Cynthia D. Belar and Tricia L. Park

In contrast to traditional psychological assessment which focuses on personality and defense mechanisms for the purpose of treatment of mental health problems, psychological assessment in the medical setting involves the integration of information regarding cognitive, affective and behavioral functioning vis à vis physiological health, illness and disability. While seemingly broad in nature, health psychology assessment is necessarily focal, driven by the clinical question and context of the assessment. Although an integral component in the design of psychological treatments, a major use of this specific type of assessment is to solve problems for other health professionals in providing care for their patients. Thus, consultation activities are often an integral part of the assessment process.

The assessment issues addressed in the present chapter are relevant for health promotion, primary and secondary prevention, tertiary care, and rehabilitation. Assessment recipients include the normal population undergoing risk assessment, the “worried well” seeking to promote health, and identified patients in both acute and chronic phases of illness or injury/disability. As noted elsewhere (e.g., Belar, 1997; Belar & Deardorff, 1995), there are many purposes of assessment, including differential diagnosis, treatment planning, and outcome assessment. For example, specific assessment can help clarify diagnostic issues associated with: (a) psychological presentations of organic disease (e.g., depression in hypothyroidism, delusional thinking in HIV+ dementia); (b) psychological problems secondary to disease (e.g., post cardiotomy delirium, body image problems subsequent to amputation, post myocardial infarction depression, post-traumatic stress disorder resulting from accidental burn); (c) somatic effects of psychological distress (e.g., angina, headache, decreased pain tolerance); and (d) somatic presentations of psychological disorder (e.g., masked depression, somatization, chest pain in panic attack).

Assessment for treatment planning includes that associated with the treatment of psychophysiological disorders, interventions for psychological reactions to illness/disability, cessation of deleterious health habits, and development of health-promoting behaviors. Assessment is also used in planning psychological interventions that have been successful in producing changes in actual physical symptoms (e.g., vasospasms) and health status indicators such as length of hospital stay.

It is important to emphasize that in addition to planning for psychological interventions, psychological assessment is as important for the planning of many medical, surgical and rehabilitative treatments. Many clinical health psychologists provide assessments related to readiness for treatment such as organ transplantation, competence to make decisions regarding termination of life support systems, informed consent for participation in elective procedures such as oocyte donation, and issues of adherence to medical regimens. Clinical health psychology assessment is used post-treatment to identify progress with respect to intervention targets, and to assess sequelae of various medical-surgical treatments.

Psychologists who use assessment in medical treatment planning often work as a member of a multidisciplinary team, providing case-centered consultation as well as leadership in team-building processes. Thus another use of assessment is to understand problems of health care providers and health care systems, with a focus on such issues as provider-patient relationships, staff burnout, design of delivery systems and organizational culture.

Clinical health psychology assessment can occur in a variety of settings, e.g., private practice office, emergency room, inpatient unit, out-patient clinic, primary care setting, tertiary care center, rehabilitation hospital, nursing home, or patient’s home. Population assessments often occur in public settings such as shopping malls, exercise centers and community facilities. However, this chapter will focus primarily on assessment of patients in clinical settings.

No one clinical health psychologist has expertise in each and every area of possible practice. The kinds of assessments conducted will be determined by the characteristics of the clinical problems addressed and the nature of the referral sources. Thus training of referral sources is an important part of practice. To facilitate the health psychologists’ learning, we provide with materials that describe both criteria for referral and examples of physician-patient communications that can facilitate the referral process.

In brief, clinical health psychology assessment involves evaluating assessment needs, choosing appropriate methods, gathering information, formulating impressions, and concisely communicating results. The remainder of this chapter will describe a particular model for understanding the assessment needs of patients, discuss methods of data collection, address issues in case conceptualization and communication of results, and examine specific pitfalls to be avoided in the process. The attempt is to be comprehensive, but not exhaustive in scope.

A model for assessment

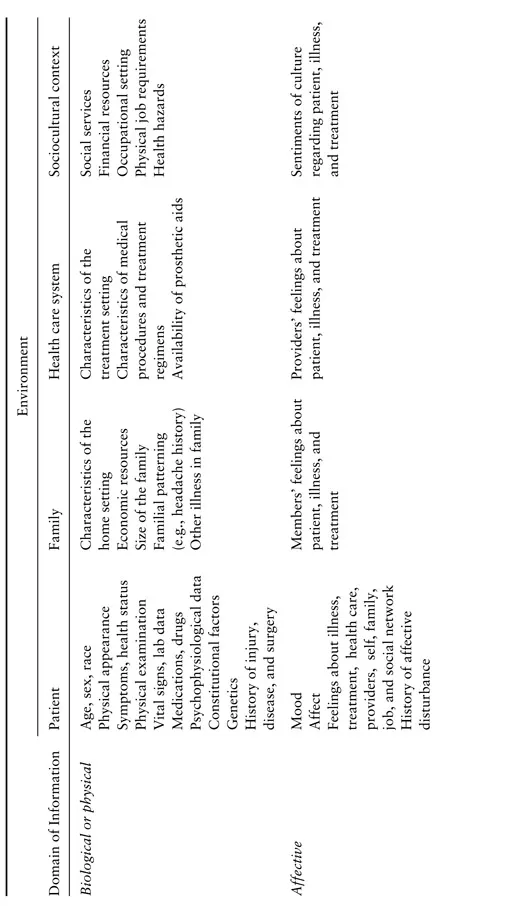

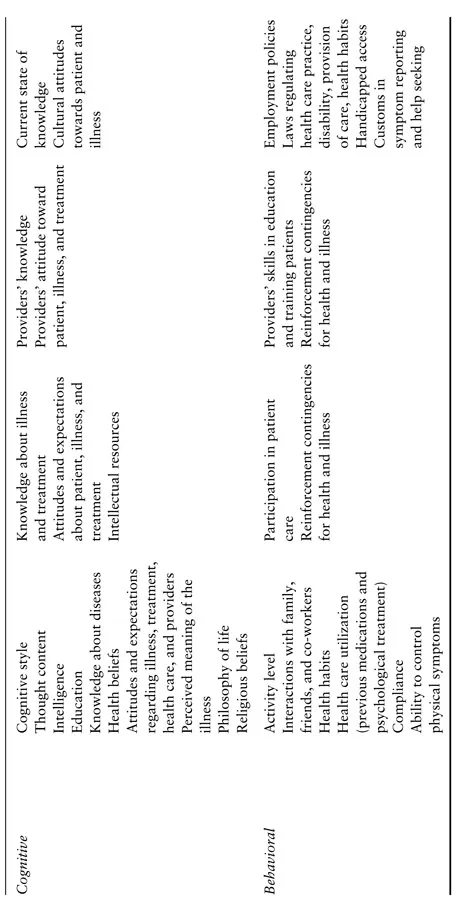

Clinical health psychology assessment varies widely depending on the referral question, patient status, illness/disability, referral source, and treatment setting. For case conceptualization and treatment planning purposes, it is useful to have a model to help direct assessment efforts and to ensure a thorough appraisal of pertinent medical, biological, psychological, and social information. In earlier work (Belar et al., 1987), the senior author proposed a model based on an extension of work by Engel (1977) and Leigh and Reiser (1980) who advocate for a biopsychosocial model in health care. Our model articulates targets of assessment by domain of information (biological or physical, affective, cognitive, behavioral) and unit of assessment or source of data (patient, family environment, health care system and sociocultural context), all of which are the building blocks of the assessment process (see Table 1.1). Each block also has a developmental and historical perspective.

Although portrayed as categorical blocks of information, information in these blocks is interrelated in complex ways and we encourage the reader not to think in a compartmentalized fashion when evaluating its meaningfulness. This model is appropriate for the assessment of any clinical problem, although depending on the issues addressed, some blocks may be more pertinent than others. While it is briefly summarized below, other chapters in this text provide greater detail about specific content and methods pertinent to selected clinical problems or issues.

Biological Targets

Basic biological parameters such as age, gender, and race have immediate and long-term implications for medical and psychological care. Rozensky et al. (1997) underscore the need to consider life stage in the assessment of medical patients, particularly in terms of understanding the impact of chronic illness on interpersonal relationships, independence and dependence, body image, existential concerns, and goals

Table 1.1. Targets of Assessment

(p. 67). The psychologist also seeks to understand the potential impact on behavior of ongoing medical problems and their treatments (e.g., uremia associated with kidney failure, impact of high dose corticosteroids). With this information the clinician can more sensitively tailor the assessment as well as better understand the patient’s current presentation. Clinicians also need to know about previous illnesses, injuries, surgeries, number and length of hospitalizations, plus history of substance use.

Research has found many sociodemographic factors to be pertinent to a number of psychological assessment issues (Robinson & Klesges, 1997; Rodrigue, 1997; Weidner et al., 1997). For example, geriatric patients often present with decreased visual/auditory acuity, as well as slowed information processing and response speed (Andersen & Haley, 1997). Varying behavior and attention patterns of males and females with insulin dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM) may be explained by differences in glycemic control (Eriksson & Rosenquist, 1993; La Greca et al., 1995). Verbal fluency and manual dexterity have been shown to vary by age and gender (Benton et al., 1983; Bornstein, 1985). Moreover, race has been demonstrated to have significant relationships with physiologic and behavioral risk factors as well as health care utilization and access (Raczynski & Lewis, 1992).

Potentially crucial to the emerging clinical picture are data from the physician’s examination and laboratory assessments. Although technical in nature and sometimes difficult to interpret without consultation, this information can enhance the clinician’s understanding of the quality and severity of a patient’s past or present medical problem(s), including factors that may affect the behavioral presentation. According to Piotrowski and Lubin (1990), nearly half of clinical health psychologists surveyed utilized such data in the assessment process.

Finally, it may also be important to gather psychophysiological data such as electromyographic levels for tension headache and polysomnography for sleep disorders.

Affective Targets

Critical in the evaluation of medical patients is the assessment of current emotional status as well as patients’ feelings about illness, health care, family, friends, anticipated future and, of course, self. However, equally important is material pertaining to a patient’s past emotional functioning, both in general and under conditions of stress. In gathering information about affect, it is important to consider the timing, context, and sources of information. When assessing affect in inpatients, it is naive to believe that a one-shot consultation, often requested at a time of crisis, can reveal the more stable clinical picture. Repeat visits are often required.

Cognitive Targets

In assessing cognitive aspects, the clinician focuses on thoughts, beliefs, and attitudes as well as intellectual capacity. Intellectual, memory, and language tests are often used to elicit information about information processing style and capacity. To interpret findings, consideration of both medical and affective status is imperative since these factors can directly affect motivation and functional ability.

In addition to estimating patients’ intellectual capacity and ability to comprehend medical terminology and concepts, patients’ knowledge of their own disease should be understood. An analysis of these factors can promote an understanding of problems in adherence to medical regimens and suggest relevant interventions. For example, a highly anxious surgical patient with a low verbal intelligence may benefit from recommendations highlighting the need for concrete/simplistic language, repetition of information, visual presentations, and follow-up contacts for questions. While seemingly rudimentary in nature, such interventions may facilitate physician/patient communication as well as promote quality of care.

Clinical health psychologists also consider patients’ guiding philosophies in the areas of health (e.g., their specific health belief model), personal relationships, medical care, and world view, including religious beliefs. For those coming from different cultural backgrounds it is important to assess degree of acculturation. This information can help clarify current functioning, health behaviors, compliance patterns, and relationships with medical staff.

Behavioral Targets

Clinicians strive to understand patients’ overall behavioral patterns in areas of interpersonal, occupational, and recreational functioning. Focal targets include self-care and behaviors related to the reason for referral, including interactions with health care providers. Of special interest is whether the patient can exert voluntary control over any physical symptoms.

Integral to assessment of behavioral targets is information about lifestyle behaviors (e.g., use of alcohol, drugs, and tobacco; dietary habits; exercise patterns), health promoting behaviors (e.g., sleep, use of vitamins and relaxation methods) and illness-specific behaviors (e.g., adherence to medical regimens, health care utilization patterns). Rewards and consequences and existing contingencies in the various domains of functioning (e.g., home, work, doctor’s office, hospital) are also carefully weighed. Given that future behavior is often predicted by past behavior, inquiry about past hospitalizations, response to illness, and ability to cope with illness and treatment is necessary.

Environmental Targets

To complete a biopsychosocial assessment, the psychologist must understand the various environments within which the patient functions: (1) the family unit; (2) the health care system; and (3) his or her sociocultural context. Psychologists must also assess the demands, limitations, and supports that these environments provide in the physical, affective, cognitive and behavioral domains of functioning.

(1). Family environment. Information pertaining to role functioning and the dynamics of intra-familial relationships should be obtained, with special inquiry concerning changes in family roles from illness onset and the role of each family member with respect to the patient’s illness. Obtaining developmental history about the patient and family, the birth of children, major stressors, and family reactions can help clarify these issues.

Also vital is consideration of family members’ feelings about a patient’s illness, limitations, and treatment in the context of their understanding and attitude regarding the specific health issue. It is crucial to screen for beliefs and behaviors that may impair a patient’s recovery or prevent institution of healthy lifestyles (e.g., overprotectiveness, secondary smoke). Additional areas for exploration are more concrete aspects of the home environment, including available financial resources and perhaps physical characteristics of the home (e.g., accessibility), depending upon the problem being assessed.

(2). Health care environment. Before proceeding with an evaluation in the hospital setting, examination of environmental characteristics such as room size and privacy level, noisiness, and level of care is recommended so that special accommodations for interview or testing can be anticipated. Particularly important in working with the chronically and/or severely ill is an understanding of environments which in and of themselves can affect physical and emotional features (e.g., the doctor’s office and “white coat hypertension”, a bone marrow transplant unit and feelings of isolation). One must have knowledge of the nature of various medical procedures and the special issues associated with various health care sites.

The clinician must also pay attention to the quantity and quality of the interactions between patients and staff. Patient care can be jeopardized by staff attitudes, beliefs and behaviors that are influenced by worry or limited understanding and skill. For example, staff may silently fear working with persons who are HIV+. Unique st...