![]()

1

Multiple Paths to Reducing Prejudice and Discrimination

Stuart Oskamp 1

Claremont Graduate University

Prejudice is one of the most-studied areas in all of social science. However, most of this study has been directed at understanding the nature, causes, and consequences of prejudice. Though reducing prejudice has been the implicit goal of many researchers, relatively little research has been directed specifically at the crucial topic of how to reduce prejudice and discrimination in our societies. That is “where the rubber hits the road”-where psychological theory and research findings must combine to create effective programs for improving social conditions. The vital importance of this topic is emphasized in this quotation:

[Though they may have had] a possible evolutionary advantage, prejudiced intergroup attitudes-with their potential for periodic eruption in overt intergroup conflict-have now become an extremely serious threat to the continued survival of human society and civilization. (Duckitt, 1992, p. 250)

We are all aware of horrendous examples of nations that have erupted in open warfare between rival ethnic or religious groups, such as the former Yugoslavia, Rwanda, and Northern Ireland. On a smaller scale, the United States also still suffers every year from hundreds of vicious hate crimes, including killings of African Americans, gays, and other minorities. Despite these appalling cases, we should keep in mind that remarkable positive changes have occurred in our society and others, in the direction of greater harmony and reduced prejudice. Examples of this kind of progress include the marked change in cultural values and norms affecting intergroup relations in the United States since World War II and the more recent transformation to a more equalitarian political system that has replaced apartheid in the Union of South Africa.

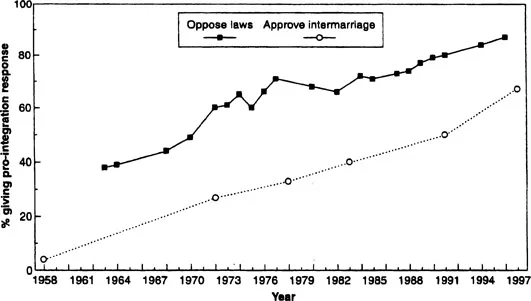

Empirical demonstrations of these favorable intergroup changes can be seen in the dramatic upward trend of responses to all the standard survey questions concerning tolerant racial attitudes and beliefs, as measured in national samples of the U.S. White population since the 1940s (cf. Schuman, Steeh, & Bobo, 1985; Schuman, Steeh, Bobo, & Krysan, 1997). As one example, note the sharp rise over 40 years in approval of even the most controversial interracial topicopposition to laws against racial intermarriage, and approval of intermarriage (see Figure 1).2

To counterbalance this apparently rosy picture, research has also pointed out that attitudes and actions aimed at implementing these tolerant and equalitarian attitudes have not gained nearly the same degree of acceptance in the U.S., and that we clearly have a long way to go to reach a society where all groups experience equal opportunity and full social justice (Schuman et al., 1997). Terms for the new, more subtle forms of prejudice and discrimination include modern racism, aversive racism, and symbolic racism. Recent research on implicit prejudice has demonstrated that consciously expressed attitudes do not capture the full extent of prejudice in modern societies (Banaji & Greenwald, 1994; Dovidio, Kawakami, Johnson, Johnson, & Howard, 1997). However, despite the indications of continuing prejudice and of backsliding or backlash against racial tolerance, the dramatic changes toward fuller social acceptance of all groups in our society are encouraging marks of progress.

FIG. 1.1. Trends since 1958 in national samples of U.S. Whites about attitudes opposing laws against racial intermarriage (NORC) and approving intermarriage (Gallup). Source: Reprinted by permission of the publishers from Schuman, Steeh, Bobo, and Krysan, Racial Attitudes in America: Trends and Interpretations (p. 118), Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Copyright 1997 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College.

Causes of Prejudice and Discrimination

Efforts to reduce prejudice necessarily have to be built on an understanding of the causes of prejudice. Many authors have noted that the causes of prejudice and discrimination are multiple and elaborately intertwined. For instance, Hamilton and Trolier (1986) wrote:

Any particular form of stereotyping or prejudice, such as racism, is in all likelihood multiply determined by cognitive, motivational, and social learning processes …. Therefore, any attempt to understand such phenomena as a product of one process alone is probably misguided. (p. 153)

The same should be said about attempts to reduce prejudice-they need to consider and combat the multiple causes of prejudice. In analyzing the causes of prejudice and discrimination, Duckitt (1992) proposed a four-level model of possible factors. He listed:

- genetic and evolutionary predispositions.

- societal, organizational, and intergroup patterns of contact and norms for intergroup relations-e.g., laws, regulations, and norms of segregation or unequal access, which maintain the power of dominant groups over subordinate ones.

- mechanisms of social influence that operate in group and interpersonal interactions-e.g., influences from the mass media, the educational system, and the structure and functioning of work organizations.

- personal differences in susceptibility to prejudiced attitudes and behaviors, and in acceptance of specific intergroup attitudes.

Duckitt further suggested that efforts to reduce prejudice and discrimination need to work at all of these levels, but that “the higher the level of intervention [i. e., lower numbers], the greater will be its potential impact’ (p. 251).

Prejudice Reduction Interventions. Different approaches are needed in order to counteract these different causes of prejudice. At level 1-genetic and evolutionary predispositions-we may conclude that relatively little can be done on a short-term or intermediate-term basis to change patterns of human interaction that have this kind of built-in biological foundation. However, interventions at the later levels may gradually change humans’ evolutionary inheritance of prejudice in the direction of greater acceptance of outgroups.

Thus level 2-laws and widespread norms-becomes the most powerful arena for changing patterns of human interaction. As psychologists, we tend to operate mostly at levels 3 and 4-group influence and interpersonal interactions-but we should keep strongly in mind the importance of efforts toward interventions at level 2. A classic example of level-2 actions is the 1954 and 1964 decisions of the U.S. Supreme Court that outlawed desegregation in public schools. Other examples are equal-opportunity and affirmative-action laws and regulations, which have had nationwide effects on norms, attitudes, and behavior. In the opposite direction, recent reversals of affirmative-action regulations in some states may have the unfortunate effect of increasing prejudice and discrimination.

Moving to level 3-influence processes-we need to distinguish between two rather different sublevels. Duckitt emphasizes mass influence processes such as the mass media, the education system, and work roles in organizations, and he pays less attention to smaller-scale group and interpersonal influence processes, which are the type that psychologists most often study in research and try to modify in practical applications. His emphasis is heuristic because, again, the broader the level of change efforts, the more impact they are likely to have.

Thus, in the mass media, programs like Cosby or ER, which show different ethnic groups interacting in generally friendly, equalitarian, and nonstereotypic ways, are important influences. Within the educational system, programs such as the widely disseminated series on Teaching Tolerance from the Southern Poverty Law Center are valuable, and another excellent informational resource is the recent pamphlet Racism…. and Psychology published by the American Psychological Association (Feinberg, no date). Within work organizations, it is vital to move toward explicit standards for selecting and promoting individuals that guarantee equal opportunity and that value diversity of backgrounds and experiences relevant to the job at hand. At the other extreme, media programs, educational procedures, and work structures that present nonequalitarian or stereotypic models obstruct efforts toward the reduction of prejudice.

Additional Variables in Interventions. Still at level 3, the distinction between normative and informational social influence (e.g., Deutsch & Gerard, 1955) should be useful in helping to classify and structure influence attempts. The above examples of media portrayals and work-organization standards illustrate normative social influence, whereas informational programs aim to instill cognitive knowledge. Educational programs are mostly informational, though teacher influence processes can certainly also set normative standards. At the small-group and interpersonal sublevel of influence, psychologists’ efforts to reduce prejudice often use both normative and informational pressures.

Another useful distinction is between influence attempts where the recipients are passive, as in listening to a speech or movie, and ones where they are active. Research has found that active participation generally produces stronger and longer-lasting attitude and behavior change than does passive participation (Oskamp, 199 1). The active interventions in prejudice reduction programs very often involve interactions with outgroup members.

Examples of actual programs may help to clarify the above categories. Examples of informational approaches include programs of multicultural education in school settings (e.g., Aboud, in press; Banks, 1997; NCSS Task Force, 1992) and training programs about diversity, usually in industrial settings (e.g., Ellis & Sonnenfield, 1994; Tan, Morris, & Romero, 1996). Both informational and normative approaches may be passive (as in exposure to TV or other normative presentations) or active experiences (as in interacting with outgroup members). Examples of interactive interventions include programs of cooperative learning in the schools (e.g., Johnson, Johnson, & Holubec, 1994) and intergroup dialogue programs, usually in college or community settings (e.g., Gurin, Peng, Lopez, & Nagda, 1999).

Finally, at level 4-personal differences-Duckitt places personality factors that make individuals susceptible to prejudiced or nonprejudiced messages and attitudes. He suggests that these factors usually can only be modified through fairly intensive group or individual psychotherapeutic approaches-the province of clinical and counseling psychologists. (He also places at this level attempts to change individuals’ specific intergroup attitudes, which seem to me to fit better under the level-3 subcategory of group and individual influence attempts.)

We can conclude, from the above analysis of the varied causal factors in prejudice, that psychologists might try to develop interventions to reduce prejudice using the following different approaches:

- laws, regulations, and widespread norms-the most powerful method

- mass influence processes-either normative or informational, either passive or interactive

- group and interpersonal influence processes-either normative or informational, either passive or interactive

- psychotherapeutic approaches to modify personality characteristics

Another Theoretical Approach

A more fine-grain theoretical view about the causes of prejudice that pertains mainly to Duckitt’s levels 3 and 4 (and somewhat to level 2) has been proposed by Stephan and Stephan (Chap. 2 in this volume). They consider intergroup fears and threats as major causes of prejudice, and they list four main bases of prejudice:

- realistic threats from an outgroup

- symbolic threats from an outgroup

- intergroup anxiety in interactions with outgroup members

- negative stereotypes of the outgroup

It should be possible to focus on these factors in efforts to reduce prejudice. Stephan and Stephan indicate that the four bases of prejudice are typically interlinked and operate in conjunction with each other rather than separately, and therefore prejudice reduction efforts need to focus on reducing several or all of them together. They further suggest that cognitive or knowledge-based interventions can reduce feelings of threat (both realistic and symbolic), and that groupinteractive interventions can reduce negative stereotyping and intergroup anxiety.

Programs to Reduce Prejudice and Discrimination

Though most methods of reducing prejudice share some common features, they can be roughly categorized into behavioral, cognitive, and motivational approaches, according to their most prominent elements. Each of these categories of approaches operates primarily at Duckitt’s level 3, although in some instances they may also operate at level 2 (through laws or regulations) or level 4 (through psychotherapeutic interventions).

Behavioral approaches include intergroup contact under specified conditions, cooperative learning techniques, and structured experiences as a target of prejudice. Cognitive approaches include attempts to change stereotypes and attitudes through various mechanisms-e.g., recategorization of group memberships into a common ingroup having superordinate goals, or decategorization of group memberships through crosscutting roles and activities that help outgroup members to be seen as personalized individuals. Motivational approaches include reduction of feelings of threat from an outgroup, demonstrating that the outcomes of ingroups and outgroups are interdependent, and emphasizing that each individual has some personal accountability for intergroup events. Two techniques that combine cognitive inputs with motivational pressures are spotlighting of a person’s values that are relevant to treatment of outgroups, and the related procedure of inducing guilt feelings about one’s individual failure to enact values of equality.

Examples of most of these techniques are given in the following paragraphs, which describe six specific techniques that have been used systematically to reduce prejudice and its expression and which have had some research attention.

1. Reducing Realistic Conflict. Based on Stephan a nd Stephan’s list of the causes of prejudice, a good way to reduce prejudice due to realistic threats from an outgroup is to reduce the bases of realistic conflict. This might be done by sharing power with the outgroup more equally, or ceding the outgroup specific areas of responsibility or authority, or “enlarging the pie” of resources available to the contending groups. These kinds of solutions are often proposed and sometimes accomplished in research on intergroup negotiations (e.g., Fisher & Ury, 1981; Thompson, 1990). Suggested methods have been called “integrative bargaining” or “interactive problem solving.” However, a major obstacle to this approach is that it conflicts with the dominant group’s usual strong motivation to maintain power over subordinate groups (cf. Sidanius & Veniegas, Chap. 3 in this volume).

2. Publicity About Role Models. Fears based on symbolic threats from an outgroup can often be countered by publicity about or exposure to role models who contradict the sym...