![]()

![]()

Chapter 1

Union and segregation

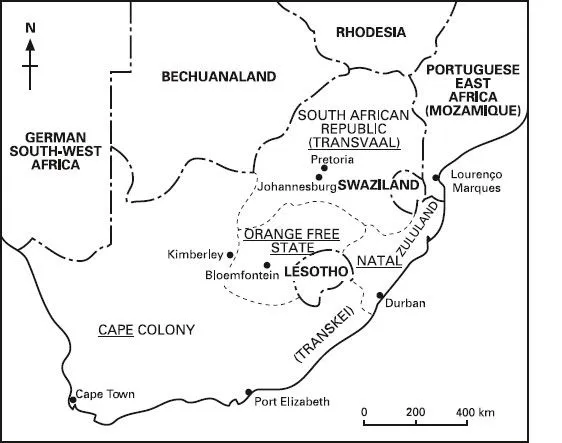

In 1910, a new constitution combined the areas of the Transvaal, the Free State, Natal and the Cape into a union and effectively established the boundaries of a single country (see Figure 1.1). Although central government was instituted under the Union, regional variations continued to exist. The Cape, for example, retained the right to have a non-racial franchise based on property rights, whereas in the other regions black political rights were not upheld. Cape Town became, as it remains, the legislative capital, while Pretoria and Bloemfontein were the administrative and judicial locations, respectively. The Union consolidated the interests of the white population over the black community, a situation that was further demonstrated in the Natives Land Act of 1913. This Act was intended to prevent Africans buying land in areas designated as white, and to stop black tenants living on farms unless they provided an annual minimum of ninety days labour to the landowner.1 The Act also forbade the purchase or lease of land by Africans outside certain areas referred to as reserves and by doing so ‘established the principle of land segregation’.2 These areas, which were adapted in 1936, became the ‘basis of the “homelands” of the apartheid era’.3 By 1910, South Africa was ‘a powerful settler state’, yet only around 20 per cent of the population of the newly formed territory could be classified as white or European.4 The country had attracted European settlers, but the effect could not be compared with the colonisation of North and South America or Australasia.

Figure 1.1 The Union of South Africa, 1910. Province names are underlined

The origins of segregation

A major preoccupation among historians of South Africa has been the need to explain and account for the establishment of segregation. Whose interests did it serve? Why did it become so entrenched? How did it affect the economy? Did it mark the beginning of the ideology that was later to manifest itself in the policy of apartheid? Segregation has been defined as the territorial and residential separation of peoples based on the idea that black and white communities ‘have different wants and requirements in the fields of social, cultural and political policy’.5 The debate about the origins or formative years of segregation go back into the nineteenth century and the policies of the British colonial administration. African reserves were established by the British, while African chieftancy survived in Natal under British rule. When the British were in control, local authority was devolved to African chiefs, who were instrumental in maintaining order. According to Shula Marks, this divide and rule approach was part of British colonial policy and reflected racial perceptions.6 Certainly, notions of racial superiority formed part of the general pattern of colonial rule into the twentieth century. Martin Legassick pinpoints the origins of segregation to the period after the South African War of 1899–1902 between the British and the Afrikaners. The purpose of the war had not been to establish complete British authority throughout the region but to assist the forces of colonialism to gain ascendancy over the Afrikaners.7 Nevertheless, through its victory Britain was able to institute a general colonial strategy and begin to define ‘native policy’.

The conquest of the Transvaal and the Orange Free State in 1900 began six years of British supremacy in South Africa before moves towards Afrikaner political independence eventually culminated in the Act of Union in 1910. These were critical years, argues Legassick, who points to the attitude of Sir Alfred Milner, the High Commissioner of South Africa between 1899 and 1902. He was a leading exponent of the need to ‘reconstruct’ South Africa in order to serve specific interests:

Box 1.1 The peoples of southern Africa

The San (Bushmen) communities occupied most of the southern African region. They were short in stature and lived a hunter-gatherer lifestyle. The San were displaced by the Khoikhoi (Hottentots) communities, who were nomadic pastoralists. The Khoikhoi had developed a pastoral culture by the time of European contact. In the Iron Age and until the fifteenth century AD, Bantu-speaking peoples migrated southwards, developing more complex community structures. In 1652, Jan van Riebeeck established a colony at the Cape of Good Hope to serve as a shipping port for the Dutch East India Company. The colonists were initially known as Boers and latterly as Afrikaners. Interbreeding occurred between the San, Khoikhoi and Afrikaners, which led to the formation of a new ethnic group known as the Cape coloureds. Indians were brought to the country as indentured workers. The racial categories Black African, coloured, Indian and white are still used today as a way of distinguishing different groups.

The ultimate end [of colonial policy] is a self-governing white community supported by well-treated and justly governed black labour from Cape Town to the Zambesi (Sir Alfred Milner, cited in Legassick 1995: 46).

The notion of ‘native’ policy was a paternalistic vision of a subordinated society in which social welfare and social control would be introduced for those people designated as ‘natives’. The South African Native Affairs Commission in 1905 outlined general attitudes towards ‘natives’. As Legassick recorded: ‘The rational policy is to facilitate the development of aboriginals on lines which do not merge too closely into European life, lest it lead to enmity and stem the tide of healthy progress.’ With regard to education, the commission asserted: ‘The character and extent of aboriginal teaching should be such as to afford opportunities for the natives to acquire that amount of elementary knowledge for which in their present state they are fitted.’8 Yet for all the colonial assumptions of native inferiority and primitivism, the mining industry needed black labour. Inevitably, therefore, white and black communities could not be subjected to total separation. A question preoccupied administrators: how could the level of segregation be maximised without affecting the supply of black workers? A form of segregation was advocated in which the white and black races would each develop separately within their own given territories. As far as political arrangements were concerned, both white and black would fashion their own forms of representation. On the eve of 1910, then, a climate of opinion supportive of segregation existed in government circles. Complete segregation of the two races is manifestly impossible, for geography and economics forbids it. But some degree of segregation is desirable, especially in the tenure of land, for the gulf between the outlook and civilisation of the two colours (black and white) is so wide that too intimate an association is bad for both. For many years to come the two races must develop to a large extent on the lines of their own. (Philip Kerr, secretary of the Rhodes Trust, cited in Legassick 1995: 58).

Cheap black labour and industrial development

The discovery of diamonds in 1868 and gold in 1886 led to an economic boom in the late nineteenth century, and a pattern of reliance on migrant black labour began to emerge. Indigenous Africans, dispossessed from the land, became available as cheap labour. Workers were also imported from the Indian subcontinent and became yet another separate ethnic group. The nature of the relationship between racial segregation and the needs of the economy has been explored by a variety of historians. Christopher Saunders outlines the different perspectives, which he identifies as liberal or Marxist in analysis.9 In the 1920s, William Macmillan was the first liberal writer to stress the importance of economics in the development of South Africa. He argued that the demands of industry and the quest for economic growth ran counter to policies designed to keep people apart. In effect, economic growth promoted further integration rather than increased segregation.10 The growth of diamond mining under De Beers Consolidated Mines required the long-term provision of a regular supply of migrant workers. For the first few years of mining, it was not difficult to mobilise Africans to work in the mines, but there were fears that the flow of migrant labour might disappear. While white wage-earners in the diamond industry were employed in jobs requiring skills, black workers were in unskilled jobs. African workers began to be recruited on contracts for periods of several months at a time. During their contract period they lived in the compounds of the mine, thus ensuring that their employers had control over their labour and minimising any risks of strikes or demands for higher wages. White workers could not be treated in this way as their skills were much in demand elsewhere in other countries and they could always threaten to leave.

The early development of the Transvaal gold-mining industry was influenced by the example of diamond mining in Kimberley. A ‘contract’ labour force organised, disciplined and domiciled within the mining compound was accepted as both efficient and effective. According to Denoon and Nyeko, the gold-mining labour force included around 100,000 black workers from the rural areas and 10,000 white workers.11 It was much cheaper for mine managers to employ migrant labourers, who were separated from their families and paid as single workers, than to allow African families to settle around Johannesburg, where employers would have been under pressure to pay higher wages. By 1900, the gold mines were producing over £15 million wor...