![]()

Sustainable intensification in African agriculture

Jules Pretty1*, Camilla Toulmin2 and Stella Williams3

1 University of Essex, Wivenhoe Park, Colchester, Essex, CO4 3SQ, UK

2 International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), 3 Endsleigh Street, London WC1H 0DD

3 Iju Isaga, Agege, Lagos State, Nigeria

Over the past half-century, agricultural production gains have provided a platform for rural and urban economic growth worldwide. In African countries, however, agriculture has been widely assumed to have performed badly. Foresight commissioned analyses of 40 projects and programmes in 20 countries where sustainable intensification has been developed during the 1990s–2000s. The cases included crop improvements, agroforestry and soil conservation, conservation agriculture, integrated pest management, horticulture, livestock and fodder crops, aquaculture and novel policies and partnerships. By early 2010, these projects had documented benefits for 10.39 million farmers and their families and improvements on approximately 12.75 million ha. Food outputs by sustainable intensification have been multiplicative – by which yields per hectare have increased by combining the use of new and improved varieties and new agronomic–agroecological management (crop yields rose on average by 2.13-fold), and additive – by which diversification has resulted in the emergence of a range of new crops, livestock or fish that added to the existing staples or vegetables already being cultivated. The challenge is now to spread effective processes and lessons to many more millions of generally small farmers and pastoralists across the whole continent. These projects had seven common lessons for scaling up and spreading: (i) science and farmer inputs into technologies and practices that combine crops–animals with agroecological and agronomic management; (ii) creation of novel social infrastructure that builds trust among individuals and agencies; (iii) improvement of farmer knowledge and capacity through the use of farmer field schools and modern information and communication technologies; (iv) engagement with the private sector for supply of goods and services; (v) a focus on women’s educational, microfinance and agricultural technology needs; (vi) ensuring the availability of microfinance and rural banking; and (vii) ensuring public sector support for agriculture. This research forms part of the UK Government’s Foresight Global Food and Farming project.

Keywords: Africa; farming; scaling-up; social capital; sustainable intensification

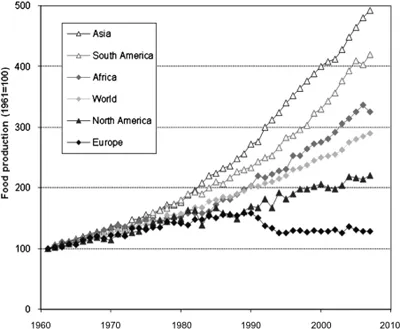

The production challenge for Africa

Over the past half century, agricultural production gains across the world have helped millions of people to escape poverty, removed the threat of starvation and provided a platform for rural and urban economic growth in many countries. Between 1961 and 2007, world agricultural production almost tripled (Figure 1) while population grew from 3 to 6.8 billion. The green revolution drove this production growth with new varieties, inputs, water management and rural infrastructure. Most increases in food production were achieved on the same agricultural land, with net area only growing by 11 per cent over this period (data from FAO, 2009a).

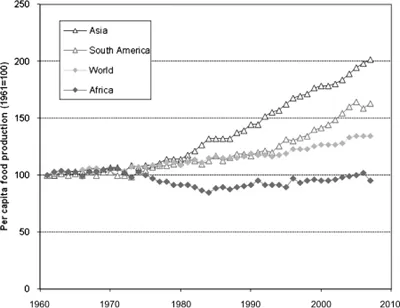

In African countries, agriculture is widely seen to have performed worse than in Asia and Latin America. Production data per capita (of the total population) indicate that the amount of food grown on the continent per person rose slowly in the 1960s, then fell from the mid-1970s and has only just recovered to the 1960 level today (Figure 2). Over the same period, per capita food production increased by 102 per cent in Asia and 63 per cent in Latin America. This has helped to frame a prevailing international view that African agriculture has lagged behind the rest of the world. At the same time, there has been disinvestment in agricultural research, extension and production systems from both governments and international donors (DFID, 2009; Eicher, 2009; Haggblade and Hazell, 2009). Yet agriculture still accounts for 65 per cent of full-time employment in Africa, 25–30 per cent of GDP and over half of total export earnings (IFPRI, 2004; World Bank, 2008). It underpins the livelihoods of over two-thirds of Africa’s poor.

Figure 1 | Changes in net agricultural production (1961– 2007)

However, the net production data (net production is production minus seed required for the next harvest) show something different. These indicate that there has been substantial production growth across all regions of Africa, with output more than trebling (Figure 1) and growing faster than world output (mainly held back by the plateau in agricultural production in Europe). African agriculture has been called stagnant (e.g. Inter Academy Council, 2004), and a failure to achieve sustained productivity growth in smallholder agriculture has led to the temptation to embrace a singular large farm strategy (Collier and Dercon, 2009; Wiggins, 2009). Others, however, provide evidence for a dynamic and adaptive agricultural sector in many parts of Africa, over many years (Haggblade and Hazell, 2009; Röling, 2010).

Figure 2 | Changes in per capita net agricultural production (1961–2007)

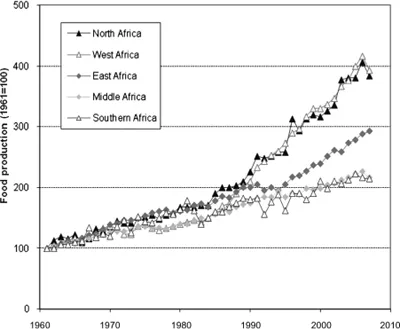

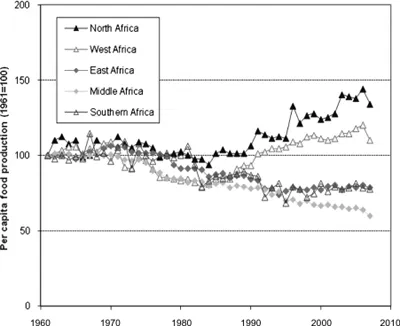

All regions of Africa have seen net agricultural production growth, with the greatest increases in North and West Africa and the least in Middle and Southern regions (Figure 3). However, significant population growth has resulted in per capita production only rising in Middle and West Africa (by 34 and 10 per cent, respectively, since 1960). All other regions have seen dramatic falls in per capita food production: a 21 per cent fall in East Africa, 22 per cent in Southern Africa and 40 per cent in Middle Africa (Figure 4).

Thus, despite the improvements made in African agriculture, continued population growth means that the per capita availability of domestically grown food has not changed at the continent scale for 50 years and has fallen substantially in three regions. As a result, hunger and poverty remain widespread. Of the 1.02 billion people hungry in 2009–10, it is estimated that 265 million are in sub-Saharan Africa and 642 million in Asia and the Pacific (FAO, 2009b). For every 10 per cent increase in yields in Africa, it has been estimated that this leads to a 7 per cent reduction in poverty (more than the 5 per cent in Asia). Growth in manufacturing and service sectors has no such equivalent effect (World Bank, 2008; Wiggins and Slater, 2010). The 2008 World Development Report also noted that public spending on agriculture is lowest in the very countries where the share of agriculture in GDP is highest.

Figure 3 | Africa: changes in net agricultural production (1961–2007)

Figure 4 | Africa: changes in per capita net agricultural production (1961–2007)

It is also clear that conflicts have reduced agricultural production (Allouche, 2010). Food production in 13 war-affected countries of sub-Saharan Africa between 1970 and 1994 was 12 per cent lower in war years compared with peace-adjusted values. Over the period 1970–1997, FAO (2000) has estimated that conflict-related losses of agricultural outputs amounted to $121 billion ($4 billion per year).

Thus the challenge still remains substantial for African agriculture. Countries will have to find novel ways to boost crop and livestock production if they are not to become more reliant on imports and food aid. At the same time, an unprecedented combination of pressures is emerging to threaten the health of existing social and ecological systems (Pretty, 2008; Royal Society, 2009; Godfray et al., 2010). Across the world, continued population growth, rapidly changing consumption patterns, and the impacts of climate change and environmental degradation are driving the limited resources of food, energy, water and materials towards critical thresholds. These pressures are likely to be substantial across Africa (Reij and Smaling, 2008; DFID, 2009; Haggblade and Hazell, 2009; Toulmin, 2009; Wright, 2010).

The sustainable intensification of agriculture

All commentators now agree that food production worldwide will have to increase substantially in the coming years and decades (World Bank, 2008; IAASTD, 2009; Royal Society, 2009; Godfray et al., 2010; Lele et al., 2010). But there remain very different views about how this should best be achieved. Some still say agriculture will have to expand into new lands, but the competition for land from other human activities makes this an increasingly unlikely and costly solution, particularly if protecting biodiversity and the public goods provided by natural ecosystems (e.g. carbon storage in rainforest) is given higher priority (MEA, 2005). Others say that food production growth must come through redoubled efforts to repeat the approaches of the Green Revolution; or that agricultural systems should embrace only biotechnology or become solely organic. What is clear despite these differences is that more will need to be made of existing agricultural land. Agriculture will, in short, have to be intensified. Traditionally agricultural intensification has been defined in three different ways: increasing yields per hectare, increasing cropping intensity (i.e. two or more crops) per unit of land or other inputs (water), and changing land use from low-value crops or commodities to those that receive higher market prices.

It is now understood that agriculture can negatively affect the environment through overuse of natural resources as inputs or through their use as a sink for waste and pollution. Such effects are called negative externalities because they impose costs that are not reflected in market prices (Baumol and Oates, 1988; Dobbs and Pretty, 2004). What has also become clear in recent years is that the apparent success of some modern agricultural systems has masked significant negative externalities now becoming clear, with environmental and health problems documented and recently costed for many countries (Pingali and Roger, 1995; Norse et al., 2001; Tegtmeier and Duffy, 2004; Pretty et al., 2005; Sherwood et al., 2005). These environmental costs shift conclusions about which agricultural systems are the most efficient and suggest that alternative practices and systems that reduce negative externalities should be sought. This is what Giller has called the North–South divide between the ‘effluents of affluence’ and poverty caused by scarcity (Tittonell et al., 2009)

Sustainable agricultural intensification is defined as producing more output from the same area of land while reducing the negative environmental impacts and at the same time increasing contributions to natural capital and the flow of environmental services (Pretty, 2008; Royal Society, 2009; Conway and Waage, 2010; Godfray et al., 2010).

A sustainable production system would thus exhibit most or all of the following attributes:

• utilizing crop varieties and livestock breeds with a high ratio of productivity to use of externally and internally derived inputs;

• avoiding the unnecessary use of external inputs;

• harnessing agro-ecological processes such as nutrient cycling, biological nitrogen fixation, allelopathy, predation and parasitism;

• minimizing the use of technologies or practices that have adverse impacts on the environment and human health;

• making prod...