![]()

1

Introduction

Geography holds centerstage in the drama of Canadian politics

Wheball 1983

Despite the validity of the quotation, the focus of this book is not on geography but on government and politics. It attempts to document the responses of the multiplicity of governmental agencies to the problems of population growth, urban development, exploitation of natural resources, regional disparities, and a host of other issues which fall within the scope of “urban and regional planning.” Of course, the term has no precise meaning, and its boundaries are unclear. On one interpretation, it encompasses national economic policies (Lithwick 1970), while on another it is basically an extension of municipal law (Makuch 1983). Either approach is legitimate. In the present volume, a generous conception of planning is employed, and an attempt has been made to provide a reasonably comprehensive coverage. However, no claim to completeness is suggested.

The starting point, as befits a book on Canada, is the three levels of government: federal, provincial and municipal. Chapter 2 attempts to summarize the role played by each, but the reader should be warned that the situation is one of constant flux. For anyone wishing to keep up with this shifting scene, there is an endless stream of commentaries.

The federal role is an intriguing one which vacillates between centralization and devolution (Romanow, Ryan and Stanfield 1984), but there are some important land planning functions which it shares with the provinces, and it has a particularly important role in the Yukon and the Northwest Territories. Although “the north” has only 0.3 percent of the Canadian population, it covers almost two-fifths of the land area. Virtually all this land is in federal ownership and is managed by the federal government.

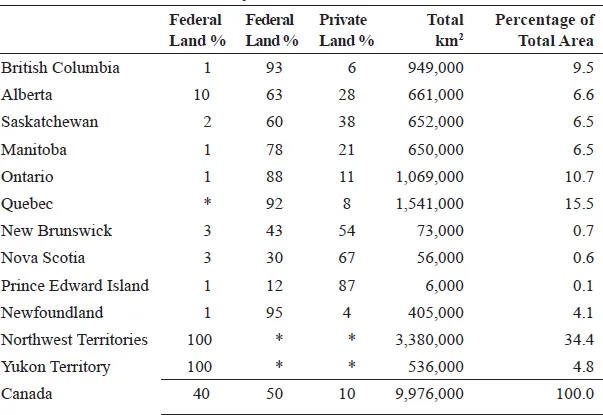

Provincial land ownership varies from 95 percent in Newfoundland to 12 percent in Prince Edward Island (Table 1.1). Much of the provincially owned land is wildland, though rapid and fundamental change is being brought about in many areas by resource development. Environmental issues have become of increasing concern to governments, as have the rights and welfare of native peoples. All provinces have a department responsible for the environment and for resource development (though terminology varies somewhat).

Table 1.1. Provincial Land Areas by Tenure 1978.

Source: Based on Canada Year Book 1980-81, Table 1.8, p. 27

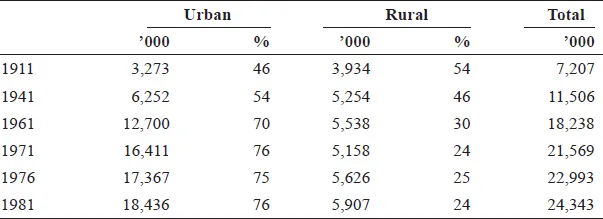

Environmental problems are not, of course, restricted to remote or largely uninhabited areas. Indeed, political and popular interest in “the north” is limited: most Canadians are unconcerned, and there are few votes involved. The center of activity lies in the southernmost parts of the country. Some three-quarters of the twenty-five million inhabitants of Canada live within 500 kilometers of the American border. Three-quarters of the population live in urban areas, and over a half live in the twenty-four census metropolitan areas (CMAs). The latter make up only half of one percent of the land. Indeed, a mere one percent of Canadian land use is urban. Thus there is the paradox that it is only a fraction of the land of Canada which is the concern of urban planning. But this relatively minute area presents major problems, and these have increased with the accelerated urban growth which has taken place since the end of the second world war. In 1941, the proportion of the population classified as urban was 54 percent. (The census definition of urban is an area having a population concentration of 1,000 or more, and a population density of at least 400 per square kilometer.) By 1971 this had increased to 76 percent. Even more striking was the absolute increase: from 6.2 million in 1941 to 16.4 million in 1971. In the following decade, the proportion remained roughly the same, but the number rose to 18.4 million. Much of this growth was natural increase, but a significant amount was the result of large scale immigration (which interacted with economic growth to stimulate further immigration and urban growth).

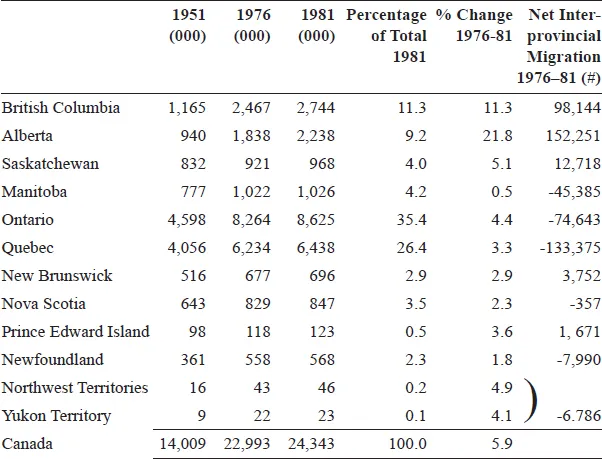

Table 1.2. Canada and Provinces: Population 1951–81.

Source: Census of Canada, 1981

For Canada as a whole, natural increase between 1941 and 1971 totalled 7.7 million, while net immigration was nearly two million (gross immigration was 3.5 million). The fastest period of growth (in absolute terms) was the 1951-61 decade when natural increase of 3.1 million and net immigration of 1.1 million gave a total population increase of 4.2 million.

The growth of the urban population is now proceeding at a rate very close to that for total population growth (5.8 and 5.9 respectively during 1976-81). There are, however, enormous differences among the twenty-four census metropolitan areas. Over this quinquennium, Calgary grew by a remarkable 25.2 percent while, at the other extreme, Sudbury declined by 4.5 percent (Hooper, Simmons and Bourne 1983). Similar differentials to those between the CMAs are to be seen at the provincial level (Table 1.2). Between 1976 and 1981, net inter-provincial migration from Quebec was 133,375, and from Ontario 74,643. The overall direction of the migratory move was clearly westward, with gains of 98,144 in British Columbia and 152,251 in Alberta. Total population increase varied, in percentage terms, from 0.5 in Manitoba to 21.8 in Alberta. It follows that the pressures being experienced by regional and urban planning authorities vary widely.

Table 1.3. Canada’s Urban and Rural Population 1911–81.

Source: Census of Canada, 1981

At a finer level of analysis, there are indications that urban growth in the traditional sense of the outward spread of cities may be giving way to an emerging new pattern of dispersed living and employment locations. This has been documented in the U.S. where, by the early 1970s, migration to metropolitan areas had been reversed. Between 1970 and 1978 the U.S. metropolitan areas had a net loss of 2.7 million. One-sixth of all metropolitan areas lost population. By contrast, three-quarters of all nonmetropolitan counties gained population (Kasarda 1980: 380). This “nonmetropolitan revival” can be seen as a continuation of the processes of dispersal which have operated since the end of the first world war, though some have argued that it represents “a clean break” with the past (Vining and Strauss 1977). The arguments have been reviewed interestingly (though not exhaustively) by Blumenfeld (1982a: 15) who suggests that much “is really a quarrel about semantics.”

Similar forces appear to be operating in Canada, though data limitations have so far precluded the type of locational analysis (of both jobs and homes) that is possible for the U.S. There is, however, an underlying problem of defining the metropolitan orbit. Indeed, it may be questioned whether such a concept is still always relevant. As Blumenfeld has suggested, ultimately the division of settlements into urban and rural is being replaced by an urban-rural continuum, with consequent implications for policy and planning (Blumenfeld 1982b: ii).

Planning for population increase has been a major (but not the only) concern of planning authorities. Chapter 3 deals with the nature of urban plans, while chapter 4 discusses the implementation of plans. In both chapters the objective is to illustrate the great variety of approaches to planning across Canada.

Urban growth in the sixties and seventies gave rise to some acute land problems. The discussion of these is divided between two chapters. Chapter 5 discusses a range of matters such as the escalation of land prices, land speculation and similar problems (together with broader issues including expropriation and nonresident ownership of land). This chapter is thus focused on a range of particular problems. Chapter 6, by contrast, deals with a number of important land uses, such as agriculture, aggregates and forestry.

Of these, agriculture has been perhaps the most pervasive and difficult problem, particularly since many of the urban areas are located near (and in) rich agricultural land. This is a consequence of Canada’s settlement history:

Initially, settlement was oriented towards areas of fertile soils which could supply agricultural products. The success of initial settlement often related to the area’s agricultural productivity, which then formed a solid basis for subsequent growth. The result has been a conflict between urban areas and agricultural resource lands; both urban and agricultural uses are competing for the same land resource (Neimanis 1979: 3).

Agriculture has been (and remains) important not only in urban planning but also in regional planning. As is shown in chapter 7, the need for agricultural rehabilitation and development provided the starting point for regional planning at the federal level.

Chapter 8 is devoted entirely to one province: Ontario. It is, in fact, a detailed case study. This is justified by the fact that Ontario has attempted more in the field of regional planning policy than any other province. It has also had at least its fair share of failures. A fuller account of regional planning in Ontario is given in a special issue of Plan Canada (1984).

That regional planning differs significantly between the provinces is abundantly clear from chapter 9 where the discussion relates to the new regional planning system in Alberta, Quebec’s long struggle to introduce regional planning, and British Columbia’s attempts to coordinate regional resource management with planning.

It would have been interesting to compare metropolitan planning in these four provinces, taking for example Toronto, Vancouver, Calgary and Edmonton, Montreal and Quebec. This, however, clearly warrants a book on its own, and the only metropolitan area discussed is Toronto.

Currently we are witnessing an unprecedented Stress on Land (Simpson-Lewis et al 1983). Urban growth, pollution, waste disposal, mining, soil degradation, airport facilities, the disturbance of forest ecosystems …; a full list would be surprisingly lengthy. As governments have become aware of these environmental problems, and as they have become increasingly politicized, the realm of environmental protection has expanded. This is the subject of chapter 10, in which several are selected for discussion. Initially, the emphasis is on the respective roles of the federal and provincial governments. This is appropriate since the major problems in environmental protection are political and administrative (as well as scientific).

As in other matters, there are marked differences in approach and effectiveness between the provinces, but the main focus is on the federal government and Ontario (partly because of their relative wealth of publications). The importance of the governmental apparatus, however, should not be overemphasized. As is noted in chapter 2, it is not always easy to draw a line between scientific and political judgments. Environmental impact assessments constitute an attempt to do precisely this: to objectively appraise the impacts which a proposed development might have on the environment (now extended to encompass social and cultural as well as physical dimensions). At the same time, however, they increasingly attempt to obtain the maximum amount of public input. How far the public’s attitude towards a development can be weighed against “scientific facts” is an open question, and one which experience is showing to be difficult to resolve. The matter is made more complex because typically there is more than one “public”: or to use political terminology there are often several constituencies. Resolution of planning problems cannot be “scientific”: attempts may be (and are) made to make the process as complete and fair as possible, but inevitably the outcome is based upon a mixture of scientific, social, economic and political issues as perceived by the multiplicity of organizations and individuals involved in the planning process.

This leads us into the subject matter of the last main chapter, which is titled simply “Planning and People.” Emphasis here is laid on the essentially political nature of the planning process. A major argument put forward in this chapter is that of a natural bureaucratic response to regard objectors to planning proposals as “people in the way.” The phrase is the title of an extraordinary study by J.W. Wilson of the Columbia River Project (Wilson 1973). The extraordinary feature is that Wilson was a turncoat: from being an operational planner he became an independent researcher of operational planners.

In fact, values and subjective judgments are endemic in planning debates. Moreover, to make the issue even more difficult, not only do “the communicating parties use different vocabularies or languages to talk about the same thing, but rather in fact they use differing structures of reasoning. If, as is common, the parties remain unaware that they are using different structures of reasoning, but are aware only of their difficulties, each party tends to perceive the communication difficulties as resulting from the other parties’ illogicality, lack of intelligence, or even deceptiveness and insincerity” (Maruyama 1974: 81).

Finally, there is a short epilogue which attempts some reflections on the nature of Canadian planning. In writing this it became very clear that the issues raised would repay much fuller study on the lines indicated at the beginning of the Preface. Preliminary work on this is in progress.

![]()

2

The Agencies of Planning

The Federal Role

Canada is the only country in the world where you can buy a book on federal-provincial relations at an airport

Anon

Planning, in the narrowest sense of the term, is clearly a local matter, and thus it is the responsibility of local and provincial ...