eBook - ePub

The Ottoman Turks

An Introductory History to 1923

Justin Mccarthy

This is a test

- 424 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Ottoman Turks

An Introductory History to 1923

Justin Mccarthy

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Justin McCarthy's introductory survey traces the whole history of the Ottoman Turks from their obscure beginnings in central Asia, through the establishment and rise of the Ottoman Empire to its collapse after World War One under the pressures of nationalism. Vividly illustrated with many maps, this introductory overview is designed for non-specialists but is written with great authority and with access to original sources. It fills an important gap for an authoritative but accessible account of the rise of one of the world's great civilizations.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Ottoman Turks by Justin Mccarthy in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Chapter 1 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Prologue: Origins of the Turks, to 1281

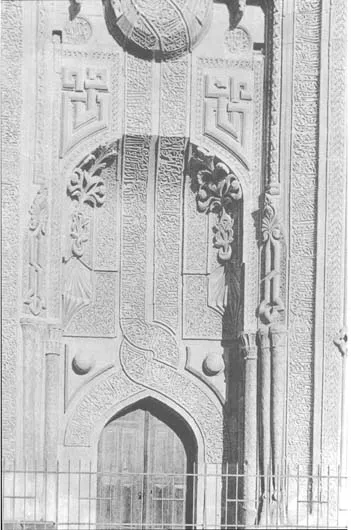

Overleaf

Door of the İnce Minare Medrese at Konya, built in 1260–65 by order of the vezir Sahib Ata. As Islamic rulers, the Rum Seljuks and their vezirs were patrons of Islamic architecture and culture. The building of medreses (Islamic schools) brought Islamic learning to Anatolia, cementing the Muslim character of the region and demonstrating the commitment of the rulers to orthodox Islam. (Turkey, General Directorate of Publications, Fotoǧrafla Türkiye, Ankara, 1930.)

Prologue: Origins of the Turks, to 1281

In the beginning of their recorded history Turks were nomads. Their original home was in Central Asia, in the vast grassland region that spreads north of Afghanistan and the Himalaya Mountains, west and northwest of China. By any normal standards of human comfort, Central Asia was a good place to leave. Its lands ranged from desert to forested mountains, but the general environment was bleak – high plains that were only slightly more attractive than desert for human habitation. Temperatures in winter could fall below − 34 °C (− 30 °F) and in summer rise to over 49 °C (120 °F). Average temperatures over most of the region, were below freezing in January, well over 27 °C (80 °F) in August. Spring was short, winter long, with snow covering the ground at an average depth of two and a half feet (75 cm) for almost half the year. Geographers classify some of the land as tundra, some as steppe.

The steppe grasses of their homeland best supported livestock and the Turks were primarily hunters and herdsmen. Because sheep devoured the grass in any one area fairly quickly, the Turks were forced to move from one pasturage to another in order to feed the flocks upon which they depended. Large groups would have quickly over-grazed the land and small groups could not defend themselves, so the earliest Turkish political units were tribes. Although the size of each tribe varied according to its environment and the success of its leadership, none could have been considered large or important.

Had the Turks remained solely in their tribes, they would have had little effect on w o r l d history, but they did not. When necessary the Turkish tribes proved able to cooperate. Out of mutual necessity they joined together for defence or conquest under strong leaders to form armies and ultimately empires. Accepting the overlordship of a strong leader (called ban or khan) meant that tribal feuds were diminished and the tribes could be organized for major conquests. The tribes remained as separate units, but they cooperated with one another. When united, the Turkish tribesmen were a formidable force. Turkish nomads were raised in harsh surroundings, taught from childhood the necessity of discipline and the use of weapons. Armed with bows and riding small steppe horses, they formed a swift light cavalry that could defeat more traditional standing armies with ‘hit and run’ tactics. Battling against the Chinese and others, the Turks very early created nomad ‘empires’ in central Asia and beyond.

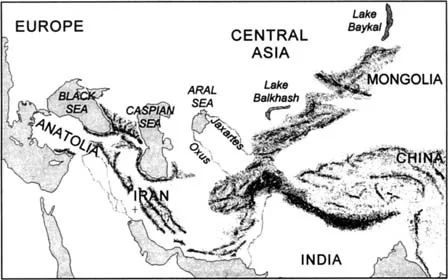

Central Asia and the Middle East.

The best known of these early confederations were the Huns, who threatened China from the third century B.C. As the Romans were defeating Hannibal and the Carthaginians in the Second Punic War, Turks were first invading China. Divided into different hordes and under different leaders, the Huns attacked both China and Iran in ensuing centuries. Under their leader Attila, known best in Europe for being persuaded (or bribed) by Pope Leo I to spare Rome in 452, Huns reached as far as Italy and France in the fifth century. Attila's empire extended through what today is southern Russia and the southern Ukraine, Romania, and much of Central Europe. In the sixth and seventh centuries a great Turkish empire, the Turkut, ruled from the Aral Sea to the borders of the Chinese empire and into Mongolia. In the eighth and ninth centuries the Uygur Turks ruled an empire south of Lake Baykal, superseded by other Turkish groups in the ensuing centuries throughout Central Asia.

The Turks were among the major waves of invaders who first attacked, then settled in the Middle East. There was a constant tension between the inhabitants of settled areas and the nomadic peoples of the steppes and deserts that surrounded the Middle East. Nomadic tribes were often peaceful trading partners of settled peoples. But in large numbers they were a threat to both rulers and farmers. If vast armies of nomads entered the Middle East from Central Asia, they could be expected to turn farm land into grass land to support their flocks, to the considerable detriment of those who had farmed the land. N o m a d raids would disrupt trade, damage farming, and generally harm the tax base upon which rulers depended. Nomads themselves did not pay taxes. Therefore, Middle Eastern rulers defended their borders against nomads. Nevertheless, nomad groups periodically succeeded in overwhelming the defences. After a period of upheaval, nomads settled down and their rulers became the new guardians of the Middle East against the next group of nomads.

The Arab Muslims who conquered the Sassanian Persian Empire in the seventh century extended their dominion into the borderlands of Central Asia, across the River Oxus into the region called Transoxania, the area between the Oxus (today the A m u Darya) and the Jaxartes (today the Syr Darya) rivers. There they came into contact with the Turks.

Under the Prophet Muhammad (c. 570–632) and his immediate successors, Arabia had been unified under the rule of Islam. The religious and political descendants of Muhammad had then taken lands from North Africa to the borders of Central Asia. During the rule of the Umayyad Caliphs (661–750), Arab armies had conquered Transoxania. The Abbasid Caliphate, which succeeded the Umayyad Caliphate in 750, cemented Islamic rule from western India to the Atlantic Ocean in a vast empire. No other state of the time could compare to it. Charlemagne (ruled 771–814) and the Abbasid Caliph Harun al-Rashid (ruled 786–809) of Arabian Nights fame both ruled at the same time, but the area of Charlemagne's empire would have fitted many times over into Harun's Caliphate. Moreover, the Frankish standards of learning and commerce were considerably lower than those of the Abbasid Caliphate. The bastion of the Abbasid Caliphal Empire in the east was in Khurasan (northeastern Iran) and Transoxania. In the eighth to ninth centuries, Islam became the majority religion in Iran and Transoxania, which was a cultural and economic extension of the Iranian world. Transoxania became a centre of Muslim religion, administration, and culture. Samarkand and Bukhara, the great cities of the region, became major economic centres, profiting from their position on the main routes of East-West trade. All the trappings of Muslim culture were to be found in them – great mosques, schools, charitable institutions, and the organs of Middle Eastern government. The traditions of Islam and pre-Islamic Persia mixed there, creating a high civilization at a time when the empire of Charlemagne had disintegrated, vikings raided, and much of Europe had descended into near-anarchy.

The Turks of Central Asia came into contact with the civilization of Transoxania through trade and warfare. Although nominally a province of the Abbasid Caliphate, the region was in fact ruled by a dynasty of Persian Muslims, the Samanids, from 875–999. The Samanid rulers expanded their rule and raided into Central Asia, across the River Jaxartes, coming into close contact with the Turks. Other Turks contacted the Samanid dominions through merchant enterprises or as slaves, captured and taken back to the Middle East. The contact also went the other way, into Central Asia. Muslim merchants from Transoxania and beyond traded in Central Asia itself. Nomadic Turks could see that the Middle East had many things they did not, especially riches. But it was Muslim missionaries who had the greatest effect on the Turks.

The Turks and Islam

The life of the Turks was greatly affected by communication with the Arab Muslims and with Persians who had converted to Islam. The Turks were not complete strangers to monotheistic religion, since a significant number had converted to Nestorian Christianity, which had been spread throughout Central Asia by missionaries. Turks had also become Buddhists. Judaism had been the official religion of one large group of Turks, the Khazars. However, the greatest number of Turks followed what has been described as a ‘shamanistic’ religion. The Turks, led by holy men, or shamans, worshipped or propitiated elemental forces of nature, believing that spirits lived among them in the earth and the skies. The spirits could be dangerous and needed to be appeased. Animals such as the wolf or bear were taken as totems. Nevertheless, over all the gods or natural forces was the one supreme God, Tanrι, who lived in the highest heavens. When they died, those who were moral went to a heaven, thought to be in the sky. Those who were evil went to a hell, under the earth. From early times, the Turks also were concerned with what can be called mystical religion, a desire for personal contact with the Divine that included ecstatic religious practice. They also showed reverence for holy men, alive and dead, who were felt to be close to God.

The basic understanding of one most powerful God and some experience with Christianity may have predisposed the Turks to accept Islam easily. Although it was much more sophisticated than the nomads' religion, Islam also held that there existed one supreme being, a heaven, and a hell. It accepted the presence of a sort of spirit, the jinn (or genies), who coexisted with man. Islam did not accept the propitiation of spirits or many of the other Turkish religious habits, but there were enough similarities in basic belief to make Islamic monotheism attractive to the Turks.

Islam and the central Asian Turks

Islam was a religion concerned with rules that governed the lives of its adherents, as well as with salvation, prayer, and spiritual growth. The normal path to salvation was through membership in the Islamic community and obedience to its rules. The Holy Law of Islam, the Sharī‘ah, which was drawn from the Muslim Holy Book, the Quran, and the sayings (Ḥadīth) and practices (Sunnah) of the Prophet Muhammad, was to govern all human endeavour. Islamic scholars and judges applied the Holy Law to all aspects of life. Islam can thus be called a religion of laws. Despite the attractive power of monotheism and Law, it is easy to see that the restrictions of Islam might have made conversion to Islam difficult for nomads of the steppe. The nomads had their own laws, their own traditions of authority, shamanistic beliefs, and a proclivity for mystical religion – all of which might have come into conflict with orthodox Islam. However, Islam showed a practical tolerance for the beliefs of new converts, expecting the descendants of the converts to become gradually more orthodox as generations passed. Moreover, the Muslim missionaries who converted the Turks were themselves not always orthodox. Conversion of the heathen in an uncomfortable and dangerous region such as Central Asia appealed more to heterodox zealots than to the theologically conservative. The missionaries often accepted more ecstatic religious experiences and practices than did the more Law-minded orthodox Muslims.

The new converts were allowed latitude in their religious beliefs, keeping much of their reverence for their saintly ancestors as well as certain shamanistic practices. It is doubtful if they were much bothered by questions of theology. The full panoply of Islamic Law only gradually applied to them. In particular, many Turks kept their mystical orientation. Turkish Muslims showed a desire to extend religion beyond the realm of Islamic legalities into mystical communion with God. Mysticism remained a basic part of Turkish religion, and in time this mystical orientation was even recognized by the Islamic religious establishment as being a legitimate, if always somewhat suspect, part of true religion.

Islam proved to be an opening for the Turks into the Middle East. Because it was a religion that stressed the community of believers over ethnic or linguistic differences, Islam accepted the Turks as brothers upon their conversion. They advanced from a position of outsiders into one of religious brotherhood. Their entry into the Middle East and integration into Middle Eastern Islamic culture and society was thus facilitated.

Turks had already come into contact with the Middle East though trade. The ancient Silk Road between the Middle East and China passed through Turkish lands. Turks were especially integrated into the economy of the borderland province of Muslim Transoxania, trading in the great cities of Samarkand and Bukhara. One trade proved to be especially important in bringing Turks into the Middle East, the slave trade. Muslim rulers bought or captured Turkish warriors and made them slave-soldiers in the Abbasid Caliphate, the great Muslim empire that began in 750, and in other Muslim states. Converts to Islam, these Turks often rose to high position, sometimes even usurping the power of the Caliph. Nevertheless, their numbers were relatively small. The great mass of Turks in Central Asia were outsiders to the Middle East until they embraced Islam.

Once the Turks became Muslims, Middle Eastern rulers were more readily able to use them as they might use any other group of Muslim troops, as mercenaries. By the tenth century the Islamic Empire was breaking into small units, each accepting the rule of the Caliph in theory, but actually independent. In eastern Iran, Muslim rulers and governors hired confederations of Turkish tribes to fight on their behalf. Once the Turks realized they held the balance of power they took charge themselves. One of these groups, the Ghaznavids, took Afghanistan, part of eastern Iran, and much of India. Another, the Seljuks, moved to the west.

The Seljuks

In the tenth century a large group of Turks known as the Oguz inhabited the region of Central Asia north of Lake Balkhash. One clan of the Ogu...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Dedication

- 1. Prologue: Origins of the Turks, to 1281

- 2. The First Ottomans, 1281–1446

- 3. The Ottoman Classical Age, 1446–1566

- 4. The Ottoman State

- 5. Destabilization, 1566–1789

- 6. Imperialism and Nationalism

- 7. Environment and Life

- 8. Turkish Society and Personal Life

- 9. Reform, 1789–1912

- 10. The Human Disaster

- 11. The Great War, 1912–18

- 12. Revival, 1918–23

- Glossary

- Index