![]()

Part I

Suicide

Statistics, research, theory and interventions

![]()

1 Suicide

Definitions, statistics and interventions at the international level

Stephen Palmer

This chapter provides a general overview to suicide definitions and global suicide statistics, and covers a number of issues, strategies and initiatives that are currently being undertaken to prevent suicide at an international level.

Definitions of suicide, parasuicide and deliberate self-harm

In attempting to assess whether or not suicide prevention strategies and interventions are working, it is important for researchers and statisticians to share a common definition of suicide and for the reporting of death by suicide in countries and by their national bodies such as prison and health services, to be identical or similar. However, this is not the case. De Leo et al. (2006) point out that the areas of terminology and definitions in suicidology are confusing. They state that ‘a satisfactory nomenclature of suicide should be applicable and usable both within and across all domains in which it is to be employed, whether the focus is research, clinical practice, public health, politics, or the law’ (De Leo et al., 2006, p. 5). O’Carroll (1989) highlights that it is not always clear that the death was self-inflicted or intended. Thus the process of death certification can bias mortality rate statistics (Brooke, 1974; Atkinson et al., 1975). However, studies have found that regardless of possible social influences upon the recording of suicide mortality rates, there is still a level of consistency across countries and regions (e.g. see Sainsbury and Jenkins, 1982). When it comes to the finer details, Linehan (1997) has raised the issue of definitional obfuscation and how it has made research more difficult when attempting to compare studies.

So what is suicide? It was in 1642 when a physician, Sir Thomas Browne, first coined the term ‘suicide’ in Religio Medici. The word ‘suicide’ is believed to derive from the Latin words sui – of oneself, and caedere – to kill; in other words, to kill oneself. However, this description is too simplistic for the purposes of research. In 1897 Durkheim defined suicide as, ‘All cases of death resulting directly or indirectly from a positive or negative act of the victim himself, which he knows will produce this result’ (1897/1951, p. 44). This is a sociological perspective.

In 1986 for research purposes across different sites, the WHO Working Group developed the following definition:

Suicide is an act with a fatal outcome which the deceased, knowing or expecting a fatal outcome, had initiated and carried out with the purpose of provoking the changes he desired.

(WHO/EURO, 1986)

This multicentre study was going to focus on non-fatal suicidal behaviour and initially used the term ‘parasuicide’ to describe this behaviour. The term ‘parasuicide’ was first introduced by Kreitman et al. in 1969 and subsequently was used in different ways by researchers and practitioners. Generally parasuicide and attempted suicide have been used interchangeably although often attempted suicide was seen as a subcategory of parasuicide and denotes a strong intention to die. The WHO/EURO Group decided that parasuicide could be described as follows:

An act with nonfatal outcome in which an individual deliberately initiates a non-habitual behaviour that, without intervention from others, will cause self-harm, or deliberately ingests a substance in excess of the prescribed or generally recognized therapeutic dosage, and which is aimed at realizing changes which the subject desired, via the actual or expected physical consequences.

(WHO/EURO, 1986)

In the 1990s, to overcome the definitional problems, the WHO/EURO Multicentre Study on Parasuicide decided the terms ‘parasuicide’ and ‘attempted suicide’ could be used interchangeably. However, this was still unsatisfactory and later the terms ‘fatal’ and ‘non-fatal’ suicidal behaviour were proposed (De Leo et al., 1999). It is worth noting that this contributed to the group being renamed the WHO/EURO Multicentre Study on Suicidal Behaviour.

This definitional debate has continued and in an attempt to overcome the particular problems inherent with the existing definitions, De Leo et al. (2006) have developed the following:

Suicide is an act with fatal outcome, which the deceased, knowing or expecting a potentially fatal outcome, has initiated and carried out with the purpose of bringing about wanted changes.

(De Leo et al., 2006, p. 12)

This definition would not include dangerous sports or other risk-taking activities as this behaviour is not intended to bring about ‘changes’.

De Leo et al. (2006, p. 14) have proposed a comprehensive category of ‘non-fatal suicidal behaviour, with or without injuries’. The definition becomes:

A nonhabitual act with nonfatal outcome that the individual, expecting to, or taking the risk to die or to inflict bodily harm, initiated and carried out with the purpose of bringing about wanted changes.

(De Leo et al., 2006, p. 14)

This should overcome the problems previously associated with the term parasuicide. However, in parallel with the above process, a number of organizations use different definitions or descriptions of suicide-related terms. This is illustrated by an American Psychiatric Association (APA, 2003) publication which has described a number of the key terms:

Suicide: Self-inflicted death with evidence (either explicit or implicit) that the person intended to die.

Suicidal ideation: Thoughts of serving as the agent of one’s own death. Suicidal ideation may vary in seriousness depending on the specificity of suicide plans and the degree of suicidal intent.

Suicide attempt: Self-injurious behaviour with a nonfatal outcome accompanied by evidence (either explicit or implicit) that the person intended to die.

Suicidal intent: Subjective expectation and desire for a self-destructive act to end in death.

Deliberate self-harm: Wilful self-inflicting of painful, destructive, or injurious acts without intent to die.

In the UK, Choose Life, the National Strategy and Action Plan to Prevent Suicide in Scotland, uses the following definitions:

Suicide: an act of deliberate self-harm which results in death

Deliberate self-harm: an act which is intended to cause self-harm, but which does not result in death. The person committing an act of deliberate self-harm may, or may not, have an intent to take their own life.

(Scottish Executive, 2002, p. 12)

Thus, when referring to the suicide research or statistics over a period of time it is important to clarify which suicide-related definition(s) are or were being used to ensure that the study outcomes can be compared without further adjustment. In the following chapters of this book, the WHO’s International Classification of Diseases ICD-10 codes (see Appendix 5) for self-harm and suicide are occasionally referred to although the data may also refer to ICD-9 codes if taken over a period of time.

International suicide statistics

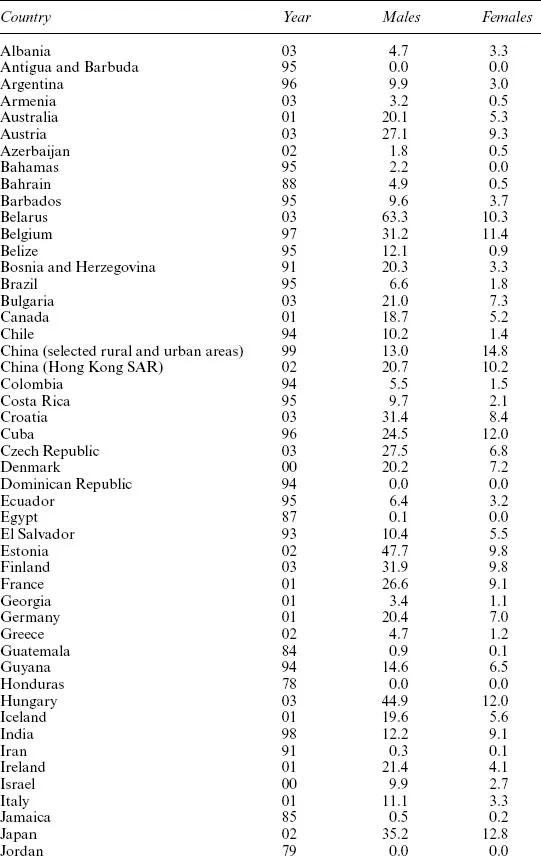

If we look beyond the health and caring professions, we could argue that governments and international bodies such as the World Health Organization have a responsibility to act on behalf of the public to reduce the incidence of suicide or non-fatal suicidal behaviour. Reducing the high level of reported suicides has become an incentive for the relevant authorities and bodies to take a proactive approach. But how much of a problem is suicide? In 1995 about 900,000 suicides were reported worldwide. According to the World Health Organization, future estimates based on current trends for the year 2020, approximately 1.53 million people will successfully commit suicide. Between ten and twenty times more people will attempt suicide. These figures are not precise but they do provide a frightening picture if nothing is done to prevent suicide. Table 1.1 provides the reported suicide rates per 100,000 of the population for countries across the world as of December 2005 published by the World Health Organization (WHO, 2005).

Some countries report a very high number of suicides for males per 100,000 of the population: Belarus: 63.3; Cuba: 24.5; Estonia: 47.7; Hungary: 44.9; Japan: 35.2; Kazakhstan: 50.2; Latvia: 45.0; Lithuania: 74.3; Russian Federation: 69.3; Slovenia: 45.0; Sri Lanka: 44.6. The Eastern Europe grouping have shared similar sociocultural and historical experiences which may partially explain the high suicide rate (see Bertolote and Fleischmann, 2002). A common factor with the majority of them is that they have experienced a period of political upheaval and change since the early 1990s. This has had an impact upon the population, jobs and support structures. Unemployment is a key factor with suicide in many countries. However, Cuba, Japan and Sri Lanka may have different causes and share the common factor of being island countries.

Although the rates of suicide per 100,000 of the population in some Eastern European countries are very high, due to the high population numbers in Asia, approaching 30 per cent of suicides occur in China and India.

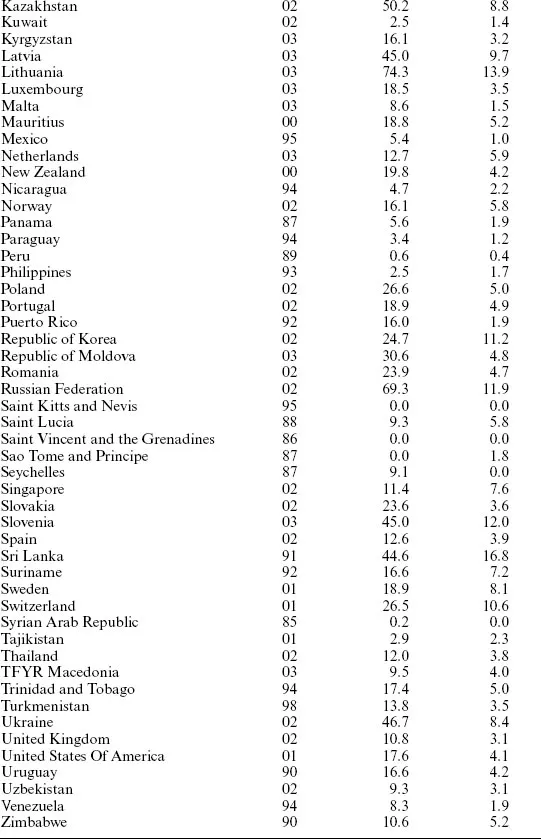

Figure 1.1 (adapted WHO, 2004a) highlights the evolution of the global suicide rates between 1950 and 2000.

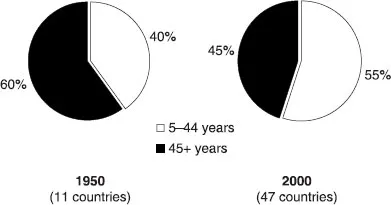

For males there has been a gradual but substantial increase of suicides since 1950 whereas there has been only a slight increase with female suicide in the same period. However, these figures do not provide a clear picture of what is exactly happening. In 1950 the data was based on eleven countries. Figure 1.2 (WHO, 2004b) highlights the shift in the distribution of suicides by age over the same period. In 1950 more people committed suicide in the 45 plus age group whereas in 2000 more people committed suicide in the 5–44 age range.

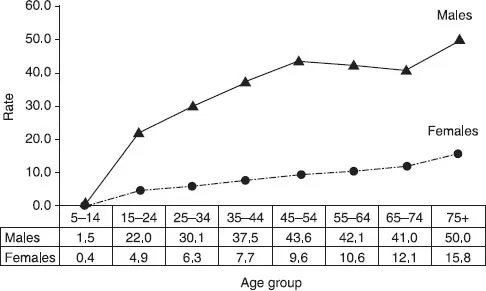

Additional countries were included in the 2000 assessment so the distribution shift should be treated with caution. The distribution of suicide rates, by age and gender in 2000 (see Figure 1.3), highlight the peaks for males in the 45–54 and 75 plus age ranges (WHO, 2004c). This is a cause for concern. Females also have an increase in suicide rates in the 75 plus range. One of the causes of suicide in this age group for both males and females is likely to be unbearable physical pain due to illness, although in many societies, loneliness, depression, alcohol abuse and complicated grief may also be factors (DeVries and Gallagher-Thompson, 2000). Often in older people depression goes unrecognized by family and health professionals as the focus is on the physical illness and not the associated psychological distress that such pain and/or an illness can trigger. Compared to younger people, older adults are more likely to achieve their goal of death by suicide and use more lethal methods. This suggests that they are less likely to be attention-seeking, and are more focused on completing suicide. The common methods used include firearms, hanging, gas and poison methods (Alexopoulos, 1996).

Table 1.1 Suicide rates (per 100,000) by country, year and gender, December 2005

Source: World Health Organization, 2005. Reproduced with permission.

Figure 1.1 | Evolution of global suicide rates (per 10,000), 1950–2000. |

Source: adapted from World Health Organization, 2004a. Reproduced with permission.

Figure 1.2 | Changes in the age distribution of cases of suicide between 1950 and 2000. |

Source: adapted from World Health Organization, 2004b. Reproduced with permission.

Figure 1.3 | Distribution of suicide rates (per 100,000) by gender and age, 2000. |

Source: adapted from World Health Organization, 2004c. Reproduced with permission.

However, taken at a global level, fewer older people commit suicide due to the age distribution factors, i.e. there are fewer older people, especially in the age band of 65 years and above. Thus 55 per cent of suicides are in the 5–44 years age band (see Figure 1.3).

Overall, Figure 1.3 highlights that there is a positive relationship between age and suicide rates for both males and females although there is a small reduction in suicide rates for males in the 55–74 age bands.

China

There is one anomaly in the statistics. In rural districts of China more women commit suicide than men. For Chinese mainland and selected rural districts in 1999, 6672 females and 5783 males respectively committed suicide (see WHO, 2003). There are a number of sociocultural-economic factors involved, as noted by Phillips et al...