![]()

[ 9 ]

The Place of Place in Memory

Esther da Costa Meyer

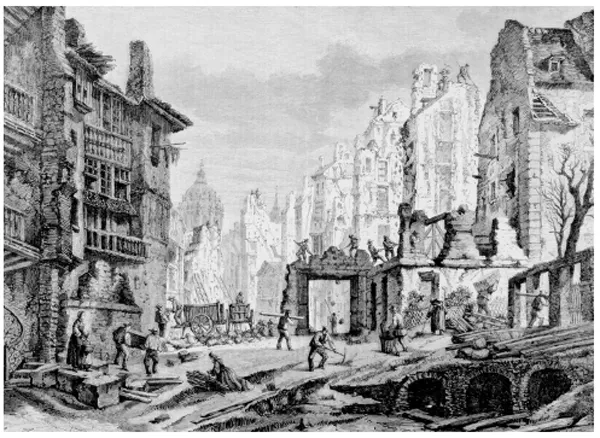

Memory preys on places: there are virtually no un-situated recollections. Yet the mind exacts a price for preserving the past. Recollections are the fruit of conflict and compromise, indelible but unstable. Taking nineteenth-century Paris as my example, a city undergoing violent urban and political change as a result of both industrialization and the revolutions of 1830, 1832, 1848, the coup of 1851, the Franco-Prussian War, and the Commune, I wish to explore the intersection of memory and the built environment that followed these dramatic changes of regime and the attendant iconoclastic consequences. Though Paris witnessed the destruction of huge swaths of urban fabric throughout the century, during the Second Empire (1850–1870) piecemeal interventions gave way to a concerted effort to overhaul the French capital, led by Napoleon III and his prefect, Georges-Eugène Haussmann. By then, the old historic center, the Île de la Cité, and adjacent parts of the Right Bank, had become a vast slum, with tottering tenement buildings and dark, narrow streets [9–1].The area had been devastated by the cholera pandemic of 1832 which coincided with yet another popular revolution, and the government and the leisured classes came to associate the impoverished quarters with both disease and insurgency. Prompted by political as well as hygienic concerns, the government razed the winding alleyways and rotting houses which barely allowed sunlight to trickle down to street level. Though Haussmann also tore down mansions and palaces belonging to the aristocracy, the bulk of the destruction was aimed at the derelict housing stock that served as home to the poor and to segments of the middle class, either in the center or in strategic districts required for the broad new boulevards that would henceforth criss-cross the city.

[9–1]

CHARLES MARVILLE, RUE DU HAUT-MOULIN (SEEN FROM THE RUE GLATIGNY), PARIS, 1865–1866.

[BIBLIOTHÈQUE ADMINISTRATIVE DE LA VILLE DE PARIS / ROGER-VIOLLET]

Parisians complained bitterly of having lost their bearings in what they perceived as a dystopic metropolis. “Blessed are the provincials, the real provincials! They do not move house. Their home belongs to them … It overflows with traditions and memories,” lamented a contemporary:

But we martyrs of the Parisian civilization, camping like nomads under our tent, like Bedouins in the desert, we scatter our lives throughout this vast Sahara of stone, in twenty banal dwellings none of which will preserve our traces. The tracks of our feet efface themselves behind us as if they were written on sand.1

It is hardly surprising that the destruction of cherished homes and familiar streets and squares was experienced as a traumatic ordeal: architecture plays a crucial role in self-definition, giving—or denying—stable points of reference, havens which citizens can call their own and where they feel protected [9–2]. Any site can offer support for associations and subject formation.

[9–2]

DEMOLITIONS ON THE RIGHT BANK DURING THE OPENING OF RUE DES ÉCOLES, PARIS.

[L’ILLUSTRATION, 26 JUNE 1878; BIBLIOTHÈQUE NATIONALE DE FRANCE]

Baudelaire’s friend, the writer Alfred Delvau, echoed this feeling of dispossession but he focused on the destruction of historical landmarks at the height of Haussmann’s campaign of urban renewal:

This evisceration of what was once Romanesque, then Gothic, then Renaissance Paris, then the Paris of Louis XIV —this evisceration is something profoundly melancholic for the artist and for the dreamer who find themselves disoriented as they contemplate the past and interpret the dramas of our history …for those who can see and hear, [stones] can speak—and do so with eloquence [9–3].2

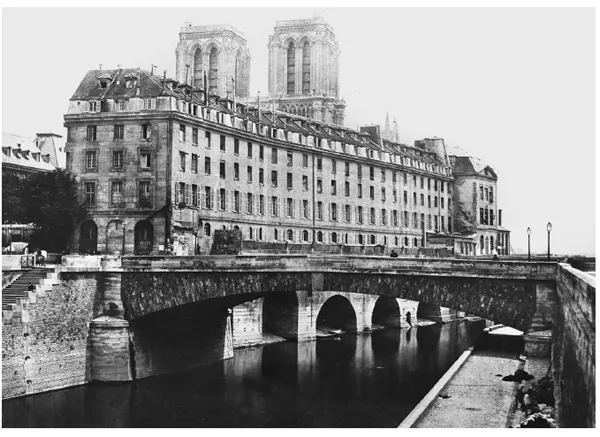

[9–3]

ALBERT HARLINGUE, THE OLD HÔTEL-DIEU, DEMOLISHED IN 1878, WITH THE TOWERS OF NOTRE-DAME CATHEDRAL, PARIS.

[ROGER-VIOLLET]

For Delvau the burden of memory is displaced to architecture which relays highly selected views of the past to successive generations, telling them who they are and where they are coming from. Monuments of historic or aesthetic importance do not always trigger the same deeply felt emotional response as modest homes and neighborhoods. Yet they too help shape identity, collectively in this case, rather than personally. They amplify the individual. “Architecture is to be regarded by us with the most serious thought,” wrote Ruskin. “We may live without her, and worship without her, but we cannot remember without her. How cold is all history, how lifeless all imagery, compared to that which the living nation writes, and the uncorrupted marble bears!”3

Conversely, the idea that the new architecture erected by the regime had no memories was widespread. The strident new buildings of the Second Empire were often felt to be amnesic, untenanted by souvenirs. In the words of the writer Jules Claretie:

Between the quai d’Orsay, on the left, and the quai de Billy, on the right, the Seine flows between superb buildings, but [buildings] without memories, arrogant and new, buildings that do not evoke a single image nor speak of a specific past.4

It is memory, whether that of a single person or a social group, that invests a particular location with singularity and significance, and thus separates place from the undifferentiated sameness of space.5

Haussmann’s aggressive form of redevelopment did not target architecture and urbanism alone, but landscape and topography as well. To make room for new streets and squares, many gardens were razed, along with several hills that obstructed traffic. Entire parts of the center, including all its bridges, were leveled or lowered to facilitate circulation. In 1867, as the capital was being embellished to host the World’s Fair, the authorities shaved 15 meters from the top of the colline de Chaillot, where the Musée d’Art Moderne now stands, to make the hill’s profile less ungainly. Part of the resentment that greeted Haussmann’s slash-and-burn approach to urbanism had to do with the fact that he also demolished sites— not just buildings—of historic importance, such as the Butte des Moulins between the Louvre and the Opera, the mound from where Joan of Arc had launched an unsuccessful assault against the British invaders in 1429 [9–4].6

[9–4]

CHARLES MARVILLE, DEMOLITION OF THE BUTTE DES MOULINS DURING THE OPENING OF THE AVENUE DE L’OPÉRA, PARIS, c. 1877.

[MUSÉE CARNAVALET, PARIS/ROGER-VIOLLET]

Yet despite all vicissitudes, cities stubbornly resist total erasure. According to anthropologist Marc Augé, place is never completely effaced.7 Buildings, streets, and even hills may vanish at a ruler’s whim, but places have a resilience all of their own since meaning does not coincide with their physical limits but encompasses the trains of association which they evoke. The Bastille, a hated symbol of feudalism destroyed by the populace in 1789, continues to this day to serve as a rallying point for the Left. Another famous example of class-bound remembrance with regard to place was the old rue Transnonain in the center of the Right Bank where several workers had been massacred by the police in 1834, an event immediately memorialized by Honoré Daumier [9–5]. For two decades, the site endured as a powerful memento of class warfare until Haussmann finally destroyed the entire street. As he noted candidly in his memoirs: “It was the disembowelment of Old Paris, of the district of uprisings and barricades, by means of a wide central thoroughfare that pierced this almost intractable labyrinth.”8 Nevertheless, Daumier’s lithograph kept the tragedy alive, and rue Transnonain joined the city’s many “repressed topographies” which continue to resonate long after they are gone, sustained by publications, reproductions, and anniversaries.9 In the heyday of the Second Empire, when thousands of inhabitants were displaced and their homes destroyed, Paris became a phantasmatic city, peopled by ghostly buildings and streets that were still part of the citizens’ emotional and intellectual make-up. The affect generated by traumatic political events reinforced collective memory and enabled destroyed buildings and places to endure in human consciousness.

[9–5]

HONORÉ DAUMIER, THE MASSACRE AT RUE TRANSNONAIN, 1834.

LITHOGRAPH.

[ROGER-VIOLLET]

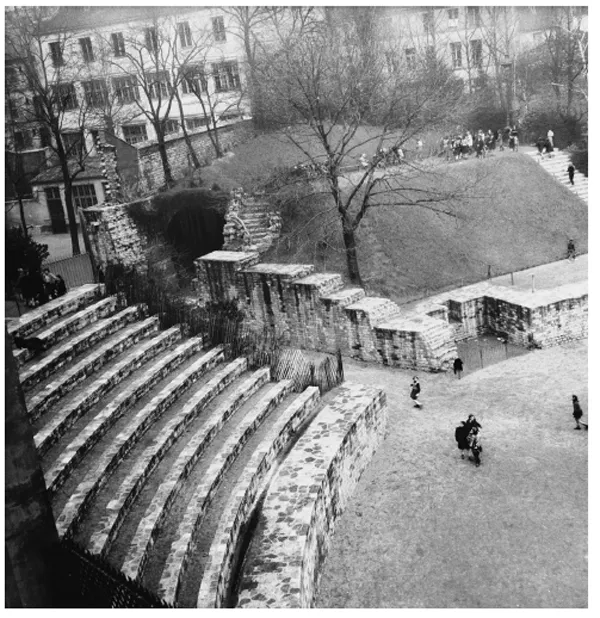

Places have many other ways of survival. The “persistence of the plan,” underscored years ago by Marcel Poëte, and later by Aldo Rossi, reveals how modern cities are still determined by the “direction and meaning of their oldest artifacts.”10 In Paris the old Roman decumanus survives under a modern boulevard.11 “Ancient Paris can be seen distinctly beneath the current Paris,” wrote Victor Hugo in 1867, “like the old text between the lines of the new.”12 The unexpected intrusion of the past in the urban fabric was a common occurrence in Haussmann’s day when the soil was constantly being dug up by his engineers [9–6].13 Despite Baudelaire’s memorable equation of modernity with the “ephemeral, the fugitive, and the contingent,” the new Paris was in fact inseparable from the obstinate undertow of what came before. This metonymic relation of different pasts and presents afforded by old environments makes a mockery of historians’ periodizations. As Aldo Rossi wrote perceptively:

[9–6]

THE GALLO-ROMAN AMPHITHEATER KNOWN AS THE ARÈNES DE LUTÈCE, PARIS, EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURY(?).

[ROGER-VIOLLET]

One must remember that the difference between past and future, from the point of view of the theory of knowledge, in large measure reflects the fact that the past is partly being experienced now, and this may be the meaning to give permanences: they are a past we are still experiencing.14

More modest records of urban history can be found in the gaps and openings of the urban plan. Some record ancient cattle trails, tow paths, or shortcuts taken by tradesmen— water vendors or washerwomen seeking the river—the unheroic but meaningful annals of micro-history. Many still survive in the slant of a street or the widening of an artery where a stream once flowed and no construction was possible. In built environments, as Françoise Choay points out, there are no voids as such: “All non-built areas are nonetheless signifying elements.”15

Toponyms constitute another great reservoir of urban memory. Cities, like Adam, are in the business of giving out names, beginning of course with their own. They endow sites, streets, and squares with specific meanings which have either accrued collectively over the years, or are attributed by fiat. In Paris, street names still recall the trades that once flourished in certain areas of the city like the ru...