![]()

The developing world | PART I |

![]()

Third World or developing world? | CHAPTER 1 |

What is development?

The meaning that you attach to the term development depends on where you start from. It means different things to different people, even at its most mundane and practical level. For example, a resident of rural Senegal might see development as the availability of very basic services such as a reliable source of potable water; someone living in the suburbs of Greater Buenos Aires would expect rather more. Certainly both would associate the term with some sort of improvement in the quality of their lives. A concern with quality rather than quantity contrasts sharply with the traditional view of development measured simply as an increase in a country’s gross domestic product (GDP), now called gross national income (GNI).

Then ‘development’ was seen as making economic changes which would seek to counter the problem of global poverty, which was being addressed for the first time in the post-war era. Poverty was believed to be measurable in economic terms, simply as the amount by which per capita income fell short of the US level, and so was easily solvable by economic changes. Today development is a much more complex concept, involving consideration not only of the crude increase in production, but of the nature of that production and the range of social facilities which accompany it. It is this stress on quality rather than quantity which distinguishes ‘development’ from ‘growth’.

But this still does not answer the often-asked question of whether the concept is properly an economic or a political one. Development agendas change over time (see the discussion on poverty and basic needs in Chapter 3). A decisive response laying strong emphasis on political or economic aspects of development usually reflects strong attachment to a particular perspective. It would be hard to criticise the scope and range of the definition given by Michael Todaro:

Development must therefore be conceived of as a multidimensional process involving major changes in social structures, popular attitudes and national institutions, as well as the acceleration of economic growth, the reduction of inequality, and the eradication of poverty. Development, in its essence, must represent the whole gamut of change by which an entire social system, tuned to the diverse basic needs and desires of individuals and social groups within that system, moves away from a condition of life widely perceived as unsatisfactory toward a situation or condition of life regarded as materially and spiritually ‘better’. (Todaro 1994: 16)

At its simplest and most cogent the term may be best expressed as in the work of Amartya Sen (Sen 1981) as a reduction in vulnerability and as increased strength to counter problems consequent upon an enhancement of the options available. For Sen, development involves the increased freedom of the population. There is in this a validity that other definitions do not so adequately express, since income as measured by purchasing power gives freedom, but the freedom it gives also includes a capacity to meet a series of needs within society, for participation, health, education, etc.

Which are the developing countries?

Like most things in the social sciences, this is not as simple as it looks. The term developing countries is a very general term which may be applied to all except the advanced industrialised countries (AICs). That is to say, it includes countries designated by the World Bank and International Monetary Fund as low and middle-income countries (the Bank additionally divides the middle-income countries into upper and lower middle-income countries). Not the least of the problems with the term is that not all the ‘developing’ countries are in fact developing. We can divide them loosely into groups, though there is some overlap between these.

1. The very poorest (low income) countries, most though not all in Africa, which have failed to develop in terms of the quality of life of most of their population. Most have remained critically dependent on the export of a single raw material or crop (Ghana, Namibia). Others, like Afghanistan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Liberia or Sierra Leone, have been ravaged by civil war and will need massive support from abroad to rebuild their devastated infrastructure.

2. The large majority of lower and upper middle-income countries which despite their efforts remain relatively poor by world standards.

3. The oil (petroleum) producing countries which gain a high income from the depletion of their irreplaceable resources and are able to sustain a relatively high standard of living for their peoples, but which otherwise lack any of the basic requirements for sustained economic growth. Some, like the United Arab Emirates (UAE), are high-income countries.

4. The newly industrialised countries (NICs) or newly industrialising economies (NIEs), of which more later.

In recent years the term ‘developing countries’, fashionable in the 1950s, has been regaining popularity at the expense of its two more recent predecessors: the Third World and the South.

First World and Third World

During the Cold War the term ‘Third World’ gained acceptance quickly as a convenient term to denote all those countries which were neither ‘Western’ AICs, with well-developed free market economies, nor countries of the former Soviet bloc, with command economies.

Though Third World countries were developing countries in the economic sense, the reason was political: the three-way division of the world reflected the political dilemma facing the newly independent states in an era characterised by two power blocs. The earliest tentative moves towards the establishment of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), notably the Bandung Afro-Asian Solidarity Conference in 1955, included states on the basis of their independence not their ideological leanings. Cuba, despite its strong Cold War alliance with the former Soviet Union, became a leading member of the Non-Aligned Movement, as did Pakistan, despite its clear pro-Western orientation. But both could conveniently be grouped together with others as being part neither of the First World (the advanced industrial economies) nor the Second World (the command economies of the USSR, Eastern Europe and China).

During the Cold War, the ‘Third World’ became an arena for conflict, for two reasons. Despite the apparently overwhelming power of both the United States and the Soviet Union, each sought to influence the world balance of power by winning allies and friends among the uncommitted. Some, such as India, made a particular point of asserting their independence of either power and so made particularly desirable friends. Secondly, the nuclear stand-off made the prospect of war between the two superpowers so dangerous that the conflict between First and Second Worlds was played out by proxy in the Third - Korea, the Congo, Vietnam. Clandestine support to insurrectionary movements by both the Soviet Union and the United States added another zone of conflict.

South v North

Many developing countries resented the numerical suggestion of a ‘pecking order’, and for a time academic writers preferred to divide the world between the developed ‘North’ and the less-developed ‘South’. But the term ‘South’ needed to comprise the Americas as far north as Mexico (which is in North America); the whole of Africa; Asia apart from the former Soviet Union, China and Japan; and Indonesia, the Philippines and New Guinea but not Australia and New Zealand (cf. Clapham 1985: 1). This does not make for a term that is easily recognised on a map. As can be seen from the map (see Map 2.1) which illustrated the Brandt Report and which familiarised many people with a non-Mercator projection for the first time, the line which demarcated ‘the South’ (see also Burnell and Randall 2005) meandered across the northern hemisphere before plunging southwards to exclude Japan, Australia and New Zealand (see Table 1.1).

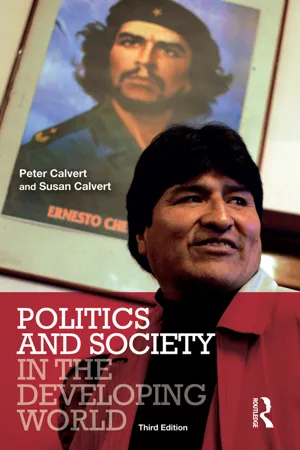

Plate 1 Where South meets North, Istanbul, Turkey

Hence some countries which observers would generally consider to have much in common become disconnected by the division of North and South. The geographical implications of the terms have proved rather too hard to overcome. Further, Mexico in North America, and Argentina and Brazil in South America, cannot simply be lumped together in a common ‘South’ grouping with countries in the Horn of Africa which are much newer, immensely poorer and altogether weaker states. And for people in English-speaking North America, the term South has long since been appropriated to designate the Southern states of the United States. There are also more specific questions that could be raised. China is not included because it was part of that Second World which was perceived to exist before the collapse of the USSR.

Table 1.1 GNP per capita of selected states, 1992

Source: World Bank (1994)

As suggested above, its size makes it virtually impossible to ignore, but its inclusion (or exclusion) may distort our view of other developing countries. (Similarly, generalisations about South Asia are distorted by the sheer human weight of India.)

NORTH AMERICA

MEXICO

Official name: The United Mexican States (Estados Unidos Mexicanos)

Type of government: Federal presidential republic

Capital: Mexico City

Area: 1,958,000 sq km

Population (2005): 106,202,903

GNI per capita (2005): $6,230 (PPP $9,600)

Evolution of government: Core of present state dominated by Aztecs before arrival of Spaniards 1519. Struggle for independence began 1810, effective 1821, federal presidential republic established 1824. In wars in 19th century lost half its national territory to the United States; the long dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz (1877–80, 1884–1911) introduced economic liberalism but demands for political reform triggered agrarian and labour unrest. The Mexican Revolution of 1910 was followed by far-reaching social reform and single-party dominance 1929–2000.

Main features of government: Constitution of 1917 established important social rights in programmatic form. Single-member single-ballot system modified to give proportional representation to opposition parties. Strong presidency increasingly restrained by bureaucratic immobility under long period of one-party dominance. Weak legal system. Thirty-two states with a common constitution each have elective governor and state legislature, contention for which paved way for breakdown of one-party rule.

SOUTH AMERICA

ARGENTINA

Official name: The Argentine Republic (Republica Argentina)

Type of government: Federal presidential republic

Capital: Buenos Aires

Area: 2,766,890 sq km

Population (2005 est.): 39,537,943

GNI per capita (2005): $3,720 (PPP $12,460)

Evolution of government: Spanish settlement began 1536 but present territory was never fully settled; autonomy proclaimed by Buenos Aires 1810 and independence for greater part of former Spanish viceroyalty 1816. Civil wars between Buenos Aires and interior temporarily arr...