This is a test

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Place of Geography

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The Place of Geography is designed to provide a readable and yet challenging account of the emergence of gepgraphy as an academic discipline. It has three particular aims: it seeks to trace the development of geography back to its formal roots in classical antiquity; provides an interpretation of the changes that have taken place in geographical practice within the context of Jurgen Haberma's critical theory; and thirdly, describes how the increasing separation of geography into physical and human parts has been detrimental to our understanding of critical issues concerning the relationship between people and environment.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Place of Geography by Tim Unwin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

CHAPTER 1

Geography: the social construction of a discipline

Geography should be encouraged to seize the central fortress, ejecting both pure science and that grossly over-promoted intellectual exercise called mathematics. Geography should stand alone with its one educational equal, the study of the human spirit in English language and literature. Geography is queen of the sciences, parent to chemistry, geology, physics and biology, parent also to history and economics. Without a clear grounding in the known characteristics of the earth, the physical sciences are mere game playing, the social sciences mere ideology.

(Leader in The Times, 7th June 1990: 13)

Geography is one of the oldest forms of intellectual enquiry, and yet there is little agreement among professional geographers as to what the discipline actually is, or even what it should be. Moreover, what has been practised as geography has changed substantially over the last two millennia. In recent decades the pace of this change has accelerated dramatically. One result of this is that the public image of what it is that geographers spend their time doing is often at considerable variance from reality. This book is about the causes of such changes, and the way in which an academic discipline is integrated into the society of which it is a part. In particular it addresses how specific societies produce knowledge. It suggests that what a society accepts as being truthful statements are the result of a series of interactions between social, political, economic and ideological interests. More formally, it is designed as a historically oriented reflection on the emergence of contemporary geography, which seeks to reveal the underlying connec tions that exist between knowledge, power and human interest.

In contrast to the fervent espousal of the importance of geography expressed within the quotation which opens this chapter, the discipline is not widely seen as forming an important element of the world's educational systems. Moreover, even in Britain where geography has for long been one of the most popular subjects at the secondary level, professional geographers play a very limited role in influencing political decisions. This is surprising given the wealth of research by geographers on subjects such as environmental monitoring, economic restructuring and climatic change, which are all currently seen as being politically sensitive. There would therefore seem to be some kind of discontinuity between the views society holds about the discipline as a subject to be taught at school and society's response to the way in which the discipline is practised by people claiming to be professional geogra phers.

In the last resort, academic disciplines exist not only because their practitioners believe in their validity, but also because the societies of which they are a part believe in their utility. Both teaching and research are expensive, and, particularly during times of economic recession, the content of both therefore reflects a process of negotiation between academics and the society in which they live. However, the public image of geography should also bear some resemblance to what it is that people who call themselves geographers do. It is at this juncture that the present book takes its departure, first by examining what the public image of the subject is, and then by looking in more detail at the ways in which disciplines are defined.

1.1 Geography in the public domain

In The geographer at work, one of the few books designed to introduce geography to the wider public domain, Peter Gould (1985: xiv-xv) suggests that 'Most people have little idea what modern geography is all about.' His book begins with a description of a cocktail party at which the following conversation took place (Gould, 1985: 4):

'And what do you do?' she said.

'Oh,' I said, grateful for the usual filler, 'I'm a geographer.' And even as I said it, I felt the safe ground turning into the familiar quagmire. She did not have to ask the next question, but she did anyway.

'A geographer?'

'Er ... yes, a geographer,' said with that quietly enthusiastic confidence that trips so easily from the tongues of doctors, engineers, airline pilots, truckers, sailors and tramps...

'Oh really, a geographer ... and what do geographers do?'

He continues: 'It has happened many times, and it seldom gets better. That awful feeling of desperate foolishness when you, a professional geographer, find yourself incapable of explaining simply and shortly to others what you really do' (Gould, 1985: 4).

This account is typical of the experiences of many professional geographers, and well illustrates that the public understanding of what it is that geographers do is extremely limited. Such a situation cannot, though, be blamed on the public in general; geographers themselves have frequently been very poor at actually explaining and justifying their role in society. Indeed, many people teaching and undertaking research in geography departments when faced with the cocktail party question noted above, quickly cover their tracks, with statements such as 'Well, I'm really a soil scientist' or, 'Actually, I'm a consultant on development issues.' It is not easy to establish precisely why this is, but it is probably partly because such geographers realize that the public perception of the discipline is so far removed from their everyday practice that to say simply that they were geographers would appear relatively meaningless. It may also be because geography is such a wide ranging discipline, covering research on topics as diverse as mountain forming processes and the medieval wine trade, that the single word geography conveys little idea of precisely what sort of research is undertaken by geographers. One cannot, though, escape the conclusion that it may also be because many people working in geography departments remain unhappy with the idea that there is indeed some thing unique and worth while about their own discipline.

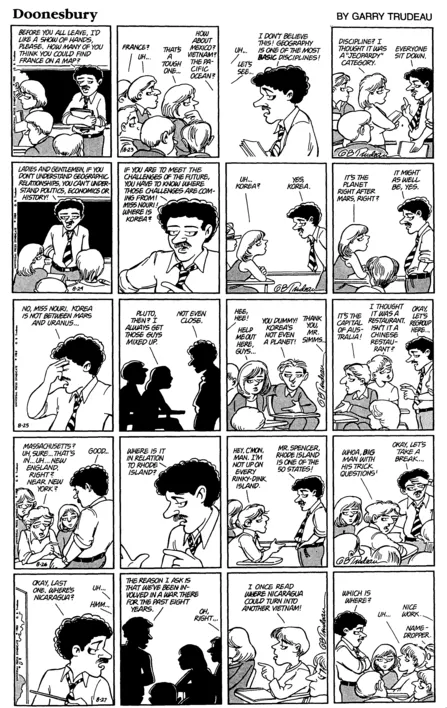

The image of geography held by most people is usually derived from their school education. Geography in Britain is thus still widely seen as being about 'capes and bays', and in the United States of America as being concerned with 'states and capitals'. This is well illustrated in a sequence of cartoons by Garry Troudeau (Fig. 1.1), depicting a teacher, clearly a dedicated enthusiast for geography as 'one of the most basic disciplines', asking his pupils to point out the locations of a number of places in different parts of the world (The Guardian, 23-27 August 1988). The students, in response, show little knowledge, even though the teacher points out that the reason he asked them to identify Nicaragua was that 'we've been involved in a war there for the past eight years'. This cartoon is particularly significant, because even if geography really is about 'capes and bays' or 'states and capitals', it suggests that the subject is evidently failing to provide students with a body of knowledge that they consider to be useful and worth remembering.

In the political sphere, geographers have played a very limited role in influencing decision making and in advising governments at national, let alone international, levels. Likewise, although the media coverage of geography is beginning to increase, geographers are still rarely inter viewed on news or current affairs programmes. In contrast, economists are widely asked for advice concerning the handling of the economy, and botanists are turned to for the development of new high-yielding varieties of crop to increase global food production. This situation was well illustrated several years ago during a visit to the headquarters of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations in Rome. The opportunity arose to discuss the potential contribution of research by geographers on the problems and implementation of agricultural development in the poorer countries of the world, and time and again the conversation would come around to the point that geographers had few immediately apparent skills or attributes which were perceived to be of use. Instead the FAO is keen to employ forestry experts, biochemists with specific skills in the development of pesti cides, and economists to undertake cost benefit analyses of the effects of introducing certain types of innovation. This is not to deny that some

Fig. 1.1 Doonesbury by Garry Trudeau (The Guardian, August 1988). Universal Press Syndicate © 1988 G.B. Trudeau.

geographers have played a significant part in influencing policy decisions (for example Hall, 1963, 1980, 1988), but it is to suggest that their role is less than that of practitioners in some other disciplines. In part this reflects the widespread separation between the realms of political decision making and academia in general, but it also illustrates that there is no immediate vocational niche for geographers.

Another way of examining public attitudes concerning the value of geography is to look at employers' opinions of geography graduates. A survey undertaken in the mid-1980s (Unwin, 1986), for example, suggested that while no employers saw a geography degree as being a distinct handicap, at least half of the respondents saw it as offering no particular advantages. Of the employers who did see a geographical training as being useful, the majority thought that it was the computing and statistical skills provided in geography degrees that were of most importance. Another more alarming conclusion from this survey was that most employers had little idea about the sorts of teaching and research that were being undertaken within geography departments in Britain during the 1980s. Although this may also be true of other disciplines, given that employers tend to be more concerned with the personal attributes of applicants than with their academic achievements (Unwin, 1986), this once again reflects the poor performance of geogra phers in developing public awareness about their discipline.

In most countries, questions of public awareness and accountability are central to debates over the future shape of higher education. Although inertia and vested interests make it difficult to change the organizational framework of disciplines, recent experiences in Britain at least, suggest that governments can, through their role as paymasters, have a very significant influence on the type of teaching and research practised in institutions of higher education (for an Australian compari son see Powell, 1990). If specific disciplines are not seen to be providing either useful graduates or useful research, then, particularly during times of financial stringency, the amount of funding that they receive is likely to be reduced. This raises at least two fundamental issues. First, it assumes that it is indeed possible to distinguish between particular types of knowledge that are, and are not, useful. Secondly, though, it also requires the formulation of clear criteria by which disciplines can be identified.

1.2 The construction of disciplines

Despite the institutional factors giving rise to the apparent immutability of contemporary disciplinary boundaries, there is nothing absolute or sacred about them; all disciplines have been created and argued over by people, and there is no single criterion upon which such boundaries can be agreed. In general terms, disciplines have been identified and justified in four main ways.

First, it has been argued quite simply that a discipline is the collective activity of its practitioners; geography can thus be seen as being whatever it is that geographers choose to do. Bird (1989: 214), for example, advocates that 'geography is what geographers have done; geography is what geographers strive to accomplish'. It is this type of usage, referring to activity within the discipline, that Johnston (1986a) calls academic. Such a definition emphasizes that disciplines are social phenomena that reflect the institutional and political frameworks within which they emerge. Geography departments exist in universities and polytechnics, and the staff within them have to compete for resource allocations in order to maintain their collective existence. Accordingly, geographers must continue to attract undergraduate and postgraduate students, by teaching something called geography that is seen as having some interest or utility to those who study it. They must do research that their financial sponsors deem to be useful. Changes are brought about by the activities of influential groups of people within the discipline. Success is achieved through the propagation of a beneficial image of the discipline within society; failure results from an inability to produce useful products.

A second way in which attempts have been made to identify individ ual disciplines has been through reference to particular objects of study or subject matter. It is this usage that Johnston (1986a) terms the vernacular. Such definitions suggest that there are certain objects that are geographical, and that are not, for example, social or geological. This implies that some specific order exists in the world of phenomena, within which practitioners of any discipline simply need to identify their niche. Competition then exists between disciplines for particular objects, with successful disciplines expanding at the edges and swallow ing up less successful ones. In general this is the system of definition and justification that is most often resorted to (Holt-Jensen, 1988), and can be exemplified by much geographical work in the first half of the 20th century on the region. Geographers such as Fenneman (1919) thus saw the region as being their particular object of study, arguing that its use would serve to prevent geography from being absorbed by other sciences.

Thirdly, disciplines have also been described in terms of their meth odology or techniques. Mentions of historical methods (Bloch, 1954; Norton, 1984; Driver, 1988) and geographical or geomorphological techniques (Ebdon, 1977; Silk, 1979; Clark, Gregory and Gurnell, 1987a; Goudie, 1990) are thus widespread, and many geography undergradu ate degree programmes have courses that incorporate phrases such as 'geographical methods and techniques'. Again, as with subject matter definitions, such justifications attempt to delimit disciplinary bound aries with reference to a unique set of technical tools, that can be learnt and applied to different phenomena. Disciplines thus expand through the creation of new types of technique, or through the poaching and development of methods from other disciplines. A classic current example of this practice has been the rapid development of so-called geographical information systems, and the spate of lectureships in this subfield of the discipline that were advertised in Britain during the late 1980s (Chrisman et al., 1989; Maguire, Goodchild and Rhind, 1991).

Both subject matter and methodological definitions tend to imply a static and unchanging view of the academic world, built upon the justification that there really are methods and techniques that can create specific single disciplines. One thus becomes a geographer by learning a particular set of skills and subjects that comprise some kind of geographical truth. A fourth way of defining disciplines attempts to avoid such a replicative stance, by focusing on the sorts of questions that disciplines ask, and the ways in which these questions are framed. Although such definitions again seek to divide up the realm of academia into distinct cells, disciplines defined on the basis of the questions that their practitioners ask can no longer remain stagnant and unchanging.

For the majority of people, the content of any particular discipline does not, though, depend on a well-formulated theoretical debate, but rather on their practical experiences of it in the classroom. It is therefore particularly important to examine the connections between geography as it is practised at different levels within the educational system. This is significant not only for understanding the wider public image of the discipline, but also for examining the type of teaching and research activity within it.

1.3 Geographical education

Gritzner (1986: 252) has suggested that,

No building or field of knowledge is stronger than its foundation; the 'temple' of academic geography rests upon the geographic knowledge and skills possessed by the products of the nation's elementary and secondary schools and the students who, both quantitatively and qualitatively, ultimately enroll in our own courses.

Such experiences, though, vary greatly, not only between countries, but also within a single country depending on the type of syllabus followed. Indeed, the amount of geography studied at the primary and secondary levels can vary from almost none, as in much of the United States of America, to about one-third of the curriculum for those doing A-level geography in England and Wales. In most Euro pean countries, the required amount of geography varies somewhere between these two extremes. Broadly speaking, it is possible to categorize educational systems into those that maintain a breadth of subjects throughout the primary and secondary curriculum, as in much of Europe, and those that allow considerable specialization, as currently in England and Wales where those in the last two years of their secondary education can specialize in as few as two or three subjects. The contrasts between the role of secondary geography in the United States of America and in England pro...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter 1 Geography: the social construction of a discipline

- Chapter 2 The place of theory

- Chapter 3 Geography and society: classical context and a world of discovery

- Chapter 4 The emergence of geography as a formal academic discipline

- Chapter 5 From region to process: the emergence of geography as an empirical-analytic science

- Chapter 6 Geography and historical—hermeneutic science: the quest for understanding

- Chapter 7 Critical science and society: the geographer's interest

- Chapter 8 The place of geography

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index