What was the world like before television? Or radio broadcasting? An elderly few can remember the world before radio, and many can remember television’s advent. It wasn’t all that long ago. Today, however, most Americans spend more time with radio and television than they do at any other activity, including working and sleeping, and most Americans get most of their news from television. Obviously, we are dealing here with a phenomenon that is not only relatively recent but extremely important, one whose cultural impact is almost inestimable. Why, then, do we know so little about its development?

Unfortunately, most early broadcasters and inventors were too busy creating an industry, and surviving in what they had created, to think of recording its development for those who followed. Now most of them are no longer with us. At the same time, pragmatic reasons for knowing about broadcasting’s history are cropping up, and more people are becoming interested in it—and need to.

For example, regulation of space communications satellites follows principles established in international agreements in 1906, and even some from 1865. Early television programming of the 1940s and 1950s resembles the evolution of radio programming in the 1920s and 1930s. The beginnings of both cable television and pay-TV are discernible in a telephonic system in Budapest a century ago that distributed music and information for a fee. Videodisc recording is a descendant of Baird’s television experimentation in England during the 1920s. In 1945, Arthur C. Clarke wrote a description of space communications satellites. Programming on the Internet has borrowed extensively from broadcasting practices.

In addition to basic principles, current problems have their roots in the past. For instance, placing the international distress (“SOS”) frequency at 500 kHz in 1912—a location it didn’t leave until the late 1990s—led some years later to placing standard (AM) broadcasting on a portion of the spectrum utterly unsuited to competitive local broadcasting. New Jersey’s 1970s fight for a VHF television channel was really an attempt to overturn a 1945 political decision by the FCC that is a cornerstone of the United States television system. The still-mentioned Fairness Doctrine stems from specific statutory language in 1959, a 1949 FCC policy decision, a 1941 licensing case, the “public interest, convenience, and necessity” language in the Communications Act of 1934, and interstate commerce regulation right back to the Constitution in 1789. Indeed, there is hardly an argument on any aspect of modern broadcasting that does not leave one with a feeling of having heard all this before!

1.1 The Concept of Mass Communication

“Mass communication” is the effort to share information or entertainment with lots of different people through a technological intermediary. We can trace this concept all the way from primitive spoken language and cave drawing, and we can follow the development of modern mass communication from the introduction of print 500 years ago to the increasingly elaborate technologies of the motion picture, radio, and television.

When one imparts ideas and information “to whom it may concern” through some mechanical or electromechanical means, usually rapidly, over considerable distance, to a large and essentially undifferentiated audience, and when there are many copies of the message (duplicates of a newspaper or individual television sets tuned in)—then we have mass communication.

A mass medium is (a) the means—a printing press or broadcast transmitter— by which the communicator produces and distributes copies of the message to the mass audience or (b) the industry that operates that means. A mass audience, usually large but sometimes not, consists of people who typically are related only by their attention to the same message. The distance between the source and the audience can usually be measured in miles, but a newspaper restricted to a campus is still a mass medium. The audience may be highly specialized rather than undifferentiated—an abstruse scientific journal may reach only a few specialists in that field. Circulation can be small. Although Letters to the Editor and call-in programs on radio involve some person-to-person communication, they still reach a large audience. Unit cost to the consumer, typically low, may be high, as it was with early-day television. Messages usually are transmitted and received at or about the same time—but many books are timeless in appeal. And there are gray areas, such as truckers using CB radio and a chat room on the Internet.

1.2 Early Communication

Mass communication began when cave dwellers first shouted a warning to all the tribe within earshot or, closer to modern methods, used technology such as a horn, bells, a hollow-tree drum, a signal fire, a flag of cloth or wood, or a piece of reflecting metal to maintain surveillance of their surroundings and improve their chances of survival. Eventually, people used more complex ways to transmit their culture to the next generation. The prehistoric but realistic paintings of animals and animal hunts on cave walls probably served as hunting lessons for younger members of the tribe and possibly also as religious symbols intended to ensure good fortune on future hunts. In this way the tribe could refresh their memories and build on the lessons already learned without each generation having to start all over again. These two types of communication, transient and recorded, are to be found today.

Slowly, over thousands of years, pictures of people, places, animals, and things became conventionalized and stylized into symbols. Although most people still learned through oral tradition or storytelling, small ruling classes and religious elites developed a system of pictographs and hieroglyphics—the printed, stamped, inscribed, painted, or carved “word.” But written language was a code that only a tiny fraction of society could understand, with oral tradition serving the rest.

Communication typically depended on human senses and abilities. When speed was uppermost—a prearranged code of signal fires carried news of the fall of Troy across most of Greece in a single night—the amount of information transmitted had to be small. Sending a long or complicated message took longer—as with the Romans’ semaphore and flashing light devices—and sometimes involved a human carrier using any available means of travel, whether it was a horseman using a Roman road or an Incan royal messenger using a high-speed foot trail in the Andes.

After the fall of Rome in the fourth century A.D., the Roman Catholic Church preserved much of the knowledge of the past in its monasteries. By painstakingly reproducing books by hand, the monks managed to preserve some of the culture of the past that was not being transmitted by word of mouth among the illiterate masses.

The first real change in mass communication came with the introduction of the printing press and movable type—separate wood block or tin letters that could be temporarily combined into desired words that would form a page from which to print many copies. The first use of movable type in the Western world is ascribed to Johannes Gutenberg of Mainz, Germany, who either developed his own press, type, and ink, or applied Far Eastern techniques in 1456. The new process soon spread across Europe and its colonies, although its use was sometimes held up by the Church, which objected strongly both to losing its monopoly of recorded communications and to the increase of secular publishing that the Renaissance had stimulated.

Although greatly faster than hand copying, printing was restricted to the relatively slow speeds of hand-operated presses until the 1800s, when steam-driven presses became practical and common. Low-cost printing made books available to many more people, was a stimulus to literacy, standardized the appearance of alphabets, and enhanced the idea of the utility of books, reducing their artistic and increasing their social importance.

1.3 The Rise of Mass Society

Significant changes were taking place in Western society in Gutenberg’s day. A new middle class of traders and merchants, between the upper nobility and the peasant poor, kept themselves informed of foreign developments in technology, commerce, and politics. Reformation within the Catholic church and revolt from without brought new patterns of societal control to Europe. The spread of secular news and knowledge brought a loosening of religious control over everyday life. In addition, the long-lasting feudal system began to give way to parliamentary government as the population, spear-headed by the growing merchant middle class, began to question the spending practices of monarchs.

At the same time, a renaissance of learning and art was taking place. Starting in southern Europe, the fine arts flourished, science and technology advanced, knowledge was acquired from the East, and new ideas once again became acceptable. Versatile men appeared, like Leonardo da Vinci, who could work in medicine, science, military technology, art, and music. Sometimes noble families, who still held most of the money, and consequently power, acted as patrons of a high culture of artists, musicians, architects, and some scientists—all of whom produced their work for this small elite or for the Church.

In many civilizations, the common people who provided the economic base for high culture had their own thematically and technically simple folk culture from which the high culture often borrowed. Folk culture of the Middle Ages took the form of fairs, circuses, traveling minstrels, song and story sessions, and morality plays, providing some religious instruction and a great deal of diverting entertainment.

In the 1700s the Industrial Revolution spread from England to the continent. Machines, driven by water and steam instead of human and animal power, supplied an increasing amount of manufactured goods that the home couldn’t produce, at prices that individual craftsmen couldn’t match. By the 1800s, manpower needs of industry, expansion of international commerce, and the start of mechanized agriculture led people toward city living.

The growing cities furnished an industrial base, great amounts of information and people who wanted it, and a market for mass-produced entertainment and information. The density of population made distribution easy. The local tavern or coffee shop continued to serve as a center of communications as it had for hundreds of years, but information now came in posted broadside advertisements or printed newspapers in addition to the traditional word of mouth from travelers. This situation was analogous to the “first color TV set in town” being in the local bar.

Although literacy was increasing, thanks to public and private schooling in the 19th century, improvements in transportation and technology were more important to communication in the increasingly urbanized society. Steam power permitted the mechanization of printing presses, made transportation by water faster and more reliable, and allowed the railroad (supplemented by improved carriage and wagon roads) to knit all parts of a country together. Greater occupational specialization, particularly in cities, led to an increased use of money instead of barter and to an increased need for news and entertainment—mass communication.

Most important, in the 19th century the first electrical communication devices (the telegraph and then the telephone) decisively overcame the problem of speed without dependence on unaided senses or transportation. By the mid-1800s, both the socioeconomic systems of the more developed countries and their emerging technologies were ready for introduction of the components of the mass electronic media we know today: radio and television broadcasting.

1.4 Early Electrical Communication

For centuries the technological development of communication involved distance, speed, number of copies, and quantity of content. Each new technology was a balance of these demands. The Pony Express could deliver mail faster than any other method, but only a few pounds at a time. If many copies of a communication were required, or if each copy contained many pages, production might take much more time and space than for a more limited output.

While printing answered the fundamental question of quantity, it did so at the expense of speed—the time needed for gathering information, setting it in type, and printing, binding, and distributing newspapers, magazines, or books. Improving routes and methods of transportation shortened distances, but the speed with which news could travel still was limited by how fast man, animal, train, or ship could go.

Combining distance with speed became possible with the development of telegraph systems, such as the mechanical semaphore originated by the Romans and forgotten during the Middle Ages. Rediscovered, the semaphore systems of several European countries reached a high degree of efficiency in the late 1700s. They were fast and simple for short messages, but the equipment was expensive to build and operate, and many towers would be needed to relay signals over long distances. Their inefficiency for long messages and their high personnel costs limited use to the most urgent needs. Although lights could be used at night, the semaphore was essentially a daytime, good-weather system that, like all telegraphs, achieved point-to-point rather than broadcast communication.

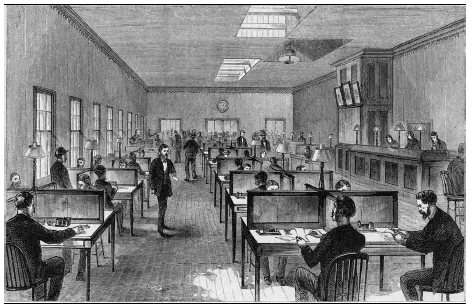

1.4.1 The Electrical Telegraph

The semaphore was quickly rendered obsolete by the electrical telegraph. Electricity could travel through a wire at almost the speed of light, and it needn’t worry about fog or bad weather. Wherever a wire could be strung, there the electrical telegraph could go; nor did operators have to be within sight of each other. All that was needed was a source of electricity, a switch or key to manipulate the current, a wire to conduct electricity, and a mechanism—the element inventors changed most frequently—to “read” the transmitted message visually or audibly.

In the United States, the first practical telegraph was invented by Samuel Finley Breese Morse, then well-known as an artist. In 1832 he learned from a fellow passenger on a ship returning from Europe about the electromagnet and work being done on electrical signaling for railways in England. Morse’s first electrical telegraphy instrument, in 1835, used pulses of current to deflect an electromagnet, which moved a marker to produce a written code on a strip of paper. A year later he modified the...