![]() I Virtual Reality as Communication Medium

I Virtual Reality as Communication Medium![]()

1 The Vision of Virtual Reality

Frank Biocca

Taeyong Kim

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Mark R. Levy

University of Maryland

When anything new comes along, everyone, like a child discovering the world, thinks that they’ve invented it, but you scratch a little and you find a caveman scratching on a wall is creating virtual reality in a sense. What is new here is that more sophisticated instruments give you the power to do it more easily. Virtual reality is dreams.

– Morton Heilig1

The year is 1941. Engineers and industrialists are introducing a new medium to the country. Few can predict the significant influence of this new “gadget” with the odd name, television–vision at a distance. It is not just a novelty in a research lab or an amusement at a World’s Fair. Although a technological reality, it is not yet a psychological and cultural reality. In the early 1940’s there are less than 5,000 sets in the United States. But soon, the light from the TV screen will flicker in every home and mind in the country.

Change the channel. The year is 1988.2 Engineers and industrialists are introducing another new medium to the country. Like television, virtual reality (VR) is not just a novelty in a research lab or an amusement at a World’s Fair. More than 50 years after the introduction of television, VR technology presents us with devices such as the head-mounted display, a television set that wraps itself around our heads both literally and metaphorically.

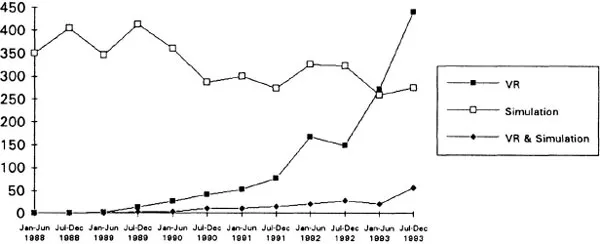

Fig. 1.1. Graph shows the frequency that the terms virtual reality and simulation were used in 96 daily newspapers from Jan. 1988 to Dec. 1993 (see footnote 3).

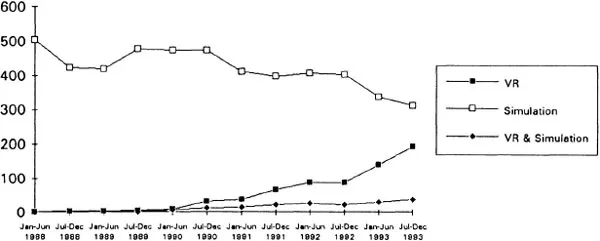

Fig. 1.2. Graph shows the frequency that the terms virtual reality and simulation were used in 176 news and business magazines from Jan. 1988 to Dec. 1993 (see footnote 1).

This book is an attempt to explore the vision of communication in the age of virtual reality. VR dangles in front of our eyes a vision of the media’s future, changes in the ways we communicate, and the way we think about communication. The medium that tantalizes us so has gone by a number of names: computer simulation, artificial reality, virtual environments, augmented reality, cyberspace, and so on. More terms are likely to be invented as the technology’s future unfolds. But the enigmatic term virtual reality has dominated the discourse. It has defined the technology’s future by giving it a goal – the creation of virtual reality. Virtual reality is not a technology; it is a destination. In this book we look toward this destination and collectively ask ourselves a deceptively simple, but profoundly nuanced question: What is communication in the age of virtual reality?

Virtual reality? It is a quirky phrase, but it seems inspired. Attributed to the quodlibetic mind of Jaron Lanier, the phrase united the many voices of it rivals–virtual environments, virtual worlds, virtual space, artificial reality–into a single chant seeming to emanate from a distant future. Not everyone likes it. The scientific community at places like MIT, University of North Carolina, and at military research centers were uncomfortable from the start with this upstart, pop culture term. On the net and in scientific journals like Presence, researchers insisted that their work would be better described by terms like virtual environments or simulation.

But Lanier’s VR cyberslogan and its uncertain vision was spread at warp speed by a technophilic press. For TV, magazine, and newspaper journalists virtual reality was a “sexy” term for computer experiences. Many of the smitten reporters were children of the 1960s (e.g., Rheingold, 1991). To these and other observers the more pedantic term, simulation, suggested something more akin to silicon implants than a slogan for info-revolution. In article after article the vision of VR was dangled in front of a public entranced by the curious pleasures of interactive technology. In a field that was dominated by military applications, the childlike, dreadlocked Lanier sounded more like a poet or new age prophet than a “computer geek.” In a typical early interview in 1989, the pied piper of VR played his song:

Virtual reality will use your body’s movements to control whatever body you choose to have in Virtual Reality, which might be human or be something different. You might very well be a mountain range or a galaxy or a pebble on the floor. Or a piano … I’ve considered being a piano. … You could become a comet in the sky one moment and then gradually unfold into a spider that’s bigger than the planet that looks down at all your friends from high above. (Kelly, 1989, p. 34).

This was a very different vision of the computer, something more in tune with science fiction or fantasy play. Some researchers in areas like scientific visualization and flight simulation were uncomfortable with what this vision promised. “We can’t really do that,” some objected. “Hype!” others protested. But word of the vision of virtual reality ricocheted around the interiors of the public imagination and resonated with some primal desire for a dream machine. Lanier and his supporters in the press provided an outlet for that ancient desire.

The meteoric trajectory of the phrase virtual reality is a metaphor for the rise of virtual reality technology as a whole. The first phase of the diffusion of a technology is the knowledge phase (see Valente & Biardini, this volume). Figures 1.1 and 1.23 plot the different trajectories of the phrase virtual reality and a competing term for the same technology, simulation, in newspapers and magazines in the early 1990s. As the graphs reveal, usage of the term simulation declined and phrases like virtual environment barely registered a blip on the public radar screen. Usage of the phrase virtual reality rose rapidly, especially in newspapers where it surpassed usage of the more general term simulation.

Along with the term cyberspace, the phrase virtual reality has come to symbolize both our enthusiasm and ambivalence about social and cultural transformation through technology. For some, virtual reality is the first step in a grand adventure into the landscape of the imagination. Virtual reality promises a kind of transcendence of the limits of physical reality. Others are more cynical or uncomfortable about the whole idea of virtual reality. They feel the phrase is an oxymoron; it promises the impossible. Like an Escher drawing of impossible staircases, it offers a vivid vision of something that can never be. But reality has never been the concern for some virtual reality enthusiasts; they want a computer-generated world where an Escher staircase can be experienced rather than imagined. As respected VR computer scientist Fred Brooks put it, the technology allows one to experience “worlds that never were and can never be” (Brooks, 1988). If the reader finds that Brooks’ words seem vaguely familiar, perhaps you hear the echo of a very ancient promise of all media technologies.

The 2,000-Year Search for the Ultimate Display

Is virtual reality technology the first step toward the ultimate display or the ultimate communication medium? Some of the pioneers of virtual reality have heralded it as the “ultimate form of the interaction between humans and machines” (Krueger, 1991, p. vii) and “the first medium that does not narrow the human spirit” (Jaron Lanier, quoted in Rheingold, 1991, p. 156). Although some of this rhetoric is clearly overblown, VR embodies a number of conceptual breaks with existing media as it tries to reach out to some vision of the ultimate medium.

A powerful and unusual vision of the ultimate medium surely gripped the work of one of the most revered pioneers in computer graphics and VR, Ivan Sutherland (1965): “A display connected to a digital computer gives us a chance to gain familiarity with concepts not realizable in the physical world. It is a looking glass into a mathematical wonderland. … There is no reason why the objects displayed by a computer have to follow the ordinary rules of physical reality. … The ultimate display would, of course, be a room within which the computer can control the existence of matter” (pp. 506, 508).

At first, the idea of the “ultimate display” seems rather startling. Many see Sutherland’s paper as particularly inspired and novel; it is often quoted. Sutherland was clearly a visionary, but his dream is an ancient one. The dream of the “ultimate display” accompanies the creation of almost every iconic communication medium ever invented. There are two aspects to this dream, and VR shares these with older iconic media like painting, photography, film, and television. The drive powering the creation of many of these media has included (a) the search for the essential copy (Bryson, 1983), and (b) the ancient desire for physical transcendence, escape from the confines of the physical world. Seeking the essential copy is to search for a means to fool the senses –a display that provides a perfect illusory deception. Seeking physical transcendence is nothing less than the desire to free the mind from the “prison” of the body.

Almost 2,000 years before Sutherland’s musings about the ultimate display, we can see the stirrings of the search for the essential copy in a story recounted by the Roman naturalist, Pliny. It is an anecdote from ancient Greece, but imagine it, if you will, as a modem competition between two VR programmers to see who can produce the best perceptual illusion:

The contemporaries and rival of Zeuxis were Timanthes, Androcydes, Eupompus, and Parrhasius. This last, it is recorded, entered into a competition with Zeuxis. Zeuxis produced a picture of grapes so dexterously represented that birds began to fly down to eat from the painted vine. Whereupon Parrhasius designed so lifelike a picture of a curtain that Zeuxis, proud of the verdict of the birds, requested that the curtain should now be drawn back and the picture displayed. When he realized his mistake, with a modesty that did him honour, he yielded up the palm, saying what whereas he had managed to deceive only birds, Parrhasius had deceived an artist. (Pliny, 1938, pp. 64–65)

In later years, painters expressed the desire for the essential copy as a desire for a canvas that would become a magic window or mirror on the virtual world created with brush strokes. This vision of the ultimate “windowed” display finds expression in the world of the painter, architect, and theorist of linear perspective Leone Battista Alberti (1462/1966). He espoused the technology of perspective to produce a painting so perfect that it would dissolve into a window–an ultimate display of the virtual scene.

The search for the ultimate display sometimes involved a celebration of the ability to use the senses for communication. Today, communication through sensory-intensive means like “visualization” is sometimes opposed to communication through more abstract means such as words or numbers (Mitchell, 1986). In the past, this desire for displays that “spoke” to the senses sometimes expressed itself as a critique of other forms of representation like words, narratives, and texts. For example, the painter Francastel was so moved by the power of the perspective realism of Masscio’s Renaissance masterpiece, Tribute Money, that he declared; “Henceforth man will be defined not by the rules of narrative, but by an immediate physical apprehension. The goal of representation will be appearance, and no longer meaning” (Francastel, quoted in Bryson, 1983, p. 3). In this prediction of the future, it is interesting that the sensory realism of the essential copy is seen as opposed to the text and narrative–the icon would eventually overcome the linguistic sign.4

By 1760, prior to the arrival of photography, de la Roche was predicting the emergence of a medium that would lead users to question reality:

You know the rays of light that reflect off bodies are like an image that paints these bodies on polished surfaces, the retina of the eye, and for example, on water, and on mirrors. The elemental spirits have sought to fix these passing images. They have composed a material … so that a painting is created in the blink of an eye … and … trace on canvases images that are imposing to the eye and make one doubt one’s reason, so much so that what we call reality may be nothing more than phantoms that press upon our vision, hearing, touch, and all our senses at once. (Authors’ translation of quote in Fournier, 1859, pp. 18, 20; see Biocca, 1987)

With the arrival of photography, the dream of the essential copy became even more intense. Far more stunning and prescient than Sutherland’s vision is that of Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. In 1857 Oliver Wendell Holmes, father of the famous jurist, saw a glimpse of the future of VR when he lifted a stereoscope to his eyes for the first time. After the initial strain, as the lenses forced his eyes to fuse the different images only inches away, Holmes saw a vision. Holmes prophesied the creation of a giant universal database that would house essential copies of all things, something on the scale of Ted Nelson’s hypermedia Xanadu. Holmes, of course, saw the essential copy through the eyes of the 19th century. Globe-trotting adventurer-scientists would stock a curio cabinet of essential samples of reality, a collection so large that it would be housed in an immense stereographic library or museum. Essential copies of all things would be gathered from around the world and kept for 3-D examination in the vast, cyberspatial museum of forms (see Biocca, 1987). After peering through his stereoscope, Holmes took up his pen and wrote the following in the prophetic voice that seems to accompany much writing at the birth of a new medium: