This is a test

- 227 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Children's Drawings As Diagnostic Aids

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Shows the ways in which self-portraits and other pictures drawn by youngsters reflect their personality traits, cognitive development, Emotional Stability, And Family Background.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Children's Drawings As Diagnostic Aids by Joseph H. Di Leo in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Psychotherapy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

An Overview

1

REPRESENTATIONAL DRAWING STARTS WITH CIRCLES

What do preschool children draw?

Does the primitive circle represent only the head?

Quantitative and qualitative characteristics

What do preschool children draw?

As the child approaches age three, his kinesthetic drawings show an increasing tendency to make circular strokes. At first these may be continuous and skeinlike. Soon, they will become discrete circles and, in these, the child will discover that he has represented perhaps, a head. The breakthrough has occurred. Kinesthetic drawing, the joy of recording movement, will gradually give way to the greater satisfaction of creating representational form. Like his prehistoric ancestor, the child has discovered that he can make an image. In the individual, as in the race, the origin of art can be traced to chance.

Universality of the phenomenon has given rise to much speculation as to the significance of the circle as the earliest expression of representational art.

Interpretation seems to vary according to the observer’s bias. One might see it as a function of coordination resulting in turn from maturational development of the nervous system, so that the three- year-old is able to do what he could not do earlier.

Another might interpret the phenomenon psychoanalytically, as expressing the child’s first perception, his mother’s breasts.

The fact is that the circle is the simplest pattern, the universally selected pattern, and the most common form in nature. The child will continue to use it as he represents a variety of perceptions —head, eyes, mouth, trunk, ears, and even hair.

Children who have never seen a woman’s breasts, those abandoned or separated at birth from their mothers and reared in institutions, will likewise begin their representational graphic activity with the circle. Might it be a manifestation of the collective unconscious? (Figures 1, 2, 3)

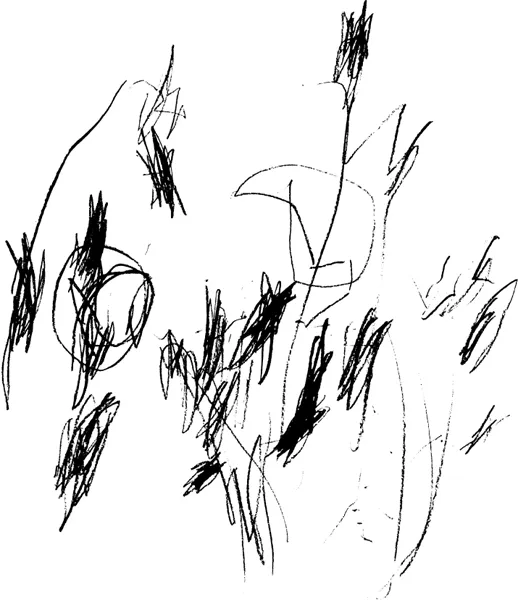

FIGURE 1

Spontaneous drawing by a girl of 30 months. She has been living in an institution since birth, has been artificially fed, and has never seen a breast.

FIGURE 2

Transitional. Predominantly kinesthetic with some representational elements. 39-month female, premature breech delivery (birth weight 2 lbs. 2 oz.). Artificially fed since birth. Institution child. Note circles.

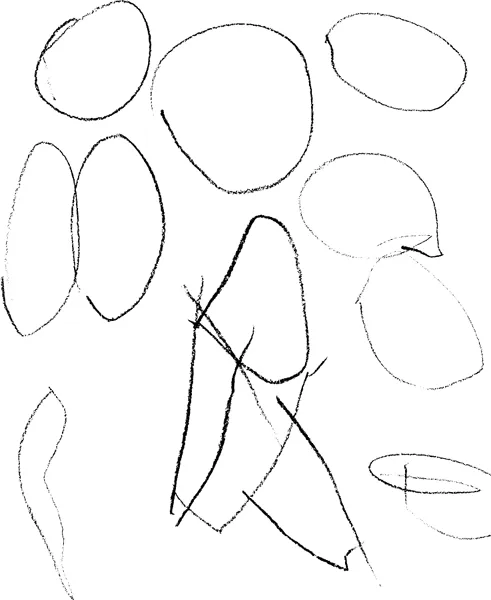

FIGURE 3

Spontaneous drawing by a girl of 3 years 9 months. Artificially fed since birth. Placed from institution into foster home at age 1 month. Representational drawing, mostly circles.

Imagination frees the spirit from

the bonds of reality

The child, in his early attempts at representation, does not try to draw the object as it looks but the idea, the internal model, and produces a schematic reduction to essentials. Luquet termed this intellectual realism to distinguish it from the visual realism of the adult. Great artists of our time, notably Klee, have sought to recapture the memory images of childhood and the child’s capacity to picture some of what he knows.

Piaget observed that the transition from intellectual realism to visual realism is not limited to drawing but characterizes all of the child’s mental processes—the young child’s reality is of his own mental construction, and the child’s vision is distorted by his ideas.

C. Ricci (Italy), writing in 1885, noted how young children drew what they knew existed and not what was actually seen, and illustrated the principle with fascinating reproductions of drawings showing men visible through the hulls of ships, men on horseback astride but showing both legs, and a bell-ringer inside the bell- tower. What exists must be shown.

In analyzing the first stage in development of the figurative arts, I. Piotrowska (Poland) tells how children draw the known and not the seen reality, and how the figures are exaggerated by affective and expressive influences.

H. Eng (Norway) studied the drawings of her niece from the earliest scribblings to age eight. Her observations confirmed those of investigators in other countries—that the child’s first recognizable drawing is usually a human figure, and that the child draws what he knows and not what is seen.

The child’s drawing of a person is identical whether a person or other model is before him or whether he draws from memory.

M. Prudhommeau (France) states that the child does not draw the object as it is but draws his idea of it, that is, his modèle interne.

W. Wolff (U.S.A.), noting that children’s art refers to an inner realism, added an important dimension to our understanding by indicating that a most important element, the emotional factor, influences the child’s concept and drawings.

H. G. Spearing (England) found that children do not try to draw what they can actually see, but what they remember; and that it is only later that they will be influenced by what is actually seen and by suggestion, instruction, and direction.

H. Read agreed that what is drawn is a mental impression rather than a visual observation. He, too, noted that the representation is not purely intellectual but imbued with emotional elements.

On pages 103 and 104 of my book Young Children and Their Drawings, the reader may see an amusing example of “drawing what is known to exist.” A preschool boy, having drawn what he called a cow, turned the paper over to draw the tail behind, much like Spearing’s description of the little girl who, on being given a picture of a bird in profile, asked why it had only one eye, then “not satisfied with the explanation, she turned the paper over and drew the other eye.”

I have offered some representative opinions in support of the important principle that drawings by young children are representations and not reproduction, that they express an inner and not a visual realism. The drawings make a statement about the child himself and less about the object drawn. The image is imbued with affective as well as cognitive elements.

Yet R. Arnheim claims that the child draws what he sees. It seems to me that this contrastingly expressed view is only in semantic conflict with that of the others mentioned. The conflict revolves about the word “sees.” If I am interpreting him correctly, Arnheim does not use the word “see” to indicate a mere sensation. He does not equate the retina...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Part One: An Overview

- Part Two: Family Drawings

- Part Three: Handicapped Children’s Drawings

- Part Four: Learning Disability

- Epilogue

- Appendix

- References

- Index of names

- Index of subjects