![]()

Part One

The Dark Ages

![]()

Introduction

The introduction sets the scene for the chapters that follow. European civilization is defined not so much by geography as by cultural identities. The Romans conquered the cities on all the shores of the Mediterranean, establishing the sea as the cultural and economic focus of the Empire. Roman identity was dependent on empire, not geography. Unity on the shores of the Mediterranean was maintained by a quintessentially Roman belief that Roman law was based on nature, common to all peoples, and that all civilized men would therefore recognize it. Similarly, they held that the gods of different peoples were the same gods known by different names and therefore any pantheistic religion could be accommodated within the Roman infrastructure of a common religion. The Roman Empire, then, was centred on the unity of the Mediterranean, peoples and gods. Later chapters will trace the fragmentation of this unity, as the Empire came into contact with a religion that insisted upon one God and invaders who prized their racial identities more than an imperial common identity.

The civilization that we call European is not spread evenly over the continent of Europe, nor is it confined to Europe. Sometimes it has expanded and sometimes it has contracted. Kinglake came to the end of ‘wheel-going Europe’ and started his exploration of ‘the Splendour and the Havoc of the East’ in the Muslim quarter of Belgrade; that was in 1844.1 Further east there are lands that have once been European. The natives of Syria call modern Europeans, their houses, transport, clothes, and sanitation ‘franji’, because until the modern age they had known no European colonists since the crusaders or Franks. Even in Greece, Europeans are called Franks, since Greece was conquered by crusaders in the thirteenth century. On the southern shores of the Mediterranean, in Algeria, Tunisia, and Tripolitania, Europeans are called ‘Roumi’, because the previous exponents of European civilization were Romans. European civilization moves. Under the Greeks and the Romans it was based on the Mediterranean. By the sixteenth century it had shifted to the Atlantic seaboard, to the Netherlands, England, France, and Spain. In one sense, the history of medieval Europe is the history of this movement of civilization, northwards from the Mediterranean.

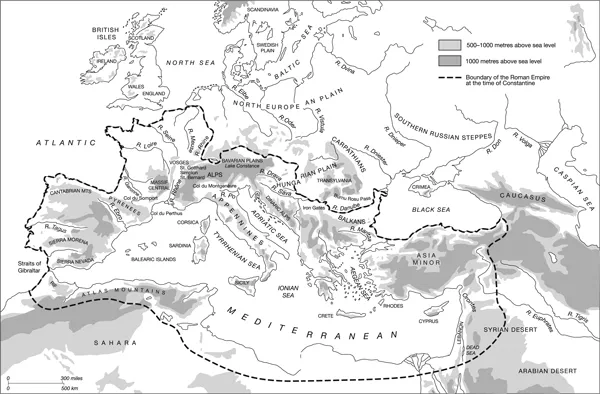

The Roman Empire was Mediterranean and embraced all its shores. It was not localized. Just as the second city of Greece was Alexandria, in Egypt, so the Emperor Constantine founded a ‘new Rome’ at Constantinople and called its people ‘Romans’. The Emperor Diocletian had built his palace at Split on the Dalmatian coast; one of the most famous schools of Roman law was at Beirut, in Lebanon, and the third largest Roman amphitheatre in the world is still to be seen in the Tunisian village of El Djem. Few of the great Romans of imperial times were of Roman stock. The Emperor Trajan was a Spaniard; Septimius Severus was a native of Leptis Magna in Tripolitania. Most significant of all was St Paul; his parents were Jews, but he was a Roman citizen because he had been born in the Greek city of Tarsus, which was on the coast of Asia Minor and was capital of the Roman province of Cilicia. He died at Rome, after he had undertaken missionary journeys over the greater part of the eastern Mediterranean.

The Mediterranean was not only the centre of the Roman Empire; it was what made the Empire possible. The magnificence of Roman roads is apt to make us think that Rome was primarily a land-power and to make us forget that Rome could not defeat Carthage until she was a sea-power. Rome depended on the sea. The corn for her bread came from Sicily and Egypt, and an outbreak of piracy in the middle sea could endanger her very existence.

Before the age of railways, motor-cars, and aeroplanes, all great civilizations depended on water-transport. The earliest civilizations grew up on rivers, where the hazards of navigation seemed less terrifying than on sea. For civilization depends on cities where men are spared the trouble of growing their own food and can devote their lives to specialized trades or arts; cities can only obtain their material needs by trading; trading requires transport; and transport is far more difficult over land than over water. To transport goods overland one needs roads and bridges, relays of horses and carts, and stopping-places where both man and beast can find food and rest in peace; it requires stupendous organization. To travel over water one needs nothing more than a boat.

In a boat, one can sail down the Nile and into the Mediterranean, the paradise of early sailors. It was neither too big nor too little. It was big enough to contain the marvels of the world, the golden apples of the Hesperides, the cave of Cumae and the pillars of Hercules; and yet it was small enough for the fearful mariner never to be far from sight of land. It invited exploration. The Greeks nosed their way along its shores in search of new lands and new markets, founding cities as they went, as at Cyrene on the African shore, or as at Naples (Nεάπoλις = the new city) in southern Italy where their cities became known as Magna Graecia. In Spain they founded the great market of Emporion and the city of Hemeroskopeion (‘the watch-tower of the day’). Nor were the Greeks alone. Phoenicians from Tyre had founded Carthage, and Carthaginians founded Cadiz. Exploration and trading went hand in hand. Trading led to cities and cities to civilization.

The Romans conquered the cities and the civilization, with the Mediterranean. They made an Empire out of the economic unit that existed already, and called the Mediterranean ‘our sea’, mare nostrum. They then set about defending it, for the sea was vulnerable from the land. Any invader who marched overland and conquered a portion of its shore, could build a fleet and disrupt the economic unity on which the Empire depended. Fortunately, the Mediterranean had natural defences on three sides. On the west and on the south were the Atlantic and the Sahara, both equally impassable. On the east, the Syrian desert formed a barrier against the Persians except at its northern extremity which was defended by the fortress of Nisibis. The weak frontier was on the north. If the Romans had only had to defend Italy, they could have made the Alps their frontier; but they had to defend the whole of the north Mediterranean shore. To protect the shores of Greece and Dalmatia they advanced to the Danube which they made a frontier against the Goths. To protect their province on the Mediterranean coast of Gaul, they advanced into northern Gaul; to secure northern Gaul they occupied Britain and advanced eastwards to the Rhine. Augustus decided that the advance should go no farther, and in consequence the northern frontier of the Empire followed the lines of the Rhine and Danube with only a small extension to the east in the region of the Neckar. A longer frontier could not have been devised. To garrison it, the Romans recruited Syrians, Armenians, Dalmatians, Spaniards, and even German auxiliaries. The frontier was the military centre of the Empire, for its purpose was not just the defence of Gaul or Illyricum, but of the whole Mediterranean. The Romans knew that once a rival power reached the shores of ‘their’ sea, it could shatter their economy and so bring an end to their Empire and their civilization.

The fact that Mediterranean civilization depended on the unity of that sea made it vulnerable from within as well as from without. It was essential to keep the Mediterranean peoples at peace with one another. It was the triumph of the Romans that they discovered how to do this with the least possible military effort. They knew that all the Mediterranean peoples had a common interest in the commerce of their sea, and they believed in men. They believed that all men had by nature an instinctive knowledge of what was right and what was wrong, and they believed that it was possible to frame laws in accordance with the standard of nature. They distinguished between custom which was of no more than local significance, and law which appertained to justice and was consequently of universal significance. They would have found the greatest difficulty in understanding the way in which we now think it natural for different civilized states to have different laws. Of course they did not expect all men to share their law at once, but they did expect all civilized men to share it. Roman law was aiming at absolute justice as ordained by nature, and men whose reason was educated would recognize it naturally. For centuries their confidence was justified; but Roman civilization was to be shaken when barbarian invaders claimed that their own laws were particular to themselves, since they were not founded on nature and reason, but on the dictates of their own divine ancestors.

It always has been that different races find self-expression in their religion as well as in their laws. But the Romans were convinced of the common humanity of all men, and just as they postulated a jus gentium, or law that was common to all peoples, so they postulated that there must be a common religion. They thought that, just as there were different languages with different words for the same object, so the differences between the gods of different peoples were differences only of names. They identified Zeus with Jupiter, Baal with Saturn, and the Celtic Mapon with Apollo. Julius Caesar reported that the Gauls paid most deference to Mercury, and after him to Apollo, Jupiter, and Minerva, ‘and about them their ideas correspond fairly closely with those current among the rest of mankind’. The statement shows a magnificent belief in the universal humanity of man, since it implied that even barbarians knew by instinct something of the truth discovered by civilized man. But the belief depended on pantheism. There had to be many recognized gods if all the gods of the barbarians were to be found equivalents in the Roman pantheon; and any new gods had to be content to take their place alongside deities that were already numerous. What could not be tolerated was a religion that claimed to have a monopoly of truth – that claimed not only that it was right, but that all other religions were wrong. Just as the Roman Empire embraced all Mediterranean peoples and gave them Latin names, so Roman religion embraced all gods and required that they also should observe the pax Romana.

The structure of the Roman Empire was based on the unity of the Mediterranean, its peoples, and its gods. In the following chapters we will see how that unity was broken. It was first cracked by the claim of the Christian Church to be the guardian of absolute truth, because that claim made religious compromise impossible. It was further cracked by the determination of barbarian invaders to prefer the law of their ancestors to the law of reason, since that preference implied the superiority of loyalty to one’s race over loyalty to the civilized world. It was shattered when traders lost the freedom of the sea. When that happened, the greater part of Europe reverted to an agricultural economy in which there was no place for the cities that made men civilized.

1 A. W. Kinglake (1809–91) was a journalist and historian of the Crimean War. His Eothen (London, 1844), referred to here, is a highly entertaining account of his travels in the Ottoman Empire. [R.I.M.]

![]()

Chapter 1

Constantine the Great: the New Rome and Christianity

Beginning with Constantine’s acquisition of imperial power and his conversion to Christianity, this chapter introduces a key theme of this book, namely the relationship between Church and State. Constantine’s foundation of Constantinople – ‘a new Rome’ – gave the Roman Empire a defensible stronghold in the East, whose strategic location allowed control of the eastern Mediterranean. Although his public expressions of power cannily appealed to pagan and Christian alike, Constantine attributed his political success to Christ and converted to what was essentially a minority religion (although he was not baptized until he was on his deathbed). He felt compelled to intervene personally to create unity within the Christian Church. To that end, he summoned the first general council of the Church, at Nicaea, and, moreover, presided over it. Constantine’s intervention in Church affairs raised fundamental questions as to where the boundaries between imperial and ecclesiastical concerns should lie.

Chronology

306 | Constantine the Great proclaimed Caesar, responsible for Gaul and Britain |

312 | Battle of Milvian Bridge; Constantine master of Rome and the West Empire |

316 | Constantine condemns the Donatists as heretics |

324 | Constantine sole emperor of the East and West |

325 | foundation of Constantinople Constantine calls and presides over the Council of Nicaea |

326 | Constantine has his wife and son killed |

336 | death of Arius |

337 | death of Constantine |

1204 | fall of Constantinople to the Crusaders |

1453 | fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks |

Constantine the Great was proclaimed Caesar by the imperial troops at York on the death of his father in 306. At that date the Roman Empire was ruled by two emperors (augusti) and two junior colleagues (caesars), and the Christian religion was proscribed. Constantine’s sphere was Gaul and Britain, but he set out to conquer the whole Empire for himself, to have the Christians as his allies, and even to become a Christian himself. By 312 he had defeated one of ...