The Salience of Language

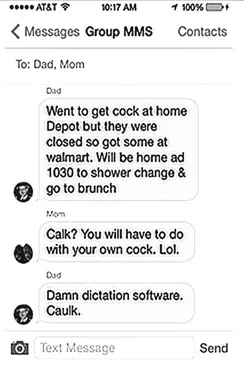

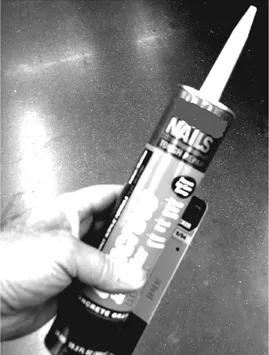

Language is a primary tool of the trade in psychotherapy, a tool with which we communicate and from which we infer meaning. Language misunderstandings can also prove to be barriers in treatment. My husband and I still laugh about a text he sent by voice dictation (see Figure 1.1). He did not review it before it was sent, and there was a significant error. When I got his message, I laughed and playfully responded to the literal message, knowing quite well that he meant something else. He clarified his communication, and later sent a picture with a message, “Here I am, caulk in my hand” that left no confusion.

All humor aside, what comes to mind from this are the many ways in which our clients communicate, sometimes saying things they do not mean, sometimes sharing things they don’t yet understand and often sending mixed or confused messages that require clarification. We know better than to accept all client communication at face value, and we remain open and prepared for the rest of the story.

We discover the meaning that our clients attribute to their experiences as we listen sensitively, for the goal of listening is to understand who this client is as a unique individual, not just someone with a DSM-V diagnosis. Therapists sometimes communicate in ways that clients do not understand, and clients may take non-intended meaning from our communication. Our clients want to understand us and to be understood, and we must be cognizant of the fact that they will nod and smile even at things that confuse and baffle them. What is “clear” to the therapist does not always reach the client’s mind, and we forget that therapy communication is not a photocopy machine where an exact likeness emerges. Like the old “gossip” game, our sometimes lengthy, abstract or vague messages get lost in translation even during the short time lapse between our mouths and the client’s brain.

So how do we best understand what our clients are saying and communicate in ways so that we are accurately heard? First, we match and mirror the client’s language, and clarify the client’s intent, while being culturally informed and sensitive. Client Centered Therapy intentionally incorporates clarification in the universal, “What I hear you saying is…” When we offer clients an opportunity to “correct” us and clarify their intent, we settle into the comfortable back-and-forth rhythm of transparent communication, and we come to understand the meaning behind their words. The language of therapy is about meaning-making, and by matching and mirroring our clients, we demonstrate attunement and empathy, and they feel heard and understood.

Meaning-Making: Integrating Verbal and Non-Verbal Communication

Non-verbal communication, in conjunction with language, offers material from which we hypothesize and infer meaning. Clients of all ages use metaphor in language, stories, art and play, regardless of age; clients also have preferred communication styles or modalities, such as writing or drawing, stories, puppets, games, soldiers, knights or sand tray. When we know and understand our clients and their preferred modes of communication, the therapeutic connection is stronger, as the client feels felt and understood (Siegel, 2010, 2012).

Peterson and Fontana (2007) compare a client’s verbal and non-verbal communication to a foreign language. When we learn that language, there is less loss in the translation. Speaking the same language enriches communication, deepens trust and enhances the building of relationships. When we neglect to speak the client’s language or fail to understand what is presented, the client will usually try again, but in the face of therapist inflexibility or being misunderstood, the client may subsequently drop out, lose interest or humor us by joining our world views or our therapist-centric mis-interpretations of the client’s reality. The client’s interactions, subtle or direct, verbal or non-verbal, hold meaning; further meaning is communicated through stated themes, action and resolution. We combine verbal and non-verbal information as best we can in order to understand what a client is experiencing and the meaning behind it.

I worked with a 1st grade boy many years ago who was referred for psychological assessment. I struggled at first to speak his language, as did most of the people who worked with him. He had unusual social skills (no friends, avoided eye contact, stayed to himself in the classroom), flat affect, hostile/angry interaction if challenged and did not follow directions. His teacher said he was mostly non-responsive and disengaged, meaning he did not answer her questions or respond to her requests and did not interact with other children.

I met with him several times and interviewed his mother. His non-verbal communication suggested a reticence or guardedness and his verbal communication lacked social reciprocity. I wondered if he might be on the autistic spectrum, but he did not speak in the manner of what we then called Asperger’s clients, nor did he engage in ritualistic or fixed behaviors. He seemed interpersonally avoidant or schizoid, which is somewhat unusual for a 1st grade child.

His mother was warm and effusive and fairly unconcerned about her son’s interpersonal and behavioral difficulties at school. She relayed that the child’s father had been depressed due to a job situation and got angry when he was in a bad mood. Her view was that her son was fooling others, especially women, because, “He pulls it over on them.” In her mind, he intentionally manipulated others to get them to leave him alone. She could not name any friends he had at home or school, and he was an only child. When asked about his angry responses to his teacher, she replied, “He’s not really like that. It’s all a game.”

I administered a test battery, and responses were atypical for a boy his age. I can picture his Kinetic Family Drawing even though this testing was over 20 years ago. The instructions were: “Please draw me a picture of your whole family, each family member doing something.”

He drew an artistically precise, finely detailed spaceship with little porthole windows, out of which arrows and projectiles were being launched. Each porthole was well armed. Explosions were taking place outside the spaceship. It took 30 minutes for him to complete the spaceship, after which he handed it to me and said, “Done.”

The drawing suggested paranoia and fear, self-protection, or perhaps a retaliatory “fight” response. I queried, “Thank you. I wonder if you could repeat the instructions for me.”

He replied, “You told me to draw my family. Each person doing something.”

“I see a spaceship,” I said. “Where is your family?”

With a look of disdain he pointed at the spaceship and said, “We’re in there! Who else do you think is firing the weapons?!”

OK. Fear and anger confirmed. Also, the drawing suggested that he and his family were isolated together inside the spaceship, protecting themselves from invaders or dangers. He refused to tell a story about the drawing other than to say it was a battle, and they were fighting it alone.

His language in this drawing was one of fear and self-protection. I commented, “Ah, I get it. You and your family are inside the spaceship guarding and protecting each other from the dangers. Space is a very dangerous place?”

“YES!” he said as he made first eye contact of the day.

His TAT stories were full of danger, anger and self-protection; they did not flow logically. He “lost track” of the story line as he described the pictures on the cards. He provided obsessive details about the means of protection and feared violence.

The Rorschach did not deter him, and he saw many things; however, a number of the things did not match reality. For example, “I see an Antler.” “Good,” I thought, a more typical response. “Show me the antler, where you see it and what makes it look like that.”

“Here it is. It is escaping. An Antler is a little like a deer. He shoots poison darts out of his eyes and you don’t want to get too close.”

That response was guarded and paranoid, and he had made up a new word with his unique meaning, a response more typical of psychotic individuals, and I had not seen a psychotic child before. I examined the rest of his responses, and there were several more neologisms (new words), tangential thinking and circumstantial reasoning provided with a matter-of-fact tone.

Buried in his language and stories (on the TAT and Rorschach) were subtle hints of trauma in the themes of danger, victimization and hypervigilance. I found symbols of coercion and force, and some possible sexual themes. I scheduled a risk assessment, with his mother present. When I asked if anyone had ever touched him on his body in a way that he didn’t like or made him do things to their body, he nodded his head. He pointed to his “butt” and “penis” and said he had been asked to do things to an older male. He did not display anxiety and was matter-of-fact in his detailed, accurate description of sexual abuse. I told the mother I believed that his anxiety about the abuse might be responsible for an acute psychotic reaction. His mother blanched and teared up. She agreed to take him for therapy for his trauma and also to go for a child psychiatric exam. The psychiatrist phoned me and thanked me for the interesting referral, saying, “He’s a weird kid, psychotic. I want to start medication.” With this opinion, the mother saw her son more clearly and started to come to grips with her son’s mental illness.

I had recognized that something was wrong after viewing his spaceship drawing, which communicated nonverbally quite a bit about his family, their isolation and need for protection. His dad’s angry behavior made him feel vulnerable, and the sexual abuse left him feeling alienated and alone. His “language” communicated fear and victimization through his stories and drawings, and it guided us in a new direction.

The point to be made here is that meaning could not be made until the boy was allowed to communicate in his own manner. The case outcome would have been different, for example, if only school-based social skills training had been done. I remain concerned about misdiagnosis due to inadequate information, and I believe that by adding art, play and stories to our protocols, we gain better understanding of our clients’ conceptual underpinnings.

I am not an Ericksonian play therapist per se, nor formally trained in that modality other than some workshops and extensive reading; however, I am a storyteller, and I recognize Erickson’s influence in my work. I am strengths based, use language sensitively and carefully, and metaphor, stories, art and play have turned out to be my most-used tools of the trade.

I have heard Dr. Jeff Zeig speak over the years, and he has talked fondly of spending much time with his mentor and friend Dr. Milton Erickson. He often tells the story of Erickson asking him something to the effect of (not a direct quote), “So Jeff, what is it that you do in therapy?” Jeff, wanting to impress, cited a number of theoretical and clinical influences and started telling Erickson what he had learned from them. Erickson stopped him and said something to the effect of (not a direct quote), “Jeff, I’m not asking what you do in therapy; rather, I’m asked what it is You-Jeff do in therapy. What is the Jeff style?” The emphasis on the You and not the Do changed the whole meaning and context of the question.