![]()

1

What is Strategic

Environmental Assessment?

In Chapter 1, the origins and development to date of strategic environmental assessment (SEA) are summarized. Furthermore, current SEA understanding and perceived benefits arising from SEA are outlined. The substantive focus of SEA is explained and its differences from project environmental impact assessment (EIA) are depicted. Furthermore, SEA's rationale is established. Why and when SEA is effective in improving the consideration of the environmental component in policy, plan and programme (PPP) making are explored. Context conditions for effective SEA are identified and, finally, a summary of the main points is provided.

Introduction

General environmental assessment requirements in public decision-making were first introduced in the US in 1970, based on the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), covering ‘major Federal actions’ (United States Government, 1969). While in 1978 the President's Council on Environmental Quality defined these ‘actions’ to include regulations, plans, policies, procedures, legislative proposals and programmes (Wood, 2002; Wright, 2006), in practice, NEPA-based assessment mainly revolved around project proposals.

Following NEPA, other countries started to establish environmental assessment requirements (see Dalal-Clayton and Sadler, 2005), such as: Canada (based on the Federal Environmental Assessment Review Process of 1973); Australia (based on the Commonwealth Government's Environment Protection [Impact of Proposals] Act of 1974); West Germany (based on the Principles for Assessing the Environmental Compatibility of Public Measures of the Federation of 1975); and France (based on the Law on the Protection of the Natural Environment of 1976). However, at the early stages of its development, in many systems, environmental assessment was used only occasionally rather than systematically. Furthermore, similarly to US practice, throughout the 1970s and 1980s, in most countries, environmental assessment was applied mainly to project planning (Fischer, 2002a). Finally, international aid organizations and development banks, such as the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the World Bank started to promote environmental assessment application and training, particularly in developing countries in the 1980s (see, for example, Dusik et al, 2003; OECD, 2006; World Bank Group, 2006).

During the 1980s, within the environmental assessment literature, increasingly, a distinction was made between project and higher tiers of decision-making. In the member states of the European Union (EU), this distinction became formalized through the introduction of environmental impact assessment in 1985, based on Directive 85/337/EEC (European Commission, 1985), covering projects only. In a European context, therefore, the term EIA became used for project assessment. Due to a growing perception that environmental consequences also needed to be considered in decision-making above the project level, strategic environmental assessment was introduced in the second half of the 1980s (Wood and Djeddour, 1992). The decision-making tiers to which SEA is applied have become widely referred to as policies, plans and programmes (PPPs).

Initially, SEA was mainly thought of in terms of the application of project EIA principles to PPPs (Fischer and Seaton, 2002). However, subsequently different interpretations emerged that were connected in particular with:

• the different geographical and time scales of SEA and EIA (Lee and Walsh, 1992);

• the different levels of detail at strategic and project tiers (Partidário and Fischer, 2004);

• the different ways in which strategic decision processes are organized, when compared with project planning (Kørnøv and Thissen, 2000; Nitz and Brown, 2001).

SEA can be described as having the following three main meanings:

• SEA is a systematic decision support process, aiming to ensure that environmental and possibly other sustainability aspects are considered in PPP making. In this context, SEA may support, first, public planning authorities and private bodies (including international aid organizations/development banks) to conduct:

– structured, rigorous, participative, open and transparent EIA-based processes, particularly to plans and programmes;

– participative, open and transparent, possibly non-EIA-based flexible processes to policies/visions and policy plans.

Second, SEA may support cabinet-type decision-making, working as a flexible (non-EIA based) assessment instrument that is applied to legislative proposals and other PPPs.

• SEA is an evidence-based instrument, aiming to add scientific rigour to PPP making by applying a range of assessment methods and techniques.

• SEA provides for a structured decision framework, aiming to support more effective and efficient decision-making, sustainable development and improved governance by establishing a substantive focus, for example, in terms of the issues and alternatives to be considered at different systematic tiers and levels.

Within this book, SEA for public planning and private bodies is referred to as ‘administration-led SEA’, while SEA for cabinet-type decision-making is referred to as ‘cabinet SEA’. The main focus of the book is on the former, namely, SEA conducted by public planning authorities and private bodies (including international aid organizations/development banks) because this is where SEA is mainly conducted and required globally, and because there is a much wider range of practical experiences with administration-led SEA than with cabinet SEA.

To date, SEA has been applied in a wide range of different situations, including trade agreements, funding programmes, economic development plans, spatial/land use and sectoral (for example, transport, energy, waste, water) PPPs. In this book, a wide range of practice examples are brought forward, mainly from spatial/land use, transport and electricity transmission planning. Numerous examples for other SEA applications can be found in the professional literature, for example for waste management (Arbter, 2005; Verheem, 1996), trade (Kirkpatrick and George, 2004), oil and gas extraction (DTI, 2001), economic development plans (Fischer, 2003c), wind farms (Kleinschmidt and Wagner, 1996; for offshore windfarms see Schomerus et al, 2006), water/flood management (DEFRA, 2004) and funding programmes (Ward et al, 2005). Finally, policy SEA has been the main focus of two recent publications, including Sadler (2005) and the World Bank (2005).

Currently, probably the best-known SEA ‘framework law that establishes a minimum common procedure for certain official plans and programmes’ (Dalal-Clayton and Sadler, 2005, p37) is the European Directive 2001/42/EC on the assessment of the effects of certain plans and programmes on the environment (‘SEA Directive’; European Commission, 2001b). This Directive advocates the application of a systematic, pro-active EIA-based and participative process that is prepared with a view to avoiding unnecessary duplication in tiered assessment practice. In this context, however, policies and cabinet decision-making are not mentioned. At the heart of a Directive-based SEA process is the preparation of an environmental report, which is supposed to:

• portray the relationship with other PPPs;

• identify the significant impacts of different alternatives on certain environmental aspects;

• explain how the SEA was considered in decision-making;

• provide information on the reasons for the choice of a certain alternative.

Furthermore a non-technical summary needs to be prepared and monitoring arrangements for significant environmental impacts need to be put into place.

The implementation and transposition status of the SEA Directive in EU member states is described in Chapter 5. In its short lifetime to date, the SEA Directive has not only had an impact on EU member states, but also within a wider international context. It has been a reference point for practice, for example, in Asia, Africa and South America. Furthermore, the Kiev protocol to the Espoo Convention (UNECE, 2003) on trans-boundary SEA formulates almost identical requirements to the Directive, though it also explicitly mentions the possibility of applying SEA at the policy level. This protocol and the associated Resource Manual (UNECE, 2006) are likely to enhance SEA application in United Nations Economic Council for Europe (UNECE) states outside the EU.

The SEA process

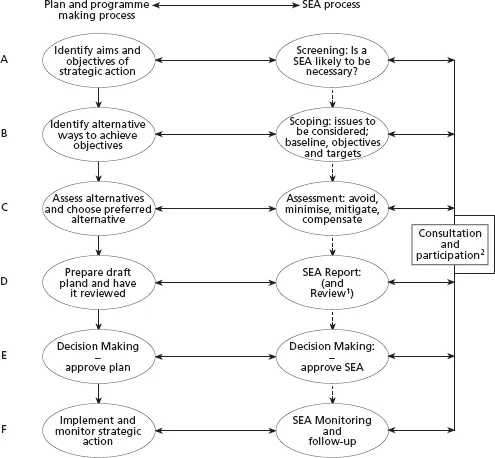

Figure 1.1 shows an SEA Directive-based assessment process. This is EIA based and linked to plan and programme making stages in a continuous and integrated decision flow. This process is objectivesled (namely, trying to influence PPP making so that certain objectives can be reached) and baseline-led (namely, relying on baseline data to be able to make reliable projections in assessment), and reflects ideas of instrumental rationality (Faludi, 1973).

Notes: 1 not explicitly required by the Directive

2 according to the Directive, at least at scoping and report stages of the SEA process

Source: Thomas Fischer; see also European Commission (2006)

Figure 1.1 EC SEA Directive-based process for improving plan and programme making

If applied in the way shown in Figure 1.1, the SEA process is thought to be able to influence the underlying plan and programme making process, with a view to improving it from an environmental perspective. Furthermore, an SEA that is applied in this manner may reshape the plan and programme decision flow, supporting not only the consideration of environmental issues at each stage of the process, but also leading to improved transparency and governance (Kidd and Fischer, 2007). The generic SEA process is explained in further detail in Chapter 2.

Describing non-EIA-based SEA, applied in policy and cabinet decision-making situations (at times also referred to as ‘policy assessment’-based SEA), is not as straightforward, as this is normally portrayed as being flexible, adaptable and at times communicative (reflecting ideas of communicative rationality; see Healey, 1997). However, even non-EIA-based SEA is normally perceived as being a systematic process, which may take different forms (see Kørnøv and Thissen, 2000). To date, attempts to define non-EIA-based SEA in a generic way have either led to a somewhat blurred picture of SEA or, ironically, have made it look similar to EIA-based SEA. This was described by Fischer (2003a), based on observations made by Tonn et al (2000) and Nielsson and Dalkmann (2001). Generally speaking, non-EIA-based assessment approaches are considered to be less methodologically rigorous than EIA-based processes, and descriptions of non-EIA-based SEA frequently mention the following core elements:

• Specifying the issue (problem identification);

• Goal setting (what are aims, objectives and targets);

• Information collection;

• Information processing and consideration of alternatives;

• Decision-making;

• Implementation.

Whilst there are a range of non-EIA-based systems (see Chapter 4), there is currently hardly any empirical evidence available for what makes non-EIA process-based SEA effective. In this context, research is urgently needed.

Current understanding and

perceived benefits from SEA

SEA's main aim is to ensure due consideration is given to environmental and possibly other sustainability aspects in PPP making above the project level. Furthermore, it is supposed to support the development of more transparent strategic decisions. It attempts to provide relevant and reliable information for those involved in PPP making in an effective and timely manner. As mentioned above, the exact form of SEA will depend on the specific situation and context it is applied in. Procedurally, differences are particularly evident between administration-led SEA and cabinet SEA. Regarding the substantive focus (that is, the issues and alternatives to be considered), differences may exist between different administrative levels (for example, national, regional, local), strategic tiers (for example, policy, plan and programme) and sectors (for example, land-use, transport, energy, waste, water). While certain key elements are likely to be reflected in every SEA system, others will differ depending on established planning and assessment practices, as well as on the specific traditions of the organizations preparing PPPs and SEAs. Based on what has been laid out in the previous section, Box 1.1 presents an up-to-date definition of SEA.

Generally speaking, a range of benefits are supposed to result from the application of SEA. In this context, SEA aims at supporting PPP processes, leading to environmentally sound and sustainable development. Furthermore, it attempts to strengthen strategic processes, improving good governance and building public trust and confidence into strategic decision-making. Ultimately, it is hoped that SEA can lead to savings in time and money by avoiding costly mistakes, leading to a better quality of life. Box 1.2 shows those ...