- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This series of volumes is dedicated to furthering the development of psychology as a branch of ecological science. In its broadest sense, ecology is a multidisciplinary approach to the study of living systems, their environ m ents, and the reciprocity that has evolved between the two. The purpose of this series is to form a useful collection, a resource, for people who wish to learn about ecological psychology and for those who wish to contribute to its development. The series will include original research, collected papers, reports of conferences and symposia, theoretical monographs, technical handbooks, and works from the many disciplines relevant to ecological psychology.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

II | ORDER IN BEHAVIOR AND EVENTS |

Received doctrine characterizes real-world phenomena as aggregates of combinable parts, perception as the process whereby people internalize these parts, and cognition as the method by which the parts are constructed into meaningful representations. People are thought, for example, to manipulate bundles of features or dimensions and then match a concatenated aggregate to a prior, mentally constructed generic schema or concept. How such mental constructions work and what criteria are used to select the appropriate combinations of parts remains obscure (see Introduction and chapter 5, this volume). Cognitive theories tend to bypass the actual structural order in the world and, with little explanation, assign the generation of order to mental processes.

In general, problems of order in psychology have been neglected in two related ways: on the one hand by the tendencies of those interested in perception to entertain static models, and on the other by the tendencies of those interested in learning and thinking to entertain models treating temporal order as an instance of mere succession or concatenation of responses. For K. S. Lashley, it was the latter set of issues that was of primary concern. In his classic paper on serial order in behavior, Lashley (1951) suggested that faith in reductive and associationistic accounts of temporal order was misplaced. Lashley observed that such accounts were devised under the assumption of a quiescent system excited by an input, and that if this assumption were false, the whole edifice of associationistic theory might crumble with it. For if the system is always in a (variable) state of excitation, any given pattern of input will always be arriving in an essentially novel context. “Context sensitivity” is the bane of all associationistic models. But, Lashley argued, context sensitivity in this sense is intrinsic not only to the physiological functioning of the nervous system, but also to the structure of virtually all coordinated actions, from leg movements in insects to speech in humans.

Whenever a relatively small number of basic movements—more generally, elements—can be organized or ordered in flexible yet constrained ways, associative models are generally mute on both the flexibility and the constraint. If different temporal permutations of elements can occur, but not every possible permutation, the order(s) must arise from some source other than direct associative connection, which would provide no basis for selecting one ordering over another. Nor are things so different today that we avoid these problems despite the sophistication of modem cognitive theories. Whenever we account for a serially ordered behavior with a computer program, we are still begging all questions of how the temporal organization might arise—the origin of the “program”—or why it should take one form rather than another. This style of explanation accounts for the ordering of actions by the ordering of program steps, a level at which it has again become a “mere succession.” Those who would employ programs as theories are thus just as vulnerable to Lashley’s critique as their associationistic predecessors.

An alternative source for the generation of order lies in the intrinsic coordinative properties of the phenomena to be explained. To give these any serious consideration, as Gunnar Johansson has said, we can no longer seriously entertain static models of perception. Let us consider one of Johansson’s classic demonstrations. If a stationary man with reflectant tape wrapped around his joints is videotaped with bright lights shining on him and presented on a monitor with the contrast turned all the way up and the brightness turned nearly all the way down, an observer sees what looks like a random array of light points on a dark background. Let the man begin to walk, however, and the lights begin to move and the observer sees a constantly transforming yet coherent and compelling pattern that reveals a man walking.

At a stroke, this demonstration shows that information specifying the event “man walking” has none of the features we might think of associating when we think of a man (skin, hair) or walking (legs, ground). It is not enough to say that the moving points exhibit “common fate”—strictly speaking, they do not, for the points do not translate at the same speed in the same direction, far from it. It is rather that the points exhibit precisely the style of “common fatehood” that is unique and specific to a sample of points on a walking man, and not a woman or a rolling wheel. The wheel and the woman too can be conveyed by the information in a point-light display; in fact, two points in motion are apparently sufficient to specify either event for human perceivers. Johansson and his colleagues, in work pioneered in 1950, have given us point-light demonstrations and experiments on a wide variety of rigid and nonrigid motion events.

Johansson’s (1950) demonstrations of human apprehension of generic categories such as “man” or “walking” solely from the intrinsic coordinative properties of a walking man have several implications. The first is that generic classification does not depend on a concatenation of features. The second implication is that event cognition need not depend on the concatenation of static retinal “images.” The third implication, one that is particularly germane to this book, is that there may be no limit to how “cognitive” a judgment can be and still have a firm perceptual basis. When such disparate events as the comprehension of language (Chapter 8, this volume) and the perception of gender (Chapter 13, this volume) may be occasioned by the “same” point-light displays that allow us to perceive rolling and bending events, we must pause and ask: How, using just an abstract syntax of points and lights, could we ever distinguish between the “higher” (cognitive) and “lower” (perceptual) categories of events they make available, or the “higher” and “lower” mental processes to which they putatively correspond?

From an ecological view, order is considered embodied in and intrinsic to the phenomena that we come to know in the world. Chapters 1 through 5 offer theoretical variations on the theme of how the order inherent in the world can be characterized and revealed. In Chapter 1 on universals, McCabe argues that, contrary to widely-held views, universals are not mental entities through which people identify the objects and events of the world. Rather, universals are manifest in the perceivable embodied structure of those objects and events. From this view, organisms perceive informative relationships that specify an object rather than separable components of an object that must be cognitively assembled.

Chapter 2 redefines the concept of schema. Traditionally, schemas are considered mental isomorphs for the plan or organization of an object or event. From this view, one can pass impoverished percepts through this mental mesh and find suitable schematic matches. Shaw and Hazelett offer an alternative conception of schemas as universals perceived interactively in terms of compatibility relationships or affordances that are specific to organism and occasion. The chapter also suggests how perceptions can be schematized over actions to yield internalized knowledge of the environment.

In Chapter 3, Shaw, Wilson, and Wellman introduce the principle of generative specification. According to the principle, a limited but essential set of instances of an event may have the capability to specify or generate a much larger set, possibly even the entire event. The essential generator set of instances exhibits a principle of connection that both links the presented instances and specifies the remainder.

von Foerster opens Chapter 4 with the familiar suggestion that stimuli are apprehended as a function of organism-environment compatibility relations. In his essay, von Foerster also addresses the differences between the ways stimuli and symbols specify their sources, and how the requirements of communication shape symbols in a manner rather similar to the way the laws of nature constrain the forms of stimulus specification.

In Chapter 5 it is the concept that comes under close scrutiny. In their examination of this mainstay of cognitive theory, Balzano and McCabe look at both psychological research and philosophical writings on concepts. Certain traditional views of concepts are found to lead to problems in both of these areas of concern. The authors propose an ecological reformulation of the issues that avoids these difficulties.

REFERENCES

Johansson, G. (1950). Configurations in event perception. Uppsala: Almqvist & Wiksell.

Lashley, K. S. (1951). The problem of serial order in behavior. In L. A. Jeffress (Ed.), Cerebral mechanisms in behavior. New York: Hafner.

1 | The Direct Perception of Universals: A Theory of Knowledge Acquisition* |

University of California, Los Angeles

CONTENTS

Introduction

The Concept of Universals

Universals as Relationships not Components

Cognitive Concepts as Universals

The Uncertain Status of Universals

Universals as Information

Universals as Properties of Real World

Theories of Knowledge

Empirical Realism

Empirical Idealism

Rationalist Idealism

The Kantian Synthesis

Phenomenology

Invariants and Decisions Pertinent to Survival

A Lateralization Hypothesis

Concluding Remarks

When we acquire knowledge, where does it come from and what is its nature? Mutually exclusive theoretical answers to this question are abundant. At one extreme, empirical realists assert that our observations produce raw sense data from which we abstract essential components. Empiricists then propose that we use the process of association to wed these abstracted components so that they sum to a comprehensible object. At the other extreme, rationalist idealists argue that our minds use innately given processes to keep us informed about the world. These “processes” yield knowledge such as Plato’s ideal forms (Cornford, 1935) and Kant’s schemas (1781/1966) that is hypothesized to mirror the structure of real-world things.

Association theory presupposes components as the basic units of knowledge in contrast to schema theory that presupposes systemic structure. Although both the basic unit of knowledge and its source differ for empiricism and rationalism, both views agree that because the person and the world are separate, some form of mental construction (association, innate ideas, schematizing) is crucial for knowledge acquisition. Arguing against the necessity for mental construction, Turvey and Shaw (1979) point out that the belief in an animal/environment dualism gives rise to the notion that when we acquire knowledge, the environment provides the signs (raw material) and the animal provides the significance (meaning). They suggest that it is unclear how animals acquire significance. Further, the possibility for error implicit in the interpretation of “brute matter” by “enlightened mind” makes our survival an admirable feat. There must be a better way to know what is going on.

I propose that we do not use mental mediation to construct perceptual information but apprehend it directly from the schematic structure inherent in the objects of our visual, auditory, and tactile experiences. These schemas are composed of essential invariant relationships that specify the systemic rather than the componential properties of objects and events in light of an observer’s needs and intentions. Contrary to customary explanations, we perceive the schemas of the idealists directly from the external world of the realists rather than the components of the realists in the internal world of idealists.

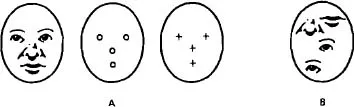

This is not the common view. Ask someone, for example, how they know a face is a face and they will start listing components such as noses, mouths, and eyes. Is our knowledge of faces a function of salient components that we associate to one another in our minds? Or is it a function of the relationships between those components that are available in the face presented to us? A simple demonstration may answer this question. If you maintain the necessary relational invariance of a face and change its features, it will still be recognized as a face (Fig. 1.1A). If, however, you change the relational invariances and maintain the features, the face collapses into a partially random aggregate (Fig. 1.1B).

In effect, we tend to recognize a face in spite of componential changes such as those that accrue with aging (thinning lips, greying hair) or applications of cosmetics (reshaped lips, dyed hair). To maintain knowledge of a face with changing components we cannot simply sum an aggregate of those components, we need to calibrate the relationships between those components that stay constant over changes. Because these systemic relationships are directly available in the visual display as mathematical ratios (Gibson, 1979), it seems unnecessary to conclude that we abstract and mentally reconstruct them. In short, I am proposing that knowledge acquisition involves the direct perception of an informational structure composed of systemic relationships; this informational structure is isomorphic to the actual invariant structure of whatever entity we are apprehending.

FIG. 1.1. Comparison between changing the components and changing the schema of a face.

Knowledge acquisition is then a matter of calibrating structures rather than associating components. A distinction must be made, however, between simply being aware of something and acquiring knowledge of that thing. It is possible to be conscious of seeing the nose, eyes, and mouth (as in Fig. 1.1B) without acquiring knowledge of a facial structure. It is also possible to acquire a facial structure from any one of the examples in Fig. 1.1A without being conscious of doing so. This point is argued later.

Although many cognitive theorists rely on the necessity of mental constructions, their work is pertinent to this point of view; concepts such as schema (Norman, 1979), structure (Piaget, 1971), script (Shank & Abelson, 1977), frame (Minsky, 1975), and prototype (Rosch, 1978) have a family resemblance. They all depict systemic relationships and address the same classic question; are there universals, and if so, what are they and how can we know them?

THE CONCEPT OF UNIVERSALS

A universal is an invariant across particulars (Russell, 1912). It could be a structural invariant that specifies the necessary relationships for a face to be a face and not something else; or it could be a transformational invariant that specifies the lawfully changing relationships within a face due to age (cranial proportions) or expression (anger, sadness, disdain) (see Chapter 3, this volume). Conceptions such as schema, structure, and plan often refer t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- I: INTRODUCTION: EVENT COGNITION AND THE CONDITIONS OF EXISTENCE

- II: ORDER IN BEHAVIOR AND EVENTS

- III: VISUAL EVENTS

- IV: LINGUISTIC EVENTS

- V: MUSICAL EVENTS

- VI: SOCIAL EVENTS

- Author Index

- Subject Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Event Cognition by Viki McCabe,Gerald J. Balzano in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Experimental Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.