![]()

PART III

Phonetics in Social Interaction

![]()

Chapter 7

Diphthongs in Colloquial Tamil

R. E. Asher

University of Edinburgh

E. L. Keane

University of Oxford

‘Wise men now agree, or ought to agree, in this, that there is but one way to the knowledge of nature’s works; the way of observation and experiment.’

—Thomas Reid (1764, p. 3)

This chapter analyses one aspect of the difference between formal and informal Tamil. Since the appearance of Ferguson’s article on diglossia (1959), Tamil has been seen as one of the clearest representations of the phenomenon (see Britto, 1986). As is common in such situations, the formal, or ‘higher,’ variety is not only the language of writing but is also used in such contexts as the reading of news bulletins on the radio or television or the delivering of a lecture or a political speech. It is true that in the middle decades of the 20th century, two senior political figures, C. Rajagopalachari (Rajaji) and E. V. Ramaswami Naicker (E.V.R.) normally spoke from the platform in the informal, or ‘lower,’ variety, but this was very exceptional. For the most part, the nature of the social context determines the choice made by the speaker.

The two varieties are clearly distinct at all levels: phonetic and phonemic, morphological, syntactic, and lexical, and it is possible to tell from even a small fragment of an utterance with which variety one is concerned. That is not to say that features of one variety never intrude into the other (see Asher & Annamalai, 2002, p. 73), but that the intrusive elements will be very limited. Our concern here is principally the phonetic and phonemic, in that we focus on the colloquial equivalent of what in the formal style is a diphthong.

Analyses of the phonology of the formal variety of Tamil have tended to be strongly influenced by the Tamil writing system (see Annamalai & Steever, 1998, p. 101). The justification for this is that, as far as native Tamil elements are concerned, the script is both economical and systematic and, indeed, very close to what a phonemic transcription would be.

The Tamil script recognizes two diphthongs and the two orthographic symbols that represent these are usually transcribed as

ai and

au. However, there are other vocalic sequences within a single syllable that are phonetically diphthongs. Firth (1934, p. xxi) speaks of these as ‘special diphthongs’—special in the sense that rather than being written with a single vowel symbol, they are made up of an orthographic sequence of vowel + <y>. They fall into two groups, namely orthographic

ey and

oy , and orthographic

aay ,

eey , and

ooy ; that is to say, two in which the first vocalic element is short, and three in which it is long. Certain generalizations emerge from these facts. Diphthongs in formal Tamil are all, in Daniel Jones terms, falling diphthongs and all are closing diphthongs. With regard to the latter feature,

au is exceptional in closing toward a back vowel. It is also of relatively infrequent occurrence. Moreover, unlike any of the others, it does not occur as the vocalic component of a monosyllabic word. Among monosyllables involving the other six are

kai, ‘hand;’

cey, ‘do;’,

poy, ‘untruth;’

vaay, ‘mouth;’

peey, ‘demon;’

pooy, ‘past participle of

poo “go.”’ These raise the issue of how such vocalic sequences should be treated at the phonological level. That is to say, in the simplest terms,

are there underlying diphthongs in Tamil? Or are such sequences all better treated as V +

y (or, in the case of the second set of Firth’s ‘special diphthongs,’

+

y)?

1 This would mean that the three items

kai, cey, and

poy would all have the structure CVC. This, to revive a term from orthodox phonemic theory, would satisfy the demands of pattern congruity and would allow all to be accommodated by the same phonological rules. Thus, in the case of root morphemes having the structure C

1VC

2, C

2 is doubled before a vowel-initial suffix, giving the following (with

kai taken to be

kay):

kayyil (locative),

ceyya (infinitive), and

poyyil (locative). These are then all of the same pattern as one finds with other consonants in the C

2 position; for example,

pallil, ‘tooth.loc;’

kaɭɭil, ‘toddy.loc;’ and

maηηil, ‘earth.loc.’Root morphemes having the structure C

1C

2 do not have doubling of C

2:

vaayil, ‘mouth;’

paalil, ‘milk.loc;’ and

vaaɭil, ‘sword.loc.’ The rules that generate these suffixed forms in formal Tamil also provide a formula to express the relation between the uninflected forms in the formal and informal varieties, in that the latter commonly have an ‘enunciative vowel’ (see Bright, 1990, pp. 86–117):

kayyi, ceyyi, pallu, vaayi, pooyi, and

paalu—where, as is apparent, the nature of this vowel is determined by the nature of the preceding consonant.

There are other generalizations to be made about diphthongs in formal Tamil. First, only ai occurs in noninitial syllables of monomorphemic word forms. Second, only ai and aay occur as suffixes, the former as the marker of accusative case and the latter as an adverbalizing suffix when added to a noun stem. It is the particularly wide privilege of occurrence of ai that makes it of particular interest in a comparison of formal and informal spoken Tamil.

It is possible to give an account of the differences between the vowel systems of the two varieties by taking the formal variety as basic and the informal as derived from it. In these terms, vowels in formal Tamil may undergo either modification or deletion in the informal variety. Such modification or deletion can reasonably be seen as related to the stress patterns of the language. The greater the degree of salience of a syllable in relation to other syllables in a word, the less likely is the vowel nucleus to undergo change or to be lost. It has been shown that unstressed i, u, and a are subject to these forces (see Keane, 2001, p. 125).

A number of analyses have concluded with regard to ai that it is subject to reduction to a short vowel in all environments except that of a word-initial syllable (or alternatively, of course, that the y of ay is subject to deletion in the same environments; see, for example, Asher, 1982, pp. 220 and 259; Balasubramanian, 1972, p. 224; and Schiffman, 1999, p. 3). While there is no explicit discussion of the issue, the roman transcription in Kumaraswami Raja and Doraswamy, 1966, and Shanmugam Pillai, 1965 and 1968, implicitly supports the same analysis. The resulting vowel has been transcribed as e and a, depending on the dialect being described, and so assuming a range of realizations from [ε] to [ә]. Examples of corresponding forms in the two varieties follow:

Formal | Informal | |

pai | payyi2 | ‘bag’ |

aiyoo | ayyoo | ‘alas’ |

manaivi | manevi | ‘wife’ |

talai | tale | ‘head’ |

veelai-y-ai | veeleye | ‘work.acc’ |

Descriptions that equate written ai with colloquial e are quite clear that the latter is a short monophthong. However, a careful experimental analysis of examples of colloquial utterances has shown diphthongs occurring in comparable environments. An explanation has been sought for the discrepancy. In this quest, one must take account of the fact that most of the accounts are based on an impressionistic analysis; that is to say that phonetically trained analysts have concluded that what they hear is a monophthong. The possibility must be allowed for that this conclusion is the result of the reduced duration of the syllable as compared with the formal style, even though the formants diverge.

An alternative hypothesis is that the effect of the presence of recording equipment has had the result that informants providing examples of utterances have modified their pronunciation in the direction of the formal style. Support for this is to be found in the fact that speakers who are ready to agree that, for instance, talai has a different realization in informal speech from its pronunciation in formal speech, will commonly, in making a written version in the Tamil script as an aid to memory in making a recording, use the written symbol for ai in word-final position, regardless of how they believe they pronounce it. This, it is argued, then leads them to produce a reading pronunciation rather than a totally natural colloquial utterance. There is support for this argument in the fact that there is no universally agreed system for writing informal Tamil in the Tamil script and in the fact that there are strict conventions taught in schools for reading from a written text.

With such thoughts in mind, other recordings, differently organized, were subjected to the same experiments. In view of its wider distribution as compared with other diphthongs in the language, these experiments focussed on ai.

METHOD

Materials were designed to elicit formal and informal utterances of a range of sentences, so that the production of the ai in each could be compared. In the formal condition, subjects were required to read sentences presented in Tamil orthography, following the standard conventions for written texts. The informal data were elicited by asking subjects to respond to prerecorded questions on the basis of pictorial stimuli, a method that had been found to produce genuinely colloquial utterances in previous work. It has the advantage of avoiding any orthographic representation, which is highly problematic given the lack of standards for writing informal Tamil, and the limitations of the script. For example, nasalized vowels, which are common in informal speech, cannot be represented as such in the orthography. The colloquial nature of the questions, which were prerecorded by a native speaker, also encouraged an informal response.

An example of a formal and informal pair is provided in the following numbered list, the first transliterated, the second an indication of the expected pronunciation. As mentioned earlier, the formal and informal varieties are distinct at all levels, and this is reflected by differences not only in the realization of what in the formal register at least is a diphthong but also in the form of the noun and the verbal inflection:

1. | kumaar | taηηiir | kotikka | vaikkiraan |

2. | kumaar | taηηi | kodikka3 | vekrãã |

| Kumar | water | boil.infin | cause.pres.3sm |

| ‘Kumar is boiling the water.’ | |

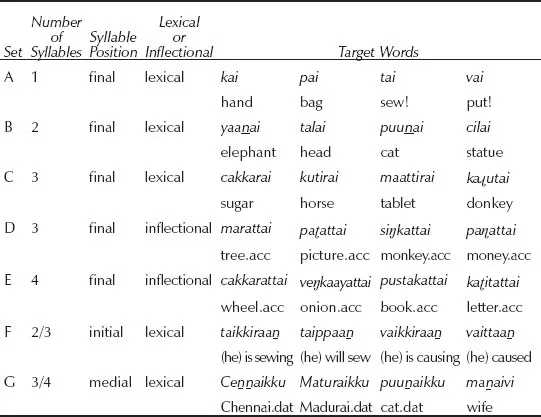

For both conditions, the stimuli were presented on a computer screen, a sentence or a picture at a time, and the subject controlled the rate of presentation by pressing the return key to move between stimuli. In the informal condition, this prompted not only presentation of the picture but also automatic playing of the relevant question. There were in all 28 target words containing ai diphthongs, equally divided between seven different categories, as illustrated in Table 7.1.

TABLE 7.1

Target Words

The different categories were chosen to investigate a possible effect of the position of the syllable containing ai—initial, medial, or final. Word length...