This is a test

- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A Preface to T S Eliot

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

T. S. Eliot is arguably the most influential poet of the 20th century, and The Waste Land one of its most significant poems. This introduction to the life and works of T.S. Eliot sets his writing clearly in the context of his times. Outlining his life and cultural background and their effect on his work, Ronald Tamplin examines his poetry and focuses in detail on three major works: The Waste Land, Four Quartets and the play, Murder in the Cathedral.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access A Preface to T S Eliot by Ron Tamplin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

The Writer and His Setting

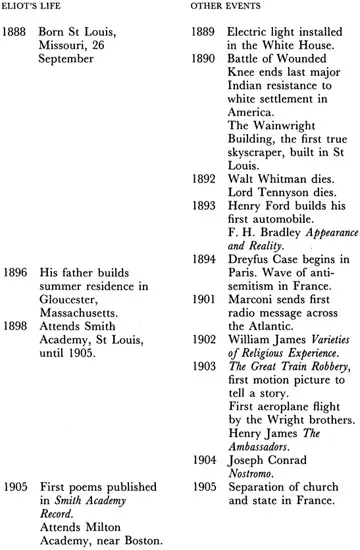

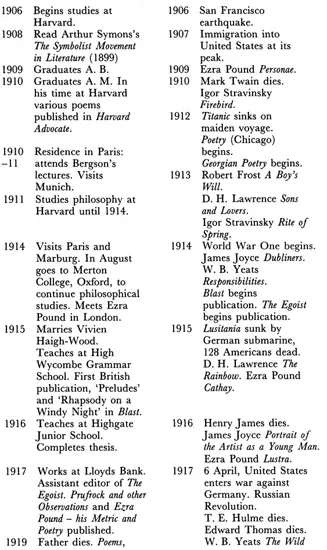

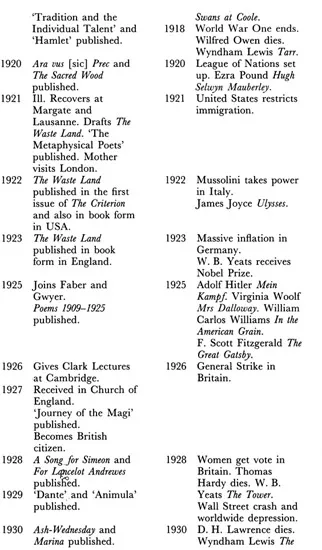

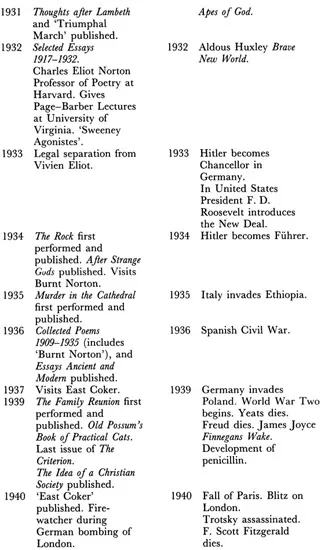

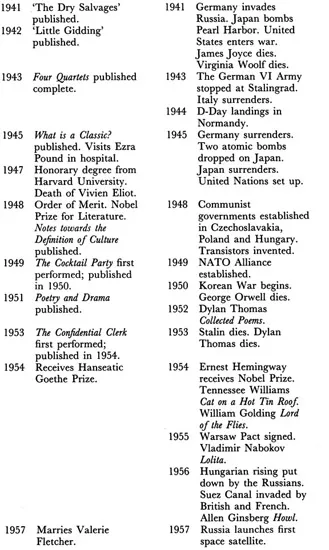

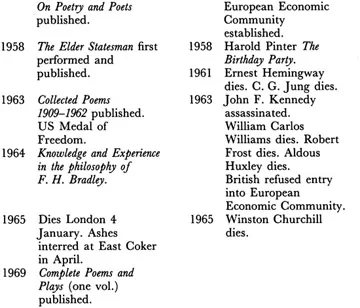

Chronological table

1

Briefly, the essentials

About T. S. Eliot the essentials are clear. He was one of the finest poets writing in English in the first half of the twentieth century. More than any other he determined the course that poetry has taken since but has himself remained fresher and more substantial than most poets. He is still emphatically modern. His decisive contributions are the metric he established in his first book Prufrock and Other Observations (1917), the form he pioneered in The Waste Land (1922) and the content he attempted in Four Quartets (1943).

His literary criticism is more constantly interesting, challenging and responsible than most on offer in this often tired and overworked area. His social criticism raises uncomfortable issues none too congenially, nearly all of which are still relevant to the terms of contemporary society.

As a dramatist he is more important for unlikely triumphs, from Murder in the Cathedral (1935) to the immensely successful Cats derived posthumously from the stolid whimsy of Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats (1939), than for his real stature in the theatre. Nevertheless anyone who thinks of writing verse drama now is well advised to study all Eliot’s plays and his candid and impressive essay Poetry and Drama (1951).

It is no exaggeration to say that, through his metric, he gave poetry a new language. His rhythms deliberately disengaged from English iambic patterns and asserted the poet’s individual voice. In England Browning had already done this and Whitman in America, but both too quirkily for general use. Eliot’s more accommodating and all-purpose rhythms helped to fracture the mould more widely, so that now in metrics anything goes provided only that it satisfies the more or less exacting ear of the poets as they listen to the words they write. It was a liberation without doctrine and so has formed no school, but in a more than temporal sense anything written now is post-Eliot. His heavily rhythmic writing as in ‘Sweeney Agonistes’ or Murder in the Cathedral or ‘The Hollow Men’ has been less used, being more limiting.

A second release that Eliot effected was in the range of materials permitted to poets. Most societies seem to think that certain subjects are appropriate to poetry and others not. Eliot helped foster a sense that was increasing in the poets of the first two decades of the twentieth century, that poetry must engage all aspects of society and supposedly ‘sordid’ materials. ‘Preludes’ would stand as an example. This sense has been entirely absorbed. The other major area that Eliot brought back as a possible currency was the rigorous examination of religious questions, and in this his influence has been less pervasive. In fact, as society absorbs one type of material it seems to let others slip. There is a frequent and current sense that major religious writing is not central and is, therefore, ‘non-poetic’. Eliot’s reputation, both in his time and ours, has suffered from that. Reputations and quality apart, it would probably be more difficult to get a publisher to accept a poem like Ash-Wednesday now than it was in the 1930s. Diffused religion begot by Wordsworth on Zen can get by, though, and the general sharpening of tone and terms that Eliot effected has, perhaps rather crudely, been neglected.

Finally, Eliot still seems close to us now in that he asks some good questions. His critical ideas which are part and parcel of his life as poet are challenging, and because they range so widely, investigating the whole structure of culture, he remains totally of our time. The question of a useful poetic language may be something that each poet writing now answers as an individual, not bowing to a norm, but the nature of the culture in which we live, the education we receive and administer, the values we live by, our stance towards material possessions, towards other societies, classes and racial groups, the relation of the individual to the state or the institution, all these questions continue unbroken, often intensified, from Eliot’s time to our own. And these are the questions – overwhelming ones – that stir in all the poems and govern the direction of his critical writings. It is certainly to be seen as part of his stature that he has been a major critic. No poet writing now has built up so impressive a body of criticism to be taken as an adjunct to his centre, the poems. Eliot’s mind is not always one we can easily like. He has a tendency to propose ideals which are remote from practicalities and not in themselves attractive. He is often magisterial in a way that does not appeal to a less tractable age. Sometimes he seems out of touch with us. I particularly like a remark in 1920: ‘If Pindar bores us, we admit it; we are not certain that Sappho was very much greater than Catullus; we hold various opinions about Virgil; and we think more highly of Petronius than our grandfathers did.’ But of course this is out of touch for us. We should not expect it to be other than coloured by its own class and social circumstances, and these are not ours. The point is that we do expect him to answer our own standards and demands, precisely because he speaks habitually to questions which concern us. He is still, then, genuinely modern. The whole range of his mind thrusts into our present.

At the same time Eliot induces in many, even among his advocates, tangles of perplexity not easy to unravel. There is guilt and suffering in the man, which, if not quite relished, seems at times entertained and lacking in proportion. He was a curious combination of warmth and stiffness, of concern and coldness. At times he seems too emphatic in his certainties, at others hagridden by unwarranted nightmare. His poems and plays volunteer his private life to the public, but he wished desperately to remain private and concealed. There has been a lot of speculation about Eliot’s psychology, his sexuality and his suffering. I have chosen not to enter too much into this. I have no wish to discount the relevance of a writer’s personality and circumstances to the writings, but it is easy to get the balance wrong and forget that the reason we are interested in Eliot at all is because the poems he wrote are good poems. Eliot’s own distaste for biography was not just a wish for privacy but a critical position. It is true that it is a position that Eliot does not always himself adopt, but I have tried, as far as I can, to use Eliot as a clue to the poetry rather than the poetry as a clue to Eliot.

Beyond this, though, in the particular matter of Eliot, seen as ‘the man who suffers’, I share the perplexity that so many people who knew Eliot and so many who write about him indicate when they try to evaluate the nature of that suffering. Peter Ackroyd’s biography gives documentation of much illness of all sorts but never fails to show how he worked through it – as if he found creativity somewhere in ill health. Bertrand Russell, not the best of witnesses, it’s true, thought that Eliot and his first wife enjoyed their troubles. This is too glib to be right, but Eliot did undoubtedly have a capacity for self-examination that is, at times, self-invention. In so far as part of what he examined and analysed was his own suffering, so he adds to it and extends its effects. The suffering becomes willed as much as inflicted. None the less, willed or not, it had to be borne. It is real enough, but what is that reality? Above all it seems to me there is no simple and romantic equation between ‘the man who suffers’ and the mind that creates.

T. S. Eliot will sometimes frustrate our expectations and remain enigmatic to us if we try to force his life and work into patterns of our own making, but there will always remain the one inescapable imperative, Ezra Pound’s injunction: ‘Read him.’

To aid in that there follows first a brief biographical outline which presents Eliot’s life as a journey from St Louis, Missouri, to East Coker, Somerset, and then that journey is traced three times – through Eliot’s religious development; through a sequence of poets who impinge upon him; and through his critical writings. I then analyse (or read) a number of Eliot’s important poems to exhibit the range of his abilities.

St Louis

Eliot was born on 26 September 1888, at 2635 Locust Street, St Louis, Missouri. St Louis was then establishing a role for itself, set between the East and the West and the North and the South of the North American land-mass. Earlier the city had been the regular place to launch out on the drive to the West, though at this time it was losing its position to Chicago. Eliot himself spoke of the importance of St Louis in his life: ‘the utmost outskirts of which touched on Forest Park, terminus of the Olive Street streetcars and to me, as a child, the beginning of the Wild West.’ His family, though, had come out of the East. His grandfather, William Greenleaf Eliot, had been born in New Bedford, Massachusetts, and after graduating at the Harvard Divinity School in 1834 set out for the frontier city of St Louis, which was rich from the fur trade but as yet primitive and unhealthy. Dr Eliot was a Unitarian minister, and for the Unitarians, St Louis was very much missionary territory, without a minister and without a church. Within two years his church was built. It was not the only institution that this awesomely dynamic man established. He helped to make the St Louis schools the best in the Union and to set up a university. Friends hoped that it would be called the Eliot Seminary, but he resisted the name and in 1857 Washington University of St Louis began its life. Dr Eliot was later Chancellor of this university. He worked against slavery, and used his influence in the Civil War to engage St Louis on the side of the Union. He also organised hospital and relief service in the war, ran his parish and taught metaphysics in the university. In his seventy-seventh year he died, a year before his grandson Thomas Stearns Eliot was born. Eliot wrote that, none the less, ‘I was brought up to be very much aware of him:

so much so that as a child, I thought of him as still the head of the family…. The standard of conduct was that which my grandfather had set; our moral judgments, our decisions between duty and self-indulgence, were taken as if, like Moses, he had brought down the tables of the Law, any deviation from which would be sinful. Not the least of these laws, which included injunctions still more than prohibitions, was the law of Public Service; it is no doubt owing to the impress of this law upon my infant mind that, like other members of my family, I have felt, ever since I passed beyond my early

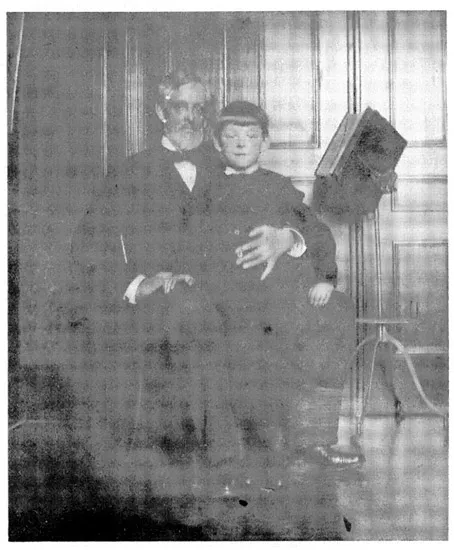

Young Tom Eliot with his father, 1898.

irresponsible years, an uncomfortable, and very inconvenient obligation to serve upon committees.

Eliot was the youngest of the seven children born to Charlotte, wife of Henry Ware Eliot. Henry Ware Eliot did not go into the Unitarian ministry but rather carried his father’s high ethical standards into business as chairman of the Hydraulic Brick Company of St Louis. There were considerable opportunities for the development of business interests in St Louis. Rivers were vital to transport in America during the nineteenth century, and St Louis was built to advantage close to the confluence of the Missouri and the Mississippi rivers.

The Mississippi itself had its impact on the young Eliot. In ‘The Dry Salvages’ he writes:

I do not know much about gods; but I think that the river

Is a strong brown god – sullen, untamed and intractable,

Patient to some degree, at first recognised as a frontier;

Useful, untrustworthy, as a conveyor of commerce;

Then only a problem confronting the builder of bridges.

The problem once solved, the brown god is almost forgotten

By the dwellers in cities – ever, however, implacable,

Keeping his seasons and rages, destroyer, reminder

Of what men choose to forget. Unhonoured, unpropitiated

By worshippers of the machine, but waiting; watching and waiting.

Is a strong brown god – sullen, untamed and intractable,

Patient to some degree, at first recognised as a frontier;

Useful, untrustworthy, as a conveyor of commerce;

Then only a problem confronting the builder of bridges.

The problem once solved, the brown god is almost forgotten

By the dwellers in cities – ever, however, implacable,

Keeping his seasons and rages, destroyer, reminder

Of what men choose to forget. Unhonoured, unpropitiated

By worshippers of the machine, but waiting; watching and waiting.

‘The river’, he says, ‘is within us’, and it carries through time ‘its cargo of dead negroes, cows and chicken coops.’ In a poet whose poetry is not noticeably conditioned by his early visual surroundings, such words become even more impressive. Eliot, in fact, is intertwining in his account the qualities that impressed him in the condition of St Louis in the 1890s.

The description of the river here is no abstract catalogue of attitudes that might conceivably be taken to rivers, but an accurate, if slightly cool account of the Mississippi, turbid and treacherous, with massive variations in its flow and, until it was finally bridged by James B. Eads in 1874, a formidable barrier between the East and the West. The St Louis Bridge was a crossing vital to the development of the transcontinental railroads and helped make St Louis the most important city on the Mississippi. Undoubtedly too it was seen as a victory by ‘worshippers of the machine’ of whom nineteenth-century America had its share.

In later years T. S. Eliot was to say, ‘I am very well satisfied with having been born in St Louis.’ In making that assessment he was probably influenced by a sen...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

- Dedication

- FOREWORD

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- PART ONE: THE WRITER AND HIS SETTING

- PART TWO: CRITICAL SURVEY

- PART THREE: REFERENCE SECTION

- INDICES