![]()

1

INTRODUCTION

Developing Expertise and Learning to See

Technical communication, as an academic discipline and as a field of practice, has grappled with questions of expertise for centuries. Most historical accounts of the profession, such as Connors’s (1982), Longo’s (2000), and Kynell-Hunt and Savage’s (2003), make visible our persistent struggles over authority, legitimacy, and the right to claim expertise. Perhaps this focus on disputes of power is not surprising; after all, claims of expertise, as Hartelius (2010) reminds us, entail rhetorical contests over “ownership and legitimacy” between “autonomous” (or genuine) expertise and “attributed” expertise (a type that gains its credibility from others’ recognition) (3–4). In technical and professional communication (TPC), questions of expertise—autonomous or attributed—are structured by what Geisler (1994) describes as a “dual problem space framework” that divides expertise into two distinct components: a content domain and a rhetorical process domain (82). Various stakeholders in the academy and the professions use this division to grant expertise to some while withholding it from others (89). In TPC, those with more social, political, and economic capital apply these alleged distinctions between content and form as well as between subject-matter and rhetoric to identify those who do the supposedly real work of science (scientists) and those who merely write it up (writers) (Longo 2000). Following this bifurcated approach, we inevitably (perhaps inadvertently) split knowledge from know-how, or what Ryle (1949) famously termed “knowing that” and “knowing what” (28). In adhering to this binary that Carter (2007) calls “conceptual knowledge” versus “process knowledge” (387), we separate knowledge of a domain from the ability to communicate that knowledge.

While some people do possess greater expertise in areas of content and some in areas of communication, we should not view communicative expertise, or the expertise involved in communication, as easily divisible from what I call technical expertise, or the specialized knowledge that professionals use in technical domains, including science, medicine, engineering, math, architecture, and fields intimately connected with them, like TPC. As Geisler (1994) illustrates, communicative expertise requires not only subject-matter knowledge and rhetorical skills, but also involves ways of thinking and problem solving coupled with the ability to understand the rhetorical and social aspects of communication (92). Similarly, Tardy’s (2009) exploration of communicative expertise complicates these dichotomies by demonstrating how formal, process, and rhetorical knowledge of a content domain depend on both knowledge and know-how. This dualistic model stems, I contend, from a view of knowledge as an object to possess, a focus on traditional written texts, and a disembodied approach to meaning making in general. When we consider expertise a form of activity, as Regli (1999) encourages us to do, we find that expertise, particularly technical expertise, cuts across these dichotomies. Being an expert involves all of these allegedly disparate areas: knowledge and know-how, communicative abilities and subject-matter knowledge, even autonomous and attributed expertise. Technical expertise, as I demonstrate, is not about having and not having, but about seeing and doing—specifically, using the body’s capabilities to develop and enact knowledge and know-how. Technical expertise, as such, is a type of trained vision we acquire through embodied practice.

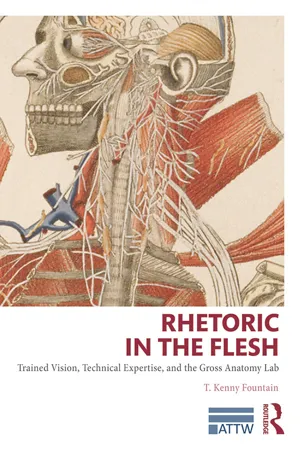

Rhetoric in the Flesh is a book about expertise and vision; more precisely, it is about learning to see in technical domains. A few conceptual questions motivate my inquiry: How do newcomers to a professional group come to see according to the practices, values, and beliefs of that community? And what part do images and visual displays play? To move beyond an exclusive focus on conventional word-based documents, Rhetoric in the Flesh attends to the ways visual images and objects participate in processes of education and socialization. Specifically, I describe how we acquire technical and communicative expertise by learning to see as a member of a particular group. Through an ethnographic analysis of one medical school’s gross anatomy program, I explore how participants develop knowledge and expertise in a scientific field, in this case, cadaver-based anatomy. In telling this story of images and expertise, I explore the mutually structuring relationship between visual displays and bodies in the gross lab, and I do so in order to interrogate the rhetorical function of images and objects in the production of medical knowledge and the development of medical professionals.

Yet, images are not the only means of producing this skilled perspective. Participants in this domain of technical work also learn to see and recognize the anatomical body through rhetorical discourses that introduce students to the values, perspectives, and beliefs of medicine. The development of anatomical knowledge and know-how, including a medical professional’s clinical detachment, coincides with the skillful use and suasory force of visual and rhetorical displays of evidence and values, or what I describe as apodeictic and epideictic demonstrations. By focusing on the contemporary anatomy lab as an assemblage of multimodal displays, medical and institutional discourses, and rhetorical and embodied practices, I explain how over time participants develop a perspective that shapes how they view and even respond to the human body. Thus, as I demonstrate, technical experience and professional dispositions are, in a significant way, rhetorically trained. Furthermore, participants develop this expertise, this trained perspective, by learning to engage bodily with the displays, objects, and discourses of this technical space.

Expertise and Trained Vision

Geisler (1994) defines expertise as a type of knowledge that “goes beyond everyday understanding,” and which a person acquires through “specialized training and practice” (53). She contends that expertise is transmitted most often in formal educational settings through “interactions over texts” (54). Literate practices, namely reading and composing written texts, are crucial to gaining, communicating, and transferring expertise (92). Most TPC studies of expertise acquisition have focused on these conventional documents, such as reports, manuals, and the academic and professional writing of novices. This concern with the written word is unsurprising given the cultural power and semiotic complexity of writing particular to a field that began with “technical writers” and “teachers of technical writing” (Connors 1982; Kynell and Tebeaux 2009). However, as research has shown, knowledge production and expertise transmission in TPC are not exclusively instantiated through word-dominant texts. As Sauer (2003) and Johnson (2006) demonstrate, nonwritten modes, from gestural to oral communication, often convey knowledge and know-how necessary to the work of science and technology.

One prime example of a non-word-dominant mode of TPC that has received increasing attention is the image-based text. In scientific, medical, and technical professions, images play a major role in constructing expertise, making arguments, and transforming the perceptions of audiences both inside and outside of science (Donnell 2005; Gross, Harmon, and Reidy 2002). The production, interpretation, communication, and distribution of scientific knowledge require a host of visual representations deployed or, as Latour (1990) asserts, “mobilized” to make and communicate knowledge claims (40). These scientific visual displays are evidentiary artifacts generated to represent, contain, and shape research findings or observable phenomena (26). Participants in scientific, medical, and technical contexts accomplish their work and produce relevant phenomena through processes of verbal and visual inscription, activities that transform “material substance into a figure or diagram” that participants then use to back up or refute statements, hypotheses, and claims (Latour and Woolgar [1979] 1986, 51). In no small part, these displays constitute scientific knowledge by making it visible.

With advances in technology, visual displays—and even documents once understood as primarily word based—are increasingly multimodal objects that communicate through various channels, discourses, and media (Kress and van Leeuwen 2001, 2–4). As a result, many researchers have criticized as unhelpful and inaccurate once-rigid distinctions between visual and verbal texts (Kostelnick and Hassett 2003; Kress and van Leeuwen 2001; Wysocki 2004). In scientific and technical contexts, displays of all kinds are multimodal objects that signify through a combination of visual, verbal, spatial, and even physical or material modes. These multimodal displays of scientific research—such as graphs, charts, photos, and 3-D representational objects—carry a persuasive and ontological force that influences the formation and dissemination of scientific arguments, a force that shapes how scientists and nonscientists alike view these objects and phenomena. Multimodal displays, then, not only communicate knowledge and know-how; they also train participants to view this knowledge and the objects of their profession in a certain light. As such, technical expertise—an advanced mastery of the knowledge and know-how of a technical domain—involves learning to see and use objects, tools, and discourses according to the authorized practices of a particular group.

In this way, the visual practices of a community enact a type of socialization, developing in participants what Goodwin (1994) describes as “professional vision,” or “socially organized ways of seeing.” (606) This socialization is at once a philosophical worldview, a disciplinary framework, and a visual orientation allowing community members to see social phenomena (tools and objects rendered by a social group) according to the logic of that profession. For example, an archeologist-in-training develops the professional vision of her field by learning to make scientifically relevant observations in “a patch of dirt” by reading it through the interpretative frame provided by visual displays, such as the Munsell color chart (606). By learning how to use multimodal displays as interpretative frames, or what Goodwin (2000) terms an “architecture for perception,” participants come to see the objects of their environment according to the culture of that group (34). To develop this trained perspective, participants must learn to use and read these displays correctly, a skill they learn through immersion and socialization into the literate, visual, discursive, and embodied practices of a group (Goodwin 2000).

Scientific and technical practices produce multimodal displays and objects plus ways of viewing those objects that shape the perceptions and perspectives of participants. This trained perspective, for Grasseni (2007), is the result of a participant’s embodied interactions with a “richly textured environment” of objects, bodies, and images (207). In her ethnographic study of the training of cattle breeders, Grasseni redefines vision as “the capacities and capabilities” derived through apprenticeship and training in a particular community of practice (215). That is, “skilled vision” is cultivated when we gain the ability to see by way of the interpretative frames and objects situated in “an ecology of practice” (Grasseni 2004, 41). Through the development of this skilled perspective, a person learns to “see as” a member of a group in a way that makes expertise material and visible to members and nonmembers alike (Grasseni 2007, 7). Skilled vision not only shapes and communicates meaning; it also fundamentally makes possible the meanings, attitudes, and practices of a group (5).

Situated practice, then, not only produces knowledge and know-how, but also ways of viewing that knowledge and the objects and discourses of that knowledge, ways of being in the world that shape the lived experience of participants. This “trained vision,” as I call it, is the organization of perception through the interplay of multimodal displays and objects, interpretative frameworks, and the situated activities that create and deploy them. Trained vision, which we learn through formal training and informal socialization, originates with the material practices of a group and our embodied participation in those practices. We develop expertise, technical or otherwise, not just through socialization into a community’s discourses, genres, documents, multimodal displays, and objects. Instead, we develop expertise when we develop the skilled capacities necessary to use the discourses and objects, the displays and documents, according to the explicit and tacit rules of that community. Acquiring these capacities with objects and discourses involves the acquisition of particular ways of seeing, thinking, and being in the world. This trained vision both coincides and coconstructs expertise. Thus, the literate activities and bodily capacities that result in technical expertise originate with our embodied interactions with the discourses and multimodal objects of a community.

Clearly then, expertise involves more than learning the knowledge of a group; it involves learning to perform tasks as a member of that group as well as gaining the social role that allows one to perform those tasks. The more I learn to perform the practices of a domain, the more mastery I attain. Becoming a scientist, doctor, engineer, or a technical communicator requires a person learn content knowledge and rhetorical knowledge, but not always as separate forms of knowledge. Through embodied socialization into the language, genres, discourses, documents, displays, and practices of a technical domain, we develop technical expertise. To learn these ways of knowing, seeing, and being, we must immerse ourselves in practices of that group. Only then can we acquire the knowledge and develop the skills and dispositions of that community. Learning to see means learning to recognize, appreciate, and understand the images and objects of our discipline; it also means learning to share the same values and convictions prized by that discipline.

The Focus of the Book

The anatomy lab offers a clear vantage point to view how multimodal objects, together with rhetorical discourses, form the trained vision of technical expertise. My analysis of these embodied and rhetorical processes develops from my ethnographic observations and immersion in one American medical school’s human anatomy program, specifically, the two gross anatomy courses that composed that program: (1) ANAT 600, a dissection lab for first-year medical and dental students using fresh cadavers; and (2) ANAT 303, an undergraduate course using prosected (or previously dissected) cadavers. Through an analysis of field notes, interviews, course material, and photographic documentation I collected during my fieldwork, I demonstrate how anatomy education is a social, embodied, and deeply rhetorical endeavor. That is, these gross anatomy labs use two types of rhetorical demonstrations: (1) multimodal displays used to exhibit anatomical knowledge; and (2) institutional discourses used to represent and impart knowledge and, more importantly, to inculcate the values of anatomical study and medical science. These demonstrations of evidence and values correspond broadly to ancient rhetorical notions of apodeixis (displays of proof) and epideixis (displays of cultural values). Together, the apodeictic displays, in the form of multimodal objects and rhetorical demonstrations, and the epideictic verbal discourses and narratives induce in participants a trained vision that shapes how they view the anatomical body of medicine and the lived body of human experience.

This trained vision is the result of participants’ bodily encounters with multimodal objects—such as images, photographs, x-rays, and cadavers—and their repeated exposure to the epideictic discourses and processes that laud cadavers as crucial to learning and eulogize cadaveric donors as altruistic gift givers. To learn, teach, and communicate anatomical knowledge, participants must recognize the anatomical body in the multimodal displays. They accomplish such recognition by learning how to view, touch, move, and manipulate the bodies of the lab—the nonhuman displays that represent anatomy and those living and dead bodies that present anatomical structures. Thus, the multimodal displays and embodied practices of this medical setting facilitate learning and technical expertise while shaping participants’ perceptions of the body. Also, the rhetorical discourses that influence how participants work with and feel about these objects fundamentally shape participants’ abilities to engage in the embodied activities of demonstrating, observing, and dissecting. By investigating the role that discourses, multimodal displays, and human bodies play in the training and socialization of medical students, I explicate how these displays, discourses, documents, and practices lead to the trained vision necessary for expertise. I do so by illustrating how embodiment and bodily practices are paramount to any configuration of rhetorical action and TPC.

By explicating the embodied practices and nonscientific rhetorics that enact the trained vision of medical professionals, Rhetoric in the Flesh contributes to our knowledge of how learning to see—in any technical field—develops through formal training and informal socialization. Over time, a participant develops trained vision through what I call the “embodied rhetorical actions” of a domain, actions that make possible all scientific, medical, and technical practice, knowledge, and expertise. As such, there can be no technical and professional communication without the embodied practices necessary to read, compose, and distribute rhetorical displays, documents, and discourses. Further, we can only acquire and communicate expertise through our embodied interactions with the rhetorical displays that constitute our domains of practice.

Training Vision in a Gross Anatomy Lab

Since the late middle ages, the study of cadaver-based anatomy has served as a primary introduction to anatomical knowledge and as the foundation of medical education—the rite through which students not only acquire seemingly authoritative knowledge of the body but also become practitioners of medicine (Carlino [1994] 1999; Park 2006). The practices of dissection, demonstration, and observation communicate this authoritative knowledge to those who seek to reveal the body’s supposed secrets. For centuries, the activities of cutting, presenting, and viewing human bodies have dominated medical education in America (Sappol 2002; Wells 2001), England (Richardson 2000b), and Europe (Carlino [1994] 1999; Cunningham 2010; French 1999; Klestinec 2011). As a contemporary medical discipline, human anatomy is primarily the study of the structure of the body (Moore and Dalley 2005). As the foundational language of medicine, anatomy is not just a list of parts to be identified but a complex knowledge system using mostly Latin and Greek terms, anatomical planes such as median, sagittal, coronal, and transverse, as well as spatial orientations of comparison and relation such as superficial and deep, medial and lateral, and posterior and anterior (Moore and Dalley 2005, 5–8).

But instead of simply observing and memorizing anatomical terms and structures relating to the whole of the human form, students must learn those structures systemically, learning individual parts as components of larger systems that work together to create the functioning human. For more than four centuries, students and teachers have used visual illustrations and other images to aid them in dissecting, identifying, teaching, and learning (Carlino [1994] 1999; van Dijck 2005). These displays depict anatomical knowledge through a complex network of multimodal objects—from dead and living human bodies, x-rays, CT (computed-tomographic) images, plastic models, and digital imaging, to images from atlases (bound collections of scientific images designed to train novices). Today, as it has been since the sixteenth century, students and even teaching assistants (TAs) learn anatomy primarily through their skillful interactions with these multimodal displays and the physical human bodies they represent. Take for example, the photograph in figure 1.1.

Though we cannot see them here, there are, of course, cadavers, either lying atop tanks that look like tables or tucked away inside them. What we do see are the first bodies students encounter, the 2-D and 3-D representations that cover the walls and whiteboards, the ones that rest on tables and countertops.

These photographs, x-rays, color illustrations, line drawings, and professionally produced posters, not to mention the cadavers, constitute the primary texts and displays of the course, the tools necessary for learning, teaching, and enacting the anatomical body. Through their bodily interactions with these displays, participants make anatomical knowledge discernable on and through these visuals. In the process, students and TAs develop a trained vision—in this case, an anatomical perspective—that shapes their perceptions of the human body, both the dead bod...