![]()

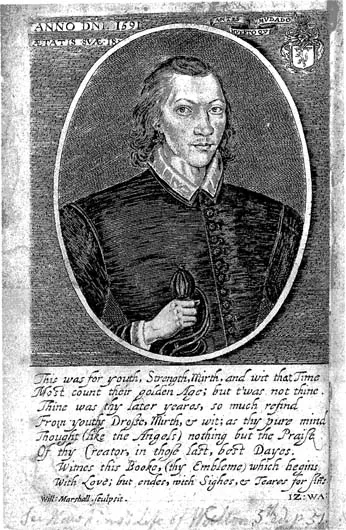

John Donne, from an engraving by William Marshall (after a painting by Nicholas Hilliard?), the frontispiece to Poems, 1635. Bodleian Library, University of Oxford.

CHAPTER ONE

John Donne

Life

More is known about Donne, the man, than about any other poet before Milton, and what is known adds up to a story of someone with an uneasy relation to the world. It is not that his life was unusually hard, but that with all his exceptional social and intellectual gifts, with all his ambition to employ them in a worldly career, the circumstances and events of his life thwarted his fitting easily into public life and becoming a servant of the state like his friend Sir Henry Wotton. He was born a Catholic when Catholics were persecuted as enemies of the state; his marriage cast him out of the world into which he had managed to find an entry; after thirteen years of ‘exile’ from the world, he was ordained in the Church of England and there certainly became at last a pillar of the establishment, but only by an institutionalizing of his estrangement from the world and bringing the demands of another world to bear on this one. Alienation from the world is not all there is to Donne’s poetry by any means. But it is a persistent feature, even the ground note of his poetry, a note always somewhere behind its peculiar intensity. In Donne, interiority takes the shape of isolation and its attendant anxieties and exaltations.

Donne was set apart from the world he later tried to join by his Catholic upbringing. He was born in 1572. His father, John Donne, was a prosperous London merchant, an iron-monger with claims to descent from Welsh gentry. He died in 1576, when Donne was four. Soon after, Donne’s mother married John Syminges, a successful doctor in London. After he died in 1588, she took a third husband, Richard Rainsford, in 1590 or 1591. There is no conclusive evidence that John Donne senior or John Syminges were Catholics. They probably were but must have been discreet about it. Donne’s mother, on the other hand, came from the heroic wing of English Catholicism. Elizabeth Donne was grandniece of the Catholic martyr, Sir Thomas More. Her father, John Heywood, a writer of interludes and epigrams, went into exile in 1564 rather than make his peace with Queen Elizabeth’s Protestant settlement of the English Church. Two of her brothers, Ellis and Jasper, became Jesuits. Jasper, who led a Jesuit mission to England in the early 1580s, was imprisoned in the Tower and narrowly escaped a hideous martyrdom. And there were other members of the family who suffered for their faith. After the death of Dr Syminges, Elizabeth Donne became known as a recusant, and soon after her third marriage she settled with her husband in Antwerp to escape the penalties imposed on Catholics in England.1

Catholics under Queen Elizabeth were at first penalized for nonconformity with the state church. They were barred from public office and fined for non-attendance at church services. For about a decade the government hoped that its measures were not so severe as to provoke desperate resistance but severe enough to push all but the firmest towards the Church of England. After the rebellion of the Northern Catholics in 1569–70 and the papal bull of 1570 excommunicating Elizabeth as a heretic and therefore a tyrant and usurper to whom no allegiance could be owed, the issue became a matter of treason. The Pope urged Elizabeth’s subjects to dethrone her, and the government’s response was to treat the Catholic minority as a fifth column waiting for a propitious moment. To the government anyway, propitious moments must have seemed almost continuous in the 1580s, what with plots involving Mary Queen of Scots, Elizabeth’s Catholic cousin and prisoner, and with hostilities with Catholic Spain mounting to open war and attempts at invasion. In these circumstances the Elizabethan state did not show its devoutness by burning heretics but exhibited its power or its fear by hanging, drawing and quartering as traitors both Catholic priests found guilty of seducing the Queen’s subjects from their obedience to their sovereign and those they seduced. Even to remain a staunchly Catholic layman was financially ruinous. Those attending Mass were fined a hundred marks; recusants, that is those refusing to attend Church of England services, were fined twenty pounds a month. The fines were a welcome source of revenue and a system of government spies, the detestable poursuivants mentioned in Donne’s ‘Satire IV, ll. 214–17, was set up to exact them.2

Meanwhile a Jesuit missionary campaign from the English Colleges on the Continent was bent on a heroic attempt to recover England for Rome. The campaign may have braced the resistance of some and must have sharpened the anguish of being Catholic for the community as a whole. Despite persecution, most English Catholics wished nothing more than to be loyal subjects of the Queen, and most detested the Pope’s claim to depose her. Many, perhaps most, of the English Catholic community found it possible to live with attending Church of England services as demanded by law and so evade its penalties. Some of them may have found it possible to take the Oath of Supremacy and accept Elizabeth as head of the English Church. The Jesuit missionaries came to force a more rigorous faith on the conscience of Catholic England, a choice of political loyalty to the Pope rather than to Elizabeth and an end to compromise with the state religion. In doing so they aroused the hostility, not only of the patriotic and easygoing among the laity, but also of the secular priests (that is, priests who were not Jesuits or in monastic orders) who knew the temper of the Catholic community as a whole and did not think it possible to change it in the direction of heroic intransigence, and who, moreover, did not wish to give their persecutors a reason for harsher measures.

Did Donne grow up under a reign of terror? In thirty-three years of Elizabeth’s reign after 1570, 250 died for their Catholicism (some from imprisonment rather than execution). This is a negligible toll by twentieth-century standards and fairly mild in comparison with the burning of 300 Protestants in five years under Mary Tudor, though the tortures used by Elizabeth’s government to find out and kill its enemies rightly got it an evil name in Catholic countries. Some of the reports of those who submitted to the laws that demanded attendance at the services of the established church suggest carelessness and contempt rather than timid acquiescence, let alone fear. Whether all this implies the moderation or simply the limited power of the Elizabethan state to cow its subjects, the degree of anxiety felt among the Catholic community would depend on where one was placed, whether on the heroic wing ready for martyrdom or among the discreet, compromising or careless. It is possible that Donne’s family was divided, his father and first step-father preferring to lie low, his mother, with the martyrs among her kinsmen, less willing to compromise and more willing to take risks for her faith. This is speculation, but the idea that Donne was brought up in an atmosphere of unqualified Catholic ardour with a vocation for martyrdom ignores the complexity of Catholic affiliation under Elizabeth. That being a Catholic may from the start have been a divided thing bears, as we shall see, on Donne’s later dividing himself from the church he was born into and his going over to the Protestants.

Nevertheless, Donne’s childhood and youth were certainly marked by a Catholicism that set itself against the religion of the Elizabethan state. For this we have Donne’s own account in the Preface to his Pseudo-Martyr.

I had longer work to doe then many other men; for I was at first to blot out, certaine impressions of the Romane religion, and to wrastle both against the examples and against the reasons, by which some hold was taken; and some anticipations early layde vpon my conscience, both by Persons who by nature had a power and superiority ouer my will, and others who by their learning and good life, seem’d to me iustly to claime an interest for the guiding, and rectifying of mine understanding in these matters.3

Before he went to university, he was educated privately by a tutor who, Bald says, we may assume ‘without question’ to be ‘a good Catholic, perhaps a seminary priest’.4 At Oxford, he matriculated from Hart Hall, a college without a chapel and consequently popular with Catholics because it was hard to check on attendance at services. He went up young and made out that he was even younger than he was by a year, eleven not twelve. This too was to evade the legislation meant to keep Catholics out of higher education: university statutes required that those taking degrees should swear to the Oath of Supremacy and that those matriculating at sixteen or older should subscribe not only to the Oath of Supremacy but also to the Thirty-Nine Articles of belief imposed by the Church of England. By entering young and lying about his age, Donne might gain a university education, if not a degree, without renouncing his Catholicism.5

According to his seventeenth-century biographer Izaak Walton, Donne was transplanted from Oxford to Cambridge at fourteen, and then at seventeen went up to Lincoln’s Inn to study law.6 The records show, however, that he entered Lincoln’s Inn in 1592, when he was twenty, and would according to the prescribed course have entered Thavies Inn a year earlier. Bald, noting the discrepancy, suggests that Donne may have gone on his travels to Italy and Spain between 1589 and 1591.7 According to Walton, again, when Donne entered the Inns of Court, his mother ‘and those to whose care he was committed, were watchful to improve his knowledge, and to that end appointed him Tutors in the Mathematicks, and all the Liberal Sciences to attend him. But with these Arts they were advised to instil particular principles of the Romish Church.’8

In spite of all these precautions, Donne began to move away from Catholicism during his time at the Inns of Court. It is probable that as a student at Oxford and Cambridge he had already entered a freer, more worldly society than that in which he had been brought up, if some of the friendships of his later life, such as those with Henry Wotton and Henry Goodyer, were begun then.9 About the Inns of Court, there is no doubt. These were conspicuously an upper-class society. Some of its members, it is true, prepared themselves for a career in the law. But Donne separates himself from that sort of student in ‘Satire II’ in Coscus, a caricature of drudgery and small chicane. He must have aligned himself with the sons of gentry who prepared themselves for a career in government service with a training in the law. He would have found it easier to support that character when in 1593 he came into the inheritance left by his father and so was freer of his mother’s influence. The Inns of Court, gathering together those ‘of study and play made strange hermaphrodites’ (‘An Epithalamion Made at Lincoln’s Inn’, l. 30), were also a school of wit, smart, citified, satirical, scabrous. It was in this company that Donne invented himself as Jack Donne, the author of the first and second Satires, of many of his Elegies and ‘An Epithalamion Made at Lincoln’s Inn’, and of some of the early verse letters that carry on the business of friendship by means of complimentary poems about his correspondents’ poems. Outside his poetry, the character of Jack Donne comes over in the description in the Chronicles of his contemporary Sir Richard Baker: ‘not dissolute but very neat; a great visiter of Ladies, a great frequenter of Playes, a great writer of conceited verses’.10 ‘Dissolute’ here means slipshod. Jack Donne was a dandy.

While Donne was finding himself as an entertaining companion and fine spirit among those who expected to play a part in the world, he was naturally much occupied with the Catholicism that kept him out of it. A dreadful reminder of that was the death in prison of his younger brother, Henry, in 1593. He had gone up to Oxford with Donne and followed him to the Inns of Court. Henry had been caught harbouring a priest; the priest was executed in the usual vile manner, while Henry died in pri...