1

THE STUDY OF CLOSE RELATIONSHIPS IN THE EARLY 21ST CENTURY

Relationship is a pervading and changing mystery . . . brutal or lovely, the mystery waits for people wherever they go, whatever extreme they run to.

—Eudora Welty in The Quotable Woman (1991, p. 44)

IT IS THE EARLY 21ST CENTURY AND THE DIVORCE DILEMMA CONTINUES

As the 2000 U.S. Presidential election neared, a dialogue was occurring among candidates and the general public about the unabated high divorce rate in this country and how the divorce rate affects the American family. For over 3 decades, the divorce rate has been between 40% and 50% of all new marriages. All parts of the United States appear to have experienced significant divorce rates during this period. Even areas with major religious affiliations among the general populace have been affected. A UP headline in 1999 (November 13, 1999, reported in Iowa City Press-Citizen) said, “Bible Belt States Struggle with Divorce.” This article noted that although the overall rate per 1,000 people was 4.2 divorces, the rate was 6.4 in Tennessee, 6.1 in Arkansas, and 6.0 in Alabama and Oklahoma. In contrast, Connecticut, Massachusetts, and New York had rates of less than 3.0. Why might these differential rates be occurring at the start of the 21st century?

One ironical answer is that the so-called Bible Belt states are dominated by protestant churches that are not as active as states dominated by the Catholic Church, which has had a significant premarital counseling program for some time. It is possible that “fundamentalist” churchgoers are more exposed to what the AP article suggested was a “fairytale conception of marriage,” that is not altered by any of the preparations done by the couple in getting ready for marriage. As we see later in this chapter, the idea of premarital counseling has taken hold, especially among young couples and among politicians in state capitols, as a possible way of redressing the high divorce rate.

In thinking about the complexities of human close relationships, the divorce dilemma is similar to other riddles in that many factors very likely are involved. Simple answers should be mistrusted. The divorce rate in these Bible Belt states may be influenced by the people’s adopting the biblical view that the man is head of the household (e.g., the Southern Baptist Church asserted this position in its constitution in 1998). Yet, the close relationship literature suggests that egalitarian relationships in which both partners are treated as equals yields much more satisfying, and most likely long-lasting, relationships. Further, as the Associated Press article noted, cohabiting before marriage is more criticized in Bible Belt states. If, as many people suggest, such a step before marriage provides a good trial-run for marriage, this factor may mitigate against couples surviving for long when they plunge into marriage without enough experience with one another. Even these explanations are highly speculative. Perhaps all we can do with such complex phenomena is be open to careful consideration of the multiple explanations that may be advanced.

HISTORICAL NOTES

The teaching of classes on close relationships did not begin on a widespread basis until the late 1970s. The reason that close relationships were not a part of psychology curriculum before that period was that the area of work, in psychology, did not develop in earnest until the late 1970s and early 1980s. It had not developed prior to that point because the discipline of psychology, ironically enough, demurred in viewing this topic as sufficiently scientific; that all changed in the late 1970s with work designed to make the case for a science of close relationships (CRs) and to develop scholarly organizations and journals specifically focusing on relationships. Now, there are several specialized journals and two large international, interdisciplinary organizations that hold annual relationship conferences.

In a very selective way, Table 1.1 documents some of the developments in this interdisciplinary field.

TABLE 1.1

General Sketch of Important Developments in

The Interdisciplinary Study of Close Relationships

- Family Sociology, developing in 1930s, emphasizing demographic variables (e.g., study of success of marriage and divorce trends, Burgess & Cottrell, 1939)

- Early researchers and contributions in social psychology and sociology in 1950s, 1960s, 1970s, and early 1980s in studying close relationships phenomena:

- Leon Festinger, study of attraction to others (e.g., Festinger, 1953)

- Elliot Aronson and Judson Mills study of liking for others (e.g., Aronson & Mills, 1959)

- Carl Backman and Paul Secord, study of interpersonal attraction (e.g., Backman & Secord, 1959)

- Donn Byrne, study of attitudes, personality, and attraction (e.g., Byrne, 1961)

- George Levinger, study of marriage via archival records (e.g., Levinger, 1964)

- Bernard Murstein, study of marital choice (1970)

- Keith Davis, study of romantic love (e.g., Kerckhoff & Davis, 1962)

- Elaine (Walster) Hatfield, study of romantic love and determinants of interpersonal attraction (e.g., Hatfield & Rapson, 1993; Walster, 1965)

- Clyde Hendrick, study of attitude similarity and attraction (e.g., Hendrick & Page, 1970)

- Irwin Altman and Dalmus Taylor, study of self-disclosure (e.g., Altman & Taylor, 1973)

- Zick Rubin, Letitia Anne Peplau, and Charles Hill, study of liking and loving (e.g., Hill, Rubin, & Peplau, 1976; Rubin, 1973)

- Harold Raush, study of communication in marriage (e.g., Raush, Barry, Hertel, & Swain, 1974)

- Jessie Bernard, study of marriage (e.g., 1972, 1982)

- Robert Weiss study of marital separtion (e.g., Weiss, 1975)

- Ellen Berscheid, study of interpersonal attraction (e.g., Berscheid & Walster, 1978)

- Steve Duck, study of acquaintance and friendship (e.g., Duck, 1973) and organizational efforts in developing an association of scholars for studying close relationships (e.g., Gilmour & Duck, 1986)

- Ted Huston, study of social exchange in developing relationships and of transitions in relationships (e.g., Burgess & Huston, 1979)

- Philip Blumstein and Pepper Schwartz, study of relationship processes in different types of couples (e.g., Blumstein & Schwartz, 1983)

- Harold Kelley and colleagues, study of interdependence in close relationships (Kelley, 1979, Kelley, Berscheid, Christensen, Harvey et al., 1983)

- Early organizational developments

- Madison, Wisconsin Conference in 1982 organized by Robin Gilmour and Steve Duck

- Subsequent conferences every year, many with locations outside the United States

- Development of Journal of Personal and Social Relationships (by Steve Duck in 1983), later became official journal of International Network on Personal Relationships (approximately 500 members at beginning of the 21st century)

- Development in 1994 of Personal Relationships, as official journal of International Society for the Study of Personal Relationships (also with approximately 500 members at beginning of the 21st century)

- 2001 beginning of merger between the two international organizations for the study of close, personal relationships and merged meetings of the organizations (with merged meeting in Prescott, Arizona)

- Other major developments

- Development of interpersonal relations component of the discipline of communication studies in the 1980s, with close relationships a principal research focus

- Continued development of field of family studies, often in university departments entitled “human development and family studies,” also with close relationships as a main line of work; related development in this field of accredited programs to train therapists in marriage and family therapy

- Continuing development of close relationships as a primary research topic in social and clinical psychology (and to a lesser degree in developmental and counseling psychology); social psychology’s commitment is reflected in probably 500–1,000 social psychologists currently pursuing this topic and the topic’s currency at conventions (including special sessions at the prestigious Society of Experimental Social Psychology meetings)

- 1978, approximate first date undergraduate course explicitly focusing on close relationships taught at a North American university (Berscheid, 1997)

Table 1.1 reflects only a smattering of the people and events leading to the burgeoning interdisciplinary field of close relationships. It can be seen from this table that many people (including many who were not listed) contributed to this development. The field was quite embryonic through the mid-1970s, but it took off with considerable vigor by the early to mid-1980s.

We have taught a relationship course (both at the undergraduate and graduate levels) since the late 1970s (JH) and early 1980s (AW). The course has had a large following at a number of universities where we have taught. We are convinced that this relationship course has had such a strong following over the years because relationships dynamics are so vital a part of the lives of people in their 20s—not to say they are not vital in all of our lives.

THE TOWERING IMPORTANCE OF CLOSE RELATIONSHIPS

According to a recent Gallup survey (USA Today “snapshot” 4-14-98) of young adults’ (ages 18–34) priorities, 83% rated a close-knit family as their highest priority—even more so than a career (rated highest by 68%). Also, for all adults, 64% say that “relationships with loved ones always are on their minds” (with “stability/security” rated second at 51%—USA Today “snapshot,” 1-6-98). A recent poll of the 16 to 21 age group in the United Kingdom revealed that “to be happily married with children” was the most popular aspiration, coming out ahead of a successful business career (The Economist, January, 1999, p. 15).

Further evidence about the impact of close relationships on health is rapidly accumulating. Myers and Diener (1995) report that people look to family and close relationships for the main sources of their happiness. Berkman, Leo-Summers, and Horwitz (1992) showed that the chances of survival for more than 1 year after a heart attack are more than twice as high among men and women at mid-life and beyond when the men and women are emotionally supported by two or more people. Kiecolt-Glaser and associates (1987) found that the immune systems of happily married persons fend off infections more readily than do the immune systems of unhappily married persons. More generally, Campbell, Converse, and Rodgers (1976) reported that people’s feelings about their relationships have a larger impact on their overall satisfaction with their lives than do their job, income, community, or even physical health. As we will see in the dissolution chapter (chapter 10), the end of a close relationship can be quite destructive to a person’s psychological and physical health.

DEFINING A CLOSE RELATIONSHIP

How do we define a CR? One definition of close relationship that will be invaluable to our attempt to have a working definition was provided by a team of psychologists led by Harold Kelley who wrote one of the first textbooks on close relationships that emphasized a scientific orientation to the study of relationships. Kelley et al. (1983) defined a close relationship as: “. . . one of strong, frequent, and diverse interdependence [between two people] that lasts over a considerable period of time” (p. 38). Kelley et al. conceived interdependence as the extent to which two people’s lives are closely intertwined, in terms of their behavior toward one another and thoughts and feelings about one another (see also Berscheid, Snyder, and Omoto, 1989). They also viewed the time factor as involving months or years rather than days.

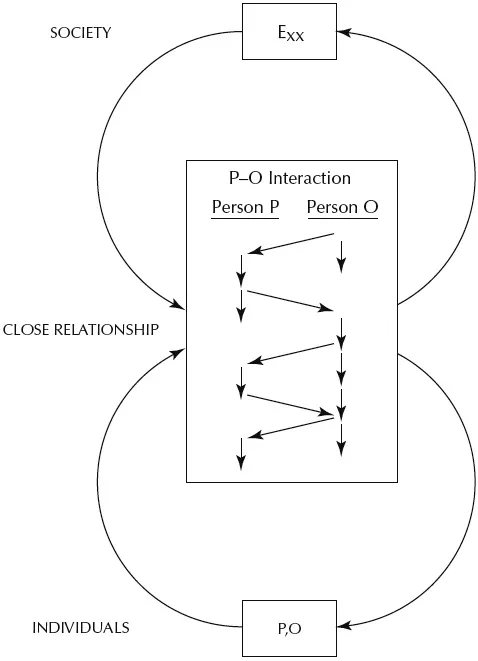

Interdependence is represented in Figure 1.1 from Kelley et al. (1983). The recursive, feedback loop of forces thought to be most important in an interdependent bonding are evident in this figure.

It can be seen that in the middle box, Person P and Person O are involved in a series of interactions over time (arrows going back and forth reflect behavior such as verbal statements and nonverbal smiles and frowns; arrows going down reflect time). Outward arrows from the P × O box show how the couple affects the external environment (E soc) and how their interactions form a unit P,O that is different from each of them. This latter effect is quite interesting. The couple becomes the third part of the relationship (P, O, and the P–O unit). It is often said that each love relationship involves a particular type of coupling. This figure suggests that coupling derives from the particular interactions of the two people. Further, this figure shows an arrow going from the P,O unit back to the box of P times O interaction, (P × O) reflecting the influence of the particular nature of the couple on interactions.

Finally, it should be noted from Figure 1.1 that outside events in the environment affect the P × O coupling. There are many examples of this phenomenon. During World War II, many marriages between American male soldiers and English women occurred when the soldiers spent sometimes up to a year in England in preparation for the Normandy invasion in 1944. Similarly, after hurricane Andrew devastated South Florida in the early 1990s, social service officials noted a 75% jump in divorces in the area most affected. Presumably, the hurricane introduced great stresses to couples’ relationships that already were troubled; the added stresses proved to be too much.

The psychotherapist John Welwood (1990) defines a close relationship as “. . . rather than being just a form of togetherness, a ceaseless flowing back and forth between joining and separating” (p. 117). The “pulling” part frequently is one or both partner’s work at autonomy. Baxter and Montgomery (1996) more explicitly address the dialectic nature of relationships (e.g., our co-occurring needs for autonomy and dependency). The yin and yang of a close relationship is how to achieve balance between the couple’s need for being united on many critical dimensions and the need of the individual member of the couple to achieve autonomy.

A simpler approach to defining a close relationship is a relationship that has extended over some period of time and involves a mutual understanding of closeness and mutual behavior that is seen by the couple as indicative of closeness. According to this definition, a number of deductions about what CRs are and are not may be made. For example, so-called “empty shell” and “convenience marriages” in which neither party may define the relationship as close do not constitute CR. What are some other major implications of this definition?

Although the couple may use the term “love” or some other term for “closeness,” the key is that they each believe it exists to some degree between them and that they each believe that behavior consistent with that sentiment occurs. A close relationship is a process. It flows along, not unlike a river, with varying degrees of intensity and various bends and crooks in its path. Although it may run dry, or terminate, the path that the relationship forged likely will continue, indefinitely, to have consequence in the minds and actions of its participants. Does it matter if the members of a couple feel different degrees of closeness or exhibit different degrees of behavior consistent with closeness? No. Most couples likely will show variability within the relationship and over time in their feelings and behavior. They need to be satisfied with the differences, or as is described in chapter 6 on maintenance, work toward resolutions to differences that are problematic.

FIG. 1.1 Interdependence model.

From Close Relationships by Harold H. Kelley, et. al. © 1983 by W. H. Freeman and Company.

Will a close relationship exist if one party feels close and behaves as if he or she is close, while the second party does neither? No. The feeling and behavior must be mutual. Many people have imaginary lovers who never reciprocate. If there is no reciprocation, there is no close relationship.

What about biological/blood relationships? Are they always close? No. Only if the feeling and behavior mutually support closeness. What about friendships? The same. Some may be close relationships; some are not.

What about the length factor? Is it not possible that some “less extensive” periods of time will be propitious for the formation of a close relationship? Yes. But the average period for such a development will be “more extended,” or in the time frame of months or years as Kelley et al. (1983) contend. Certainly, a sexual relationship may be started on the average in a shorter period, but a sexual relationship does not necessarily make a close relationship. One may live only a short period after starting what clearly involves mutual closeness with a partner. We must say that such a person did indeed have a close relationship and that it unfortunately could not be extensive in nature. As we all age and sometimes take on new partners in older ages, there may be only a few weeks or months duration to some relationships. Our definition must entertain enough flexibility to consider the context of relating, and in such cases, close relationships clearly do exist.

What about change over time? Is it not possible that mutuality in feeling and behavior may ebb and flow over a long relationship such that at some points, one or both parties may be essentially acting as if no close relationship exists. Yes. That is a common occurrence. They may or may not come back together, and how fatal the downward spiral is may be determined by many factors including perceived betrayal (as when one is involved in an affair that is found out about by the other, who perceives such an act as fatal in nature).

What if one party vacillates greatly between feeling and expressions of closeness and feelings and messages that paint a picture of ambivalence (“I love you, but I don’t know if I want you in my life.”); while the other party generally is consistent in his o...