Fortunately, the animated Brave (2012), directed by Mark Andrews and Brenda Chapman, stirred a debate about feminist fairy-tale films just as the live-action trilogy, The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey (2012), The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug (2013), and The Hobbit: The Battle of the Five Armies (2014), directed by Peter Jackson, gave rise to a quarrel about the proper way to adapt J.R.R. Tolkien’s fairy-tale novel for the screen. These lavish adaptations demand to be taken seriously, for they draw upon an epic fairy tale that addresses the ravages of war experienced by Tolkien himself. It is, therefore, not by chance that Jackson’s three films shed light on the perils of war in our contemporary conflicted world.

In addition to films produced for the big screen, fairy-tale films continue to be created for television, the internet, and iPods. America has at least three concurrent TV fairy-tale series: Once Upon a Time, Grimm, and Beauty and the Beast. 1 Germany has Sechs auf einen Streich and Märchenperlen, and important series have also appeared in Japan and South Korea. In the United Kingdom, Scotland, and Canada, the BBC Shoebox series appealed to large audiences. Significantly, these works are often accompanied by commercials and other peripherals that celebrate the magic qualities of fairy tales and urge us to change our lives by purchasing miraculous products.

Just as Georges Méliès revolutionized the fairy tale at the beginning of the twentieth century and was immediately followed by scores of other European and American filmmakers, numerous directors and artists are now revolutionizing the fairy-tale film, in part due to new technology that enhances cinematic special effects. But again, why such a revolution or tsunami now? Is this twenty-first century wave of fairy-tale films really so startling and new? (Consider the cinematic tsunami of fairy-tale films at the beginning of the twentieth century.) A look at the popularity of fairy-tale films in a historical context offers a more comprehensive perspective on the present.

Plays, operas, and vaudeville shows called féeries during the nineteenth century offered early signs that folktales and fairy tales would become a staple of storytelling in the modern mass media throughout the world. But fairy-tale films also stir our minds and emotions as part of our cultura...