![]()

1

The International Response to Avian Influenza: Science, Policy and Politics

Ian Scoones

Introduction

On 11 June 2008 another outbreak of highly pathogenic avian influenza (H5N1) was reported in Hong Kong – the site of the first reported human deaths from this virus in 1997. Media reports portrayed the possibility of a major catastrophe. Anxious citizens stopped eating chicken. With China hosting the Olympics in a matter of weeks, concerns were raised in the highest circles about the consequences of an outbreak, for world profile and for business. Politicians wanted firm action. On 20 June, officials proposed a package of US$128 million for market restructuring which would put the small-scale poultry sector and wet markets out of business. Traders rejected the proposal and many consumers argued that the alternative frozen supermarket chickens were not what they wanted. Others argued that attempts at regulating imports and banning wet markets would be futile. Informal, unregulated trade abounds, and with South China being a known, if poorly reported, hot spot of avian influenza virus circulation, the chances of keeping Hong Kong free of the disease were very small indeed. Yet, sceptics argued that the proposed measures were more about political grandstanding and public relations than sensible, science-based control policies. The net consequences for the livelihoods of farmers, traders and poorer consumers would be negative, they argued, with only the well-connected large suppliers and supermarkets benefiting. But, given the fears around viral mutation into a form capable of efficient human-to-human transmission, others concluded that precaution, even if drastic, would be the most appropriate route.1

Less than a year later, swine flu hit the media headlines. Again an influenza virus – this time H1N1 – was threatening human health and there was the potential for a major human pandemic. On 30 April 2009, Britons woke up to the headlines ‘Swine flu: the whole of humanity is under threat’.2 Reporting the warnings of Margaret Chan, the Director General of the Geneva-based World Health Organization (WHO), the media had a field day. Outbreaks in Mexico, and an apparently high mortality rate, were causing grave concern. The suspected origins were pigs, although an intriguing debate ensued about the naming of the virus with the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) and the Chief Veterinarian of the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) arguing that swine flu was the wrong name because the virus affecting humans and had not been isolated in pigs.3 Subsequent genomics work showed incontrovertibly the association and that the virus was a combination of North American and Eurasian pig viruses, combined with avian and human viral strains (Garten et al, 2009). Others pointed out that inadequate surveillance of animals and poor coordination between human and animal public health authorities was probably a large part of the reason for the lack of understanding about the emergence of the virus, and the slow response to the potential threat in Mexico (see Anon, 2009; Butler, 2009; Neumann et al, 2009) The politics of naming and blaming dominated the debate. In Egypt for example the authorities attempted to cull all pigs in the country, even though there had been no outbreak detected. Here politics and religion dominated science and public health concerns and the global panic about swine flu was used to justify discriminatory intervention against pig-keeping Christian groups. Through air travel in particular, this potentially deadly viral cocktail began to spread across the world and in the coming weeks the WHO raised the alert levels, with an official ‘phase 6’ pandemic announced on 11 June 2009.4

Pandemic preparedness plans designed in response to the avian influenza threat had been dusted offand implemented. A huge mobilization of resources took place. Fortunately, human mortality levels outside Mexico were low and the pandemic was mild with a low impact (Fraser et al, 2009). Although many pointed to the scare tactics employed by the media and complaints were made about a disproportionate response, others observed that the risks were and are real and the potential for further genetic reassortment of the virus, mixing with strains of the bird flu virus, H5N1, remains a real concern.5 This may not have been the long-expected ‘big one’, but it had been, many commentators argued, an important precursor of something far more serious.

These examples highlight the complex trade-offs involved in policy processes around diseases that affect humans and that emerge from animals (zoonoses). These trade-offs are intensely political, pitting different interests and groups of actors against each other. Public image, business interests and poor people’s livelihoods are all involved in a complex mix. And the science is often so uncertain that firm decisions based on exact predictions and precise measures are impossible. Judgements – normally political judgements – are made, and these are necessarily highly contextual. Media pressure, political effectiveness, implementation capacity and geopolitical positioning all come into the picture.

Thus, in order to understand the politics of the international policy response to avian influenza – and indeed any other similar disease – we must explore an intersecting story of virus genetics, ecology and epidemiology with economic, political and policy machinations in a variety of places: from Hong Kong to Washington, to Jakarta, Cairo, Rome and London. This book offers one, necessarily partial and incomplete, view of the story of the avian influenza response over the last decade – and particularly the last few years when over $2 billion of public funds have been mobilized. It focuses on the interaction of the international and national responses – in particular on Cambodia, Vietnam, Indonesia and Thailand – and asks how resilient is the disease surveillance and response system that has been built for avian influenza or indeed other emerging diseases?

Why is this story important? In particular it is because the avian influenza story is seen by many as a ‘dress rehearsal’ for a major pandemic emerging from a zoonotic disease, whereby a combination of viral genetic change and ecological circumstance results in the transmission of a new disease among humans, with devastating consequences. The A(H1N1) swine flu outbreaks in 2009 rang major alarm bells. Was this going to be a major pandemic with massive human mortalities? Pandemic response systems swung into action, emergency committees were established, contingency plans unfolded, stockpiles of drugs were created and, as discussed above, the media went into a frenzy. But such fears are not without foundation. The 1918 human influenza pandemic killed at least 50–100 million people globally.6 Estimates for future pandemics vary widely, but a simple calculation sees three times that number given the world’s increased population.7 And we are of course in the midst of the catastrophic pandemic of HIV/AIDS which had its origins as a zoonosis and which, for a range of reasons, was not spotted early enough and spread widely. Between 1940 and 2004 over 300 new infectious diseases emerged, some 60 per cent of which were zoonoses from animals.8 That a pandemic influenza strain has not yet emerged from the H5N1 virus currently circulating, or from some combination of H5N1 and A(H1N1) – at least at the time of writing this book – is no reason for complacency. A serious influenza pandemic will happen, it is argued convincingly, some time, somewhere, and we had better be ready for it. For this reason, exploring the successes and failures of the avian influenza response to date is a crucially important task.

The avian influenza response story is especially fascinating because it offers insights into some wider dilemmas surrounding animal health, production and trade, public health, emergency responses and long-term development, and their intersection with the global governance of health. As with many high-profile policy debates, there are multiple, competing policy formulae and diverse, sometimes conflicting, intervention responses. There is a vast range of actors, associated with numerous networks, often cutting across sectoral boundaries, public/private divides and local, national and global settings. Avian influenza has caused a massive mobilization of public funds, involving numerous agencies and resulting in countless initiatives, programmes and projects. Yet there has also been often remarkable collaboration across what had previously been deep organizational and professional divides. There has also been a range of organizational innovation and experimentation. These offer important insights into what to do – and indeed what not to do – in the future. In particular, this book explores the potentials of what has been dubbed a ‘One World, One Health’ approach,9 where human, animal and ecosystem health are integrated, through combined surveillance and response strategies.

The avian influenza response thus offers some important perspectives on some of the big issues of the moment. These include, for example, how to respond to uncertain threats which have transnational implications; how to cut across the emergency– development divide, making sure crises result in longer-term responses as well as dealing with immediate needs; how to balance interests and priorities between assuring health and safety as well as sustainable livelihoods; how to operate effectively in a complex multilateral system, within and beyond the UN; what a commitment to ‘security’ in health and livelihoods really means in practice and much, much more.

These are of course all massive, and highly contentious, issues, and this book will not provide any neat and tidy answers. What it aims to do instead, through an analytical lens which looks at the politics of policy processes, is to shed light on these issues, sharpening the questions raised and the trade-offs implied. For, as the title of this chapter suggests, it is at the intersections of science and politics where key insights into policy are uncovered and it is in this, often disguised, arena where some of the most important indicators as to future actions and options are found. As the global avian influenza response moves towards a bigger, overarching One World, One Health agenda proposed at the December 2007 Delhi inter-ministerial meeting and elaborated at the 2008 Sharm El-Sheikh international ministerial conference and the 2009 consultation in Winnipeg, these issues become even more pertinent. This book therefore asks: given the lessons of the international avian influenza response to date, what should be the features of an effective, equitable, accountable and resilient response infrastructure at international, national and local levels – both for avian influenza and other emerging infectious diseases? In essence, what should a One World, One Health initiative look like in practice?

The International Response

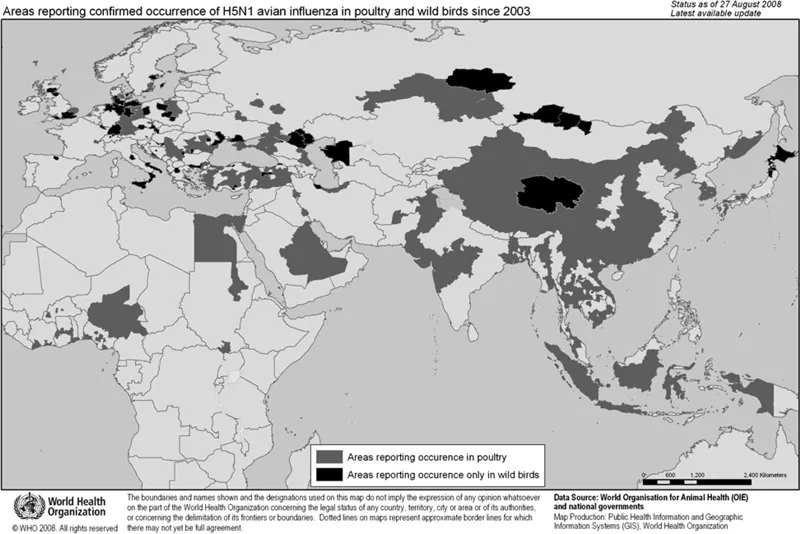

There has now been more than a decade of experience since the Hong Kong avian influenza H5N1 outbreak of 1997 when 18 people were infected and 6 died. Since 2003, 283 people are reported to have died from infection with this virus across the world, with mortalities highly concentrated in a few countries, mostly in southeast Asia.10 The avian virus has spread across most of Asia and Europe with regular, usually seasonally defined, outbreaks in poultry. In some countries – and the list varies, but always includes Indonesia, China and Egypt – the disease has become endemic among bird populations. In response to these outbreaks hundreds of millions of poultry have been culled, affecting the livelihoods and businesses of millions.11 Thus, while a major human pandemic has thankfully not occurred as a result of the spread of H5N1, the disease and the consequences of the resulting policy interventions have been far reaching and, in certain contexts for certain people, dramatic. Figure 1.1 offers a map of the spread of the virus across the world.

Figure 1.1 Confirmed occurrence of H5N1 in poultry and wild birds since 2003

The H5N1 avian influenza virus – introduced in more detail below – has thus had a substantial impact. How then has a miniscule virus, made up of a few strands of RNA and a protein coating which might, or might not, have a devastating impact on human populations, influenced policy and practice globally? The Appendix on page 245 shows two timelines stretching over the period since 1997, with a number of key moments identified.

As the timelines show, biological, economic and policy processes are mutually intertwined, co-constructing the response. Epidemiological processes of spread – through wild birds, trade or poor market hygiene – are influenced by policies which result in mass culls of poultry, banning wet markets or imposing import regulations. In different settings these measures may restrict spread – or actually increase it, as they drive activities underground. What has happened in practice is highly dependent on the way different contexts affect this interplay between biology, economic interests and policy. In some parts of the world (notably in Europe, but also in Thailand, Hong Kong and, for a time, Vietnam) policies have influenced disease incidence and spread in ways that have seen intermittent outbreaks being controlled and managed increasingly effectively. In other places, this has not been the case and the disease has become endemic, with regular outbreaks occurring and little likelihood of eliminating the virus.12 In terms of the global policy response, it is the former context – of controlled virus and stamping-out of intermittent outbreaks – that has dominated thinking and practice, while the latter context – of an endemic disease situation – has been largely ignored, or denied.

Concerns in many quarters rose as the disease spread from isolated outbreaks in southeast Asia, first to central Asia, then to Europe and Africa. The speech by US President George Bush in September 2005 to the United Nations indicated strongly that the US was taking this very seriously.13 In the post 9/11 world where threats to US homeland security could arise from terrorism and infectious disease – and potentially deadly combinations of the two – the spectre of a major pandemic rang alarm bells. As a US government official put it:

In the wake of 9/11 scenario and the transformation of the institutional response capability within the US, we were looking at a sort of all hazards approach, and how the White House sees that with homeland security, it was kind of natural to see this potential threat in a broader context and to respond to it in a fairly robust manner … Also the sensitivity to criticism that came out of Katrina lent the whole White House focus a sharp edge. We don’t want to be criticised like that again so we really need to do a good job on this … It is one of our high priorities because this is a presidential initiative and the president has an interest in what is going on … there’s the White House, the Homeland Security Council, that’s a sort of national security council, and they’ve had the primary lead, and it’s a real lead. If something hap...