- 366 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

An Introduction to the Celtic Languages

About this book

This text provides a single-volume, single-author general introduction to the Celtic languages.

The first half of the book considers the historical background of the language group as a whole. There follows a discussion of the two main sub-groups of Celtic, Goidelic (comprising Irish, Scottish, Gaelic and Manx) and Brittonic (Welsh, Cornish and Breton) together with a detailed survey of one representative from each group, Irish and Welsh.

The second half considers a range of linguistic features which are often regarded as characteristic of Celtic: spelling systems, mutations, verbal nouns and word order.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

The historical background to the Celtic languages

1.0 Introduction

Speakers of the modern Celtic languages, Irish, Scottish Gaelic, Manx, Welsh and Breton, are today only to be found on the western seaboards of the British Isles and France. But they are inheritors of languages which some two thousand years ago were spoken throughout Europe and even in Asia Minor. It is, therefore, important and often useful to retain a historical perspective when considering the Celtic languages. The present volume attempts to provide a general introduction to the Celtic languages for linguists unfamiliar with them. The Celtic languages can seem very difficult and complex to non-Celticists and one good reason for adopting a more historical approach is to show that many of those complexities arose by a comprehensible process of historical development. For example, the phenomenon of the initial mutations which marks out Celtic languages, discussed in Chapter 7, can be shown to be the outcome of a series of reasonably well-understood historical developments, none of which would startle a historical linguist. It is beyond the scope of this volume to provide detailed discussion of every single aspect worthy of consideration, and there are inevitable omissions.1 However, the detailed bibliographical resources should provide the necessary back-up and support to enable the reader to broaden his or her knowledge in any area. Several multi-author volumes have appeared recently, MacAulay 1992a, Ball and Fife 1993 and Price 1992a, which offer discussions of the individual languages and also, in some, discussion of the earlier stages.2 Nevertheless, it is very difficult in such a format to maintain a consistency of approach and impossible to capture generalizations about Celtic languages as a group or to discuss common features.

The rest of Chapter 1 considers the Celtic languages in their IndoEuropean context with particular emphasis on the evidence for the early Celtic languages of Continental Europe. Chapters 2-5 concentrate on the two main groups of the Insular languages, Goidelic and Brittonic. Chapters 2 and 4 consider the historical development of the two groups, while 3 and 5 examine in detail a modern representative of each, namely Irish and Welsh respectively. The remaining chapters examine a number of general topics - writing systems, mutations, verbal nouns and word order - topics which are often regarded as containing features characteristic of Celtic.

1.1 Celtic as an Indo-European language

The Celtic languages belong to the Indo-European group of languages, members of which include Latin and the Romance languages, Greek, the Indo-Iranian languages (including Sanskrit, Avestan and Persian) Russian, German and English.3 Speakers of Indo-European languages can, therefore, be found from Iceland and the Hebrides to the mouth of the Ganges even before taking into account the historically more recent migrations to the Americas, Africa and the Antipodes. Even the most simple of lexical comparisons suggests a connection between these languages, e.g. OIr bráhir 'brother', Lat frãter, Gk phrā́tēr, Goth bropar (H. Lewis and Pedersen 1961: 6); OIr ech 'horse', Gaul Epona < *eku̯o-, cf. Lat equus, Gk híppos, Skt aśva (H. Lewis and Pedersen 1961: 3). The relationship between these languages, however, runs much more deeply than simple lexical correspondences. The Celtic languages show, for example, in various stages of disintegration, a nominal case system similar to that of the classical languages, with phonologically related elements, e.g. OIr eich 'horse' (gen. sg.) < *eku̯ī cf. Lat equī, OIr fiur 'man' (dat. sg.) < *u̯irū < *u̯īrō. cf. Lat virō, Gaul -oui, Gk -ōi: OIr feraib 'men' (dat. pl.) < *u̯irobis, cf. Lat -ibus, Gk -(o)phi, Skt -bhis; etc. (H. Lewis and Pedersen 1961: 166-7). Furthermore, they have a verbal system which, despite superficial dissimilarities, shares a number of features with the verbal systems of other Indo-European languages; for example, the alternation in Old Irish of berid: .beir 'he carries' < *bereti/beret seems to continue an alternation of endings also seen in Skt bharati: (a)bharat (McCone 1979a: 26-32). Old Irish also shares a reduplicated perfect or preterite formation with Latin, Greek and Indo-Iranian (McCone 1986: 233), and a reduplicated future with Indo-Iranian languages (McCone 1991a: 137-82; for further discussion, see 2.2.6 below).

1.2 Continental Celtic

The evidence for Celtic speaking peoples in Continental Europe is widespread but variable in quality and quantity.4 Our knowledge of the distribution of Celtic tribes is largely dependent on classical authors who portrayed the Celts as one of the barbarian tribes who threatened the peace and stability of the Mediterranean world (Rankin 1987: ch. 6). Their testimony can be misleading; use of the generic term Keltoi in Greek or Celtae in Latin does not necessarily refer to speakers of a Celtic language unless decisive personal names or local names are present. Much of our knowledge of Continental Celtic depends precisely on such evidence. Celtic names in Continental Europe are identifiable by the fact that they contain elements also found in the later languages; for example, Vercingetorix, the name of a Gaulish tribal leader, is divisible into three elements ver- 'over, above', cf. Ir for, OW guar, MnW gor; -cingeto-, cf. Ir cingid 'he steps, walks'; -rix, cf. Ir rí (gen. ríge), W rhi, Lat rēx, etc. (D. E. Evans 1967: 121-2); the name may thus be interpreted literally as 'the king who walks over' but should perhaps be taken as 'Super-champion' vel sim. (Hamp 1977-8: 12).5 The Gaulish personal name Curmisagios contains the elements curmi'beer', cf. Ir cuirm, W cwrw, and -sagios 'seeker', cf. Ir saigid 'he seeks', W haeddu and -hai 'one who seeks ...' (Ford and Hamp 1974-6: 155-7, Joseph 1987, Russell 1989: 38-9). The precise sense of the compound is unclear though the more legalistic 'beer-steward' is more complimentary than 'beer-seeker'.

A combination of ethnographers' accounts and the analysis of personal and local name elements allows us to identify the limits of Celtic tribal movements, at least in general terms.6 The high density of Celtic name elements in Gaul, northern Italy and Spain shows that these regions were largely, if not entirely, Celtic speaking in the pre-Roman period, but the ethnographers also record migrations into the Italian and Balkan peninsulas and even as far as Asia Minor (Rankin 1987: 45-102). In the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC, Celtic tribes migrated across the Hellespont and settled in Galatia in central Asia Minor (Rankin 1987: 188-207); the tribal name Tectosages and the place name Drunemeton (Strabo xii.5.1) 'oak-shrine' (compare Ir drú, W derw 'oak', and Ir nemed 'shrine, high noble', W nefed (Schmidt 1958)) testify to the Celticity of these immigrants (see Mitchell 1993: 11-58). The relationship between the languages of these different areas is discussed below (1.6). At present we may consider the evidence of these languages in more detail.

1.2.1 Gaul

The evidence of ethnography and naming practices can allow us to define limits, but within the major Celtic speaking areas of western Europe more evidence is available. Again much but not all the evidence is onomastic. The presence of a Greek colony at Massalia (Marseilles) made a writing system available to the inhabitants of southern Gaul even before the arrival of the Romans.7 There is a significant number of Gaulish inscriptions written in Greek script (see Lejeune 1985 and

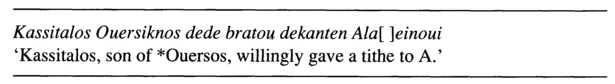

FIGURE 1.1 A Gallo-Greek inscription from southern Gaul. Lejeune 1985: G-206 (pp. 284-7).

6.2.1 below); most seem to date from between the 2nd and 1st centuries bc though some may be older. By far the majority of these 'GalloGreek' inscriptions are graffiti on fragments of pots and consist entirely of personal names. The stone inscriptions are fewer in number but often longer and more informative about the language. Most consist of dedications to divinities and, in addition to personal and divine names, contain several Gaulish phrases. Many are fragmentary but an almost complete example (given in Figure 1.1) shows the nature of the evidence. The phrase dede bratou dekanten has been convincingly interpreted as 'gave a tithe in gratitude' by Szemerényi (1974 and 1991), where dede represents a perfect 3rd singular corresponding in stem form to Latin dedit and dekanten is the accusative singular of a noun based on *dekan 'ten' (cf. Ir déc, W deg, Gk déka and Lat decem). The inscription also demonstrates a very common feature of Gaulish nomenclature, the use of a suffixed form of a personal name to mark a patronymic (Russell 1988a: 136-7), hence the uncertainty over the basic form of the name in the example in Figure 1.1. Whatever the correct form of the final divine name, it is in the dative case with an ending -oui.

However, by far the largest...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- List of abbreviations

- The periods of the Celtic languages

- 1 The Historical background to the Celtic Languages

- 2 The Goidelic languages

- 3 Irish

- 4 The Brittonic languages

- 5 Welsh

- 6 The orthographies of the Celtic languages

- 7 Lenition and mutations: phonetics, phonology and morphology

- 8 Verbal nouns, verbs and nouns

- 9 Word order in the Celtic languages

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access An Introduction to the Celtic Languages by Paul Russell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.