![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Nation

One issue above all was made so problematical by eighteenth-century events that it continues to perplex the Scots even today: their nationhood – the need continually to ask ‘Who are we?’ The answer, of course, has never been entirely straightforward. A convoluted political and religious relationship with the English, the unavoidable fact of extreme geographical proximity and deeply rooted ethnic and linguistic ties have ever muddied the water. Yet the late-medieval conflicts with England, continuing sporadically into the sixteenth century, had somehow fashioned a collective identity among Scotland’s disparate inhabitants, infusing them with a profound sense of their own separateness. If knowing what properly defined a Scot remained complicated – first amid intensifying hostilities between the country’s Gaelic-speaking Highlanders and Scots-speaking Lowlanders and then because of the people’s own violent religious differences following the Reformation – a working solution to the problem, frequently repeated and almost universally endorsed by all ranks and persuasions, gradually emerged. Whatever else they might be, the Scots, by the later seventeenth century, could at least be sure that they were not English.

The impact of the Treaty of Union, by whose ratification in 1707 the last Edinburgh Parliament agreed that Scotland should be incorporated into a newly forged British state governed from the English capital, was therefore necessarily unsettling. Deciding whether to establish these new arrangements in the first place, as well as which of several possible variant forms they might take, inevitably caused internal convulsions. All manner of other issues were also left unresolved for the Scots by the creation of a new polity. Key questions were in fact settled not in the surprisingly laconic treaty but in the slow and difficult evolution of political practice over succeeding decades: What precisely was to be the new role of Scotland’s politicians and institutions? How might the Scots secure their own interests within a predominantly English state? And would Westminster seek to preserve or to erode Scotland’s distinctiveness? Even less clear were the ramifications for the Scots’ identity. In particular, if nationhood were ordinarily expressed through the free exercise of sovereign self-government, had Scotland itself also ceased to exist in 1707? Whatever their views, and however they preferred to answer these questions, all Scots were forced to confront the consequences of Union. It is with the background to this epochal event that we must begin.

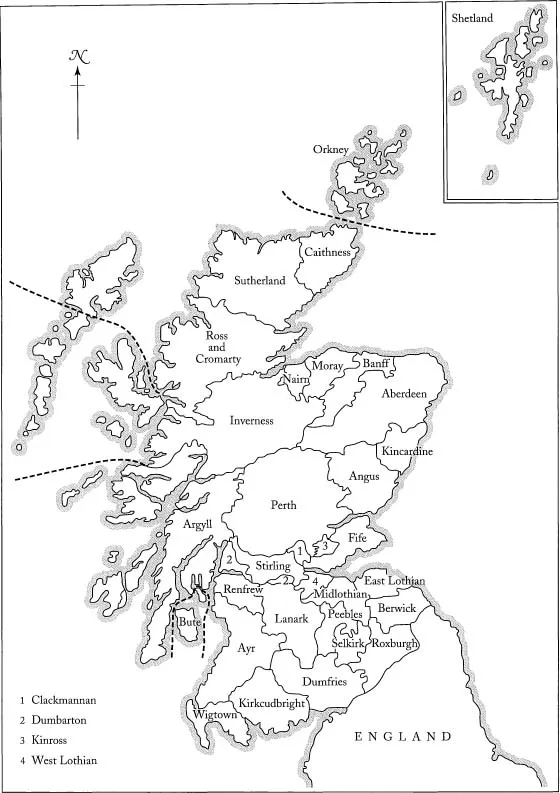

Map 1 Eighteenth-century Scotland

Convergence and crisis

In 1700 the separate kingdoms of Scotland and England still had a considerable distance to travel before their slightly awkward marriage could be consummated. Mutual suspicion, at times verging on a complete breakdown in relations, marked the notably cantankerous years leading up to the treaty. Superficially it can appear that Union was the result of irresistible processes of convergence – that, if not quite inevitable, it was the product of long-term forces pressing the two neighbours ever closer to some kind of lasting political unification. While this interpretation certainly dominated between the eighteenth and mid-twentieth centuries, recent historiography, less deferential towards older pieties, has begged to differ. It is now generally agreed that, although specific trends of convergence can indeed be identified as far back as the sixteenth century (especially those arising out of both people’s shared formal commitment to Protestantism), so too were deeply rooted patterns of divergence also strongly evident. These were in fact still driving the two old enemies further apart until a surprisingly advanced stage in the pre-Union proceedings.

The political developments of the seventeenth century were not the least of the hindrances to closer and happier Anglo-Scottish relations. The experience of the ‘regal union’ or ‘union of the crowns’, stemming from 1603 when James VI of Scotland had succeeded his mother’s childless cousin Elizabeth, Queen of England, thus beginning an often unhappy arrangement by which two historically antagonistic kingdoms shared the same monarch, lay at the root of the strained relationship. Pro-unionists ever since 1603 have pointedly interpreted this royal connection as a milestone on the road to greater intimacy; and the Treaty of Union was indeed, as we shall see, in many ways a solution to the constitutional and diplomatic tensions which were James VI and I’s peculiar legacy to his successors (though it was not, it should be added, the only possible solution: elsewhere in seventeenth-century Europe, the Habsburgs’ awkward tenure of both the Bohemian monarchy and the German emperorship did not result in a unified state). But the intrinsic problems of multiple monarchy, especially when it is remembered that a third throne – that of Ireland – came along with James’s English inheritance, led many Scots to even greater resentment of England’s pre-eminence within the British Isles. It also prepared them to resist any suggestion that their own future might lie with absorption in what would inevitably be an anglocentric polity.

Historians have lately grown fond of interpreting seventeenth-century British history in terms of this so-called ‘three kingdoms’ perspective. Yet the tangled relationships between the separate polities ruled over by the Stuarts after 1603 do seem to provide the key to understanding many of the age’s major events. The political and military crisis of the late 1630s and 1640s, for example, which lost James’s son Charles I not only his three crowns but his head, might convincingly be explained as a disastrous manifestation of the problems latent in Britain’s haphazardly arranged multiple monarchy, the patchwork product not of coherent planning or rational strategy but of the biological accident of James’s inheritance. In this context Charles’s catastrophic attempt to import essentially English religious forms into a very different Scottish environment, so compelling his irate Scottish subjects to apply pressure to their shared king by successfully invading northern England in the so-called ‘Bishops’ Wars’, was the immediate trigger which ignited the combustible materials which had accumulated in the south by 1642.

Attempts by successive Stuarts to consolidate the narrowly personal union of 1603, and to make the multiple monarchy more congruent and more manageable, also met with little success. James himself had tried in vain to persuade his English and Scots subjects to form a unitary state. His grandson Charles II likewise failed to convince the sceptical statesmen of London and Edinburgh that royal proposals for economic union (1668) and parliamentary union (1670) were in their mutual interests. Indeed, it says something not only about the obvious administrative attractions but also about the formidable obstacles in the way of Anglo-Scottish union that between 1652 and 1660 it was Cromwell’s all-conquering revolutionary regime, the only real military dictatorship in British history, which briefly boasted this unique achievement among its dubious accolades.

The fundamental contradiction of multiple monarchy – a compelling pragmatic case for institutional integration so as to make possible its more effective management, yet also continuous resistance from each kingdom arising out of distinctive identities and traditions – runs throughout the entire seventeenth century, afflicting all who shared, or aspired to share, a wider British vision. The difficulties of tripartite government, however, were not only those of Stuart ministers or Cromwellian administrators struggling from London to rule three incorrigibly divergent peoples. Seen from the perspective of the Scottish people or the Edinburgh Parliament, multiple monarchy was not that much more satisfactory. Even discounting the illadvised attempts by both Charles I and Charles II to impose an Anglican model on the Scots’ distinctive religious institutions, always regarded as the locus classicus of the threat posed to Scotland by a monarch whose own ideas and inclinations were disproportionately shaped by English experiences, the decades prior to the Treaty of Union offered abundant further evidence against the regal union. In particular, this period had underlined the fact that the convoluted inheritance of James VI and I would tend more often than not to work to the disadvantage of the smaller, weaker and more distant of the two main Stuart kingdoms.

Not only had a reigning King of Scotland deigned to visit his subjects just twice since ascending the English throne (James VI in 1617 and Charles I in 1633). To the obvious problem of absentee monarchy was also added the grave constitutional risk that decisions affecting Scotland’s crown – and indeed other vital aspects of her national life – would effectively be dictated by the English Parliament. On this point the seventeenth-century evidence was distinctly discouraging. It was mainly agreements between Westminster and Charles II that had brought about that king’s unexpected return to his late father’s three British thrones in 1660. Again in 1688–89 it was a narrow conspiracy among English parliamentarians which engineered William and Mary’s successful invasion and James VII and II’s consequent loss of his predecessors’ British patrimony. In both cases Edinburgh was left to grapple with the results of unforeseen English decisions which nevertheless had the most drastic implications for Scotland’s own government. Finding itself negotiating the conditions on which these monarchs might govern in Scotland long after their general suitability had already been determined by London, the Scots Parliament was more than once forced to accept that, precisely because they were not the concern of an exclusively English parliament at Westminster, Scotland’s vital interests were being compromised by a fundamental asymmetry in the geo-political architecture of seventeenth-century Britain. Thus when William after 1689 had once more raised the possibility of parliamentary union, it is not surprising that many Scots, including some who would later oppose the 1707 treaty, favoured it. Indeed, the proposal eventually foundered more on English apathy than on Scottish resistance.

This assessment of Scotland’s chronic weakness in its relations with its own sovereign, which had attained widespread credibility throughout the political community at the turn of the eighteenth century, had most recently been borne out by the events of the 1690s. England’s preponderance in national wealth, military and naval power and political ambition was becoming ever more obvious. Under William’s firm hand the Westminster Parliament was emerging at the helm of a fiscal-military state of considerable authority, leading a Continental coalition at war with the France of Louis XIV between 1689 and 1697 and engaged in confident imperial and commercial extension as far afield as the Indian subcontinent and North America’s eastern seaboard: small wonder that the views and advice of the king’s Edinburgh parliamentarians, especially if unwelcome or contrary, were ignored. To compound insult with injury, William’s wars also badly hit Scotland’s export trade. Although they closed many northern European ports to all British vessels, the Scots’ exclusion from England’s Atlantic trade and consequent over-dependence upon North Sea commerce in particular meant that they suffered disproportionately. Worst of all, with armies still substantially controlled by kings rather than parliaments, Scottish soldiers and officers, as part of the royal army, were routinely used by William, alongside those of his regiments raised south of the Border, to pursue the crown’s strategic objectives on the Continent.

By far the most dramatic recent case of English priorities overriding Scottish interests, however, was the infamous Darien scheme in which the Scots Parliament had lent its full support to an attempt to establish a trading colony on the coast of Central America. Inspired by a desire to emulate English and Dutch colonial successes, the first expedition set sail in July 1698 with orders ‘to proceed to the Bay of Darien … and there make a settlement on the mainland as well as the said island, if proper (as we believe) and unpossessed by an European nation or state in amity with his Majesty’. Although a second voyage was made in 1699, the venture was an unmitigated disaster. The territory in question was claimed by Spain. William, whose peaceable relations with Madrid were an integral part of his strategy against Louis XIV, declined to employ his diplomatic or military resources to protect his ill-advised Scottish subjects from Iberian wrath: the king’s refusal to intervene may have greatly pleased rival English trading interests (particularly the powerful East India Company) but it caused predictable fury in Scotland. It remains true that tropical disease and inept planning were also factors in a financial catastrophe which lost investors huge sums. Yet the wider constitutional lessons were no less evident to politically literate Scots. Labouring under a form of multiple monarchy which granted the peripheral kingdom little leverage over its own sovereign and no say at all in the parliamentary deliberations of the dominant nation, Scotland was in crying need of some kind of re-working of the British systems of government.

Just as these painful examples of Scotland’s progressive marginalisation were accumulating, contemporary events also offered further evidence that the country’s existing political apparatus was becoming less and less effective. Indeed, even eventual opponents of the 1707 treaty seem to have become convinced that the status quo – a kingless kingdom within a multiple monarchy whose centre of gravity lay elsewhere – was no longer a viable option. The ensuing debate about Scotland’s destiny, however, was strongly coloured by the economic crisis which afflicted the country throughout the 1690s. Partly this was the product of the Continental wars disrupting Scottish trade; but it was also the result of a succession of dreadful harvests across Scotland through the second half of that blighted decade. Starvation, famine and unemployment occurred on an alarming scale, all the more worrying against the backdrop of the deepening disaster in Darien, and ever greater awareness of England’s contrasting plenty and prosperity, which clouded the last years of the old century.

Most Scottish politicians by 1700 were therefore agreed that fundamental change was needed to guarantee national survival. For some, like Andrew Fletcher of Saltoun, with his fiery temperament and lairdly prejudices but also his brilliantly original mind, the solution lay in a linked series of measures which he recommended as commissioner (i.e. parliamentary representative) for East Lothian and as the author of several topical pamphlets, most notably Two Discourses Concerning the Affairs of Scotland (1698). These included draconian measures to bind the poor to the soil and deport vagrants to the Venetian galleys; the establishment of a militia subject to ferocious discipline; a prohibition on the charging of interest; a programme of concerted agricultural development; some equalisation of personal wealth; and, most intriguingly, a speculative scheme reorganising Britain and Europe into roughly equal states under the public-spirited control of their propertied elites. Fletcher’s latter-day admirers understandably gloss over the illiberal elements in this extraordinary package. But the consistent preference for devices which would check the growth of central authority also betrays his sense that Scottish liberties and Scottish interests were coming increasingly under threat from an Anglo-Dutch commercial and military superpower. This perception, leading him strongly to oppose the Treaty of Union in due course (even though he had earlier supported William’s union proposals), has naturally made Fletcher an icon for modern anti-unionists. Yet the far-fetched nature of his constitutional proposals, at least to his unconvinced contemporary opponents, also spoke volumes about the state of the country. In essence, they confirmed that Scotland, unquestionably a nation in crisis, was rapidly running out of credible alternatives.

Treating for Union

This was the variegated longer-term background to the making of the treaty: a confusion of centrifugal and centripetal forces pulling England and Scotland apart while simultaneously pushing them together, all of them at work in an environment in which informed Scottish opinion was becoming more and more convinced that the nation’s condition required drastic improvement. The first years of the new century were not much different, except that, just as the reasons for seeking an Anglo-Scottish union became even more cogent, so resistance to it also grew more intense. England’s burgeoning wealth and power were unarguable facts which still bewitched most Scottish observers. Yet it was actually a new problem which was to prove decisive. Crucially, it was this that finally convinced English politicians, long at least as sceptical as their Scottish counterparts, that union with the king’s much smaller and poorer northern kingdom was in their own interests. Typically, however, this issue also generated even greater tension in Anglo-Scottish relations in the short term, at first making any kind of voluntary union between the kingdoms appear only a remote possibility.

The new factor was the royal succession, an issue rendered peculiarly fraught by William’s childlessness and the growing awareness that Mary’s younger sister Anne, whose only surviving child died in that year, was likewise unable to supply a living heir. Given the very real possibility (actually borne out in 1715) that the exiled James VII and II or his son might exploit these failings by attempting a Catholic restoration by force of arms, aided by their protector and co-religionist Louis XIV, who strongly backed their claim, Westminster once again decided to take matters into its own hands. In 1701 the Act of Settlement was passed in London, specifically excluding Catholics from the English throne. It settled the destination of the crown after Anne’s death on a distant but impeccably Protestant candidate: Sophia, Electoress of Hanover and the German grand-daughter of James VI and I.

This was in one sense an understandable precaution given contemporary paranoia about the twin evils of Popery and tyranny supposedly associated with the deposed Catholic line of the Stuarts. Yet the Act was greeted with horror in Edinburgh. As a unilateral English decision, it flagrantly ignored legitimate Scottish interest in the identity of future British monarchs: just as in 1660 and 1688, Westminster, concerned solely with English interests, had pre-empted any decisions by the Scots Parliament and effectively presented Scotland with a fait accompli. This realisation produced two important reactions. First, an extensive and thought-provoking debate developed among the parliamentarians as they sought to arrive at an appropriate Scottish response: encouraged by Fletcher, they considered both the succession and, more widely, the need to secure greater control over their monarch. These discussions culminated in Scotland’s own Act of Security, which explicitly restated the country’s prerogatives with regard to the Scottish crown and contained thinly veiled threats that they might yet prefer a non-Hanoverian candidate unless specific restraints (particularly strengthening the powers of the Edinburgh Parliament) were placed on the government. An accompanying piece of legislation, the Act Anent Peace and War, pointedly asserted Scotland’s right to pursue an independent foreign policy after Anne’s death. By the time she reluctantly gave the royal assent in 1704 in return for the Scots’ grant of supply (i.e. taxes), the former statute had been watered down, but the limitations proposed on royal power, strongly influenced by Fletcher’s florid denunciations of executive excess, remained prominent.

The second and no less inevitable consequence of Westminster’s undiplomatic Act of Settlement was a pronounced chilling in Anglo-Scottish relations. Coming on top of centuries of intermittent mistrust and with Darien and the economic consequences of renewed English wars against France adding fuel to the fire, it is not surprising that the Scots responded aggressively. For the English, however, Scotland’s Act of Security was itself both an affront and a threat, seemingly blackmailing their own future monarch so as to obtain concessions for Scottish interests and, what was worse, leaving open the possibility of a rival, perhaps even a Catholic, candidate securing the throne of Scotland as a likely precursor to an attempt also to claim the English crown. London duly responded to what it perceived as an ultimatum with one of its own.

The Alien Act of 1705 gave the Scots just ten months to repeal the Act of Security and either formally endorse the Hanoverian succession or enter into meaningful negotiations about a political union between the kingdoms. If Scotland refused, then the rights of English citizenship enjoyed by Scots since James VI’s time would be revoked and their duty-free imports of cattle, coal, sheep, wool and linen into England terminated. This was a crude but effective ploy, striking directly at the Scots’ most vulnerable points: in the words of Sir John Clerk of Penicuik, who, significantly, gravitated from early scepticism to eventual support for union, it was simply an unavoidable truth that ‘our country’s fortunes depend on England; the only wealth we have comes from the horses and cattle we sell there’. Following this English move, jeopardising key economic activities about which the Scots were acutely sensitive, one of the most notorious incidents in Anglo-Scottish relations occurred: anti-English rioting in Edinburgh was accompanied by the execution of the unfortunate Captain Thomas Green and two crewmen of the English merchantman Worcester – one of them ironically a Scot himself – on Leith sands in 1705, on a trumped-up charge of piracy.

As will be clear, the forces impelling the Scots and English to consider union in the first five years of the century were once again simultaneously stirring up the most determined opposition. Yet this time, after much soulsearching and not a little arm-twisting, the critical new departure which was England’s willingness to embrace Scotland, together with deepening fears among the Scots about the diminishing range of sensible alternatives, eventually settled the issue. Thus it was that in the summer of 1705 the Scots Parliament finally nomin...