This is a test

- 416 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This text has established itself as the best general introduction to Russian history, providing a forceful and highly readable survey from earliest times to the post-Soviet State. At the heart of the book is the changing relationship between the State and Russian society at large. The second edition has been substantially rewritten and updated and new material and fresh insights from recently accessible research have been incorporated into every chapter.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Russia by Edward Acton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Chapter 1...........................................................................

The origins of the Russian Empire

The pleasing simplicity with which it is possible to summarize Russian history has led historians of various persuasions to seek one key factor to explain all. Among the most plausible of these is the physical setting of the East European Plain in which Russian society evolved. Three points merit particular attention: the low yield of the land, the absence of natural barriers, and the network of major rivers.

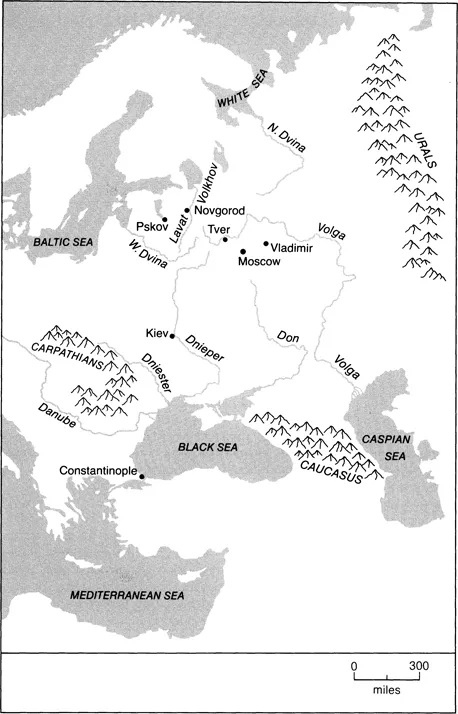

At the end of the Soviet period, only just over one-tenth of the territory under Moscow’s rule was actively cultivated, while two-thirds were unfit for farming of any kind, and over half was virtually uninhabitable. Even on the best land, agriculture is handicapped by adverse climatic conditions. The richest soil, that of the so-called ‘black earth’ region which stretches from the south-west into Siberia, suffers from recurrent drought during the growing season and yields are frequently further devastated by thunderstorms and hailstorms in the harvest season. Moreover, until the seventeenth century these fertile regions were dominated by livestock-rearing nomadic tribes. The low yield of the land available to the Russians made it difficult for their settled agricultural communities to generate the necessary resources to resist nomadic raids. What further delayed settled development was the lack of natural protection against such raids. Only the Urals interrupt the East European Plain, and this low range of scattered hills is little more than a notional boundary between Europe and Asia, presenting no substantial obstacle to migration and military advance. Once a settled community able to defend itself was established, on the other hand, little stood in the way of a rapid extension of its power over more primitive peoples. The unification of a vast region was further facilitated by the waterways which all but link the Baltic, White, Black, and Caspian Seas. It was the rivers which to a large extent dictated the lines of settlement, the main trade routes, and the location of power centres. And it was precisely in the central region of European Russia, from where the great rivers radiate outwards, that the state of Muscovy arose in the fifteenth century.

Map 1 Kiev and Muscovy: rivers, seas and mountains

The huge country which these natural conditions fostered, however, was at a relative disadvantage when compared to the West. The harshness of the Russian climate, from the ice of the winter freeze to the slush of the spring thaw, severely hampered transport between her far-flung regions, and until the eighteenth century she had no secure access to western seas. Russia’s neighbours, on the other hand, not only enjoyed a generally higher grain-yield but also benefited from the rapid expansion of European, and especially overseas, commerce from the fifteenth century onwards. Economic advantage tended to place these states at a military advantage as well. That Russia should become involved in sustained conflict with them over land and resources was by no means geographically determined. But once she did so, the demands made upon her backward economy were necessarily heavy and the social repercussions profound. Unchanging physical conditions cannot, on their own, explain the development of social life, but Russia’s history can only be understood in the context of her geopolitical environment.

It was in the ninth century that an independent Russian state emerged. The tribes who came to be known as Russians were East Slavs, one of the three branches of the Slavic-speaking peoples. They had been settled on the great steppe to the north of the Black Sea for centuries, probably since before the birth of Christ. But until now they had been dominated by a succession of tribes from east and north – Cimmerians, Scythians, Sarmatians, Goths, Huns, Avars, and Khazars. The relatively stable conditions established by the last of these peoples in the eighth century fostered the development of viable urban trading centres dominated by a native aristocracy on which a state could be built. An important role in this process was played by merchant mercenaries from Scandinavia. Wave upon wave of Viking expeditions made their way down the waterways, attracted by the lucrative trade with Constantinople in the south, and willing to serve native chieftains. The precise relationship between these ‘Varangians’, as the Russian chronicles call them, and the Slav tribes has been the subject of fierce controversy since the mid-eighteenth century. Russian national pride has taken offence at the notion that the first Russian state, centred on the city of Kiev, and the very name ‘Rus’ should have been of Scandinavian origin. Generations of Russian and Soviet historians, moreover, have been at pains to demonstrate the organic evolution of East Slav society towards statehood. The chronicles, however, on which historians depend for much of their knowledge of the period, speak of the warring Slavs inviting the Varangians ‘to come and rule over us’. This has given rise to the view that the state of Kiev was the creation of the adventurers from the north. The Varangians appear, in fact, to have acted as a catalyst, accelerating commercial and political development. They provided Kiev with the ruling house of Rurik, but his descendants and their retinue were rapidly assimilated by the native Slavs and made little cultural impact.

At its prime in the eleventh century the Grand Principality of Kiev asserted at least nominal control over a vast area extending from the Vistula in the west to the Don in the east, and from the city of Kiev itself in the south all the way to the Baltic. The great bulk of the population was engaged in agriculture, but the early princes derived their wealth from booty, tribute, and commerce. Basing themselves upon existing towns, they encouraged and participated in both local and international trade, exporting furs, honey, wax, and slaves. The city of Kiev and the great northern centre of Novgorod rivalled the leading cities of Europe in size, wealth, and architectural splendour. The Rurik dynasty intermarried with royalty from as far away as France and England and with families as august as that of the Byzantine Emperor. The Slav state became a considerable force in eastern Europe.

It was during the Kiev era that Russia was converted to Christianity. By the late tenth century her most important neighbours had each adopted one of the great monotheistic religions, and contacts with their adherents were growing. The inferiority of Kiev’s paganism, in terms of spiritual vitality and sophistication, was becoming apparent. For the Prince, provided he could carry his retinue with him, the option of conversion provided a major diplomatic asset. Kiev’s vital commercial ties with Constantinople encouraged and were powerfully reinforced by the choice of Byzantine Orthodoxy rather than Catholicism, Islam, or indeed Judaism, to which the Khazars had been converted. In 988 Vladimir I was baptized, married the Byzantine Emperor’s sister, and proceeded to convert his people. The fact that there already existed written translations of the Scriptures and liturgy in Church Slavonic – intelligible to East and South Slavs alike – greatly assisted the process. The new religion spread out from the cities to the countryside and though pagan resistance and ritual lingered for centuries, especially in the north, evangelization was on the whole remarkably peaceful and swift.

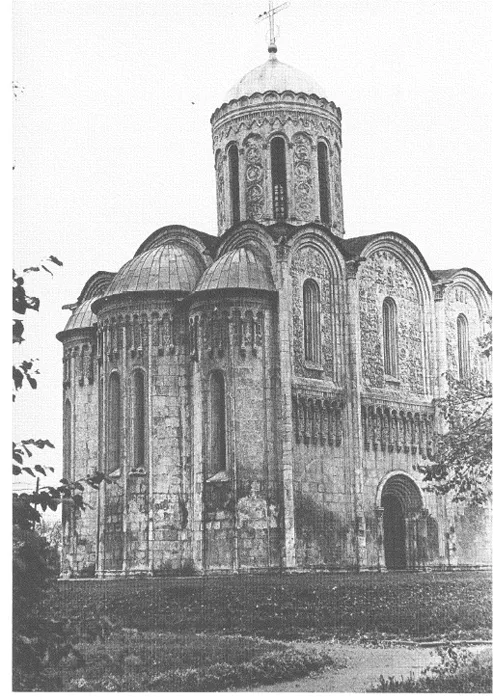

For Russian culture, the conversion was decisive. All levels of society, from prince to slave, gradually learned to articulate their values and aspirations through the medium of Byzantine Christianity. Byzantium provided the model for art, architecture, and literature. It served, too, to reinforce patriarchal features of Russian society and the Russian family. Women’s subordination in public and economic life was complemented by their inferior status in the eyes of the Orthodox Church. Canon law unreservedly upheld male authority to the point of sanctioning (limited) wife-beating. The Church, it is true, played an important role in developing legal codes which, compared to other patriarchal societies, provided a relatively dignified and humane system for upholding women’s honour. From early in the Orthodox era, for example, rape within marriage was grounds for divorce, and from the fifteenth century a woman could divorce her husband for adultery. On the other hand, there was no equivalent of Western medieval literature of courtly love. Nor did either the Renaissance or the Reformation penetrate Russia, and it was not until the seventeenth century that Western influence made any significant impression on the Orthodox mould.

1.1 The twelfth-century Cathedral of St Dmitrii in Vladimir, a major centre of early Orthodox church-building. The massive scale and elaborate design reflect the wealth and influence of the Church.

The ethos of the Orthodox faith strikes the non-Orthodox as markedly conservative and passive. Where Western theology was stimulated by classical philosophy and remained open to development, Russia inherited a body of doctrine settled for all time by the great Ecumenical Councils. Where the Latin Church sought to bolster faith with reason, to explain and rationalize dogma, the East was content with mystery. It was not by reason, sermons, or even direct reference to the Bible that Orthodoxy was sustained and expressed, but rather by the celebration of the liturgy. The emphasis on communal worship was reflected in the extravagant architecture of churches and cathedrals, and their lavish interior decoration, lined with mosaics, frescos, and icons and lit by candles burning in elaborate candelabra. The ‘Kievan Primary Chronicle’ has left an immortal account of the impression such a setting made upon Vladimir’s envoys to Constantinople: ‘They led us to the edifice where they worship their God, and we knew not whether we were in heaven or on earth. For on earth there is no such splendour or such beauty, and we are at a loss how to describe it.’1 The drama of the service itself, led by ornately robed clergy and accompanied by the rich fragrance of incense, the chiming of church bells, and the moving sacred chant, was central to the faith. Here God was present. The aesthetic rather than intellectual tenor of Orthodoxy provided little encouragement to innovation and individualism. Despite an impressive tradition of saintly hermits and mystics, the hierarchy tended to emphasize ritualistic conformism. ‘Man’s own opinion,’ said Joseph of Volokolamsk, an immensely influential abbot of the late fifteenth-early sixteenth century, ‘is the mother of all passions. Man’s own opinion is the second fall.’2

The sociopolitical impact of this ethos, however, should not be exaggerated. The philosophy inherited from Constantinople was sufficiently flexible and complex to permit different social groups in Russia to emphasize different facets, to imbibe and accentuate the ideas which spoke to their own predicament. As elsewhere, the secular power took full advantage of the respect for authority which the Church preached. But, equally, decade after decade, century after century, outbursts of peasant protest were justified with direct reference to Orthodox doctrine. For all its cultural importance, the Byzantine heritage is among the least plausible ‘keys’ with which to explain the distinctive features of Russian history.

It was as an institution that the Church did play a very substantial role in shaping the Russian state. A network of monasteries, bishoprics and parishes spread rapidly across Kievan Rus and the Church became a major landowner. With the clergy having a near monopoly upon literacy until the seventeenth century, the Church was able to develop an unrivalled administrative structure. It penetrated the countryside in a way that the rudimentary power of the princes could not hope to do. Moreover, this elaborate institution was under the unified jurisdiction of the Metropolitan of Kiev ‘and all Rus’, established soon after Vladimir’s conversion. As such it constituted a formidable political force which the Metropolitan, supported and appointed (until the fall of Constantinople in 1453) by the Greek Patriarch, used to good effect. When Kiev broke up and the Russians came under the sway of stronger powers to east and west, the Church worked vigorously to maintain its own unity. In the process it nourished the ethnic consciousness of the East Slavs and greatly assisted their eventual political reunification.

Kiev’s prime was short-lived. The commercial wealth of the south was undermined from the latter half of the eleventh century as constant incursions by the nomads of the south-east impeded trade with Constantinople. During the twelfth century the Crusades hastened a permanent shift in the trading pattern of the region, the overland route between East and West being supplanted by the Mediterranean route. Political decisions accelerated Kiev’s decline. In 1054 the most impressive of Kiev’s rulers, Yaroslav the Wise, divided his patrimony among his five sons. His heirs did not practise primogeniture so that by 1100 there were a dozen principalities and the number grew during the next century. Despite the enormous prestige enjoyed by Grand Prince Vladimir Monomakh early in the twelth century, and the enduring sense of Russian unity bequeathed by Kiev, the old capital’s effective authority evaporated. In the north-west, where commerce continued to flourish, the leading cities were able to impose tight restrictions on the power of their local princes. In Novgorod the princely office became effectively elective and sovereignty came to reside in the vigorous veche, or city council, dominated by leading landowners and merchants. Elsewhere the growing number of princes and their retinue (boyars) turned to land-ownership and direct exploitation of the peasantry to supplement their dwindling profits from trade. Under these conditions the country became subject to constant civil war between rival princes, and increasingly vulnerable to incursions from Swedes and Germans to the north, Lithuanians, Poles, and Hungarians to the west, and above all Turkic tribes to the south. A major movement of population from the unstable south to the more secure centre and north-east further weakened the old capital, and by the second half of the twelfth century the new Grand Principality ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Maps

- List of Illustrations

- List of Tables

- Acknowledgements

- Prologue

- 1. The origins of the Russian Empire

- 2. The genesis of Russian ‘absolutism’

- 3. The prime of the Empire

- 4. The Great Reforms and the development of the revolutionary intelligentsia (1855–1881)

- 5. Industrialization and Revolution (1881–1905)

- 6. The end of the Russian Empire (1906–1916)

- 7. 1917

- 8. Civil War and the consolidation of Bolshevik power (1918–1928)

- 9. Stalin’s revolution from above (1928–1941)

- 10. World War and Cold War (1941–1953)

- 11. Stabilization under Khrushchev and Brezhnev (1953-mid-1970s)

- 12. Stagnation and decline (mid-1970s-1985)

- 13. Perestroika and the fall of the Soviet Union (1985–1991)

- 14. Epilogue

- Bibliography

- Index