![]()

1

Green Economics: Economics

for People and the Planet

Economic man is fit, mobile, able-bodied, unencumbered by domestic or other responsibilities. The goods he consumes appear to him as finished products or services and disappear from his view on disposal or dismissal. He has no responsibility for the life-cycle of those goods or services any more than he questions the source of the air he breathes or the disposal of his excreta... Like Oscar Wilde's Dorian Gray, economic man appears to exist in a smoothly functioning world, while the portrait in the attic represents his real social, biological and ecological condition.

Mary Mellor, ‘Challenging Economic Boundaries: Ecofeminist

Political Economy’, 2006

Over the past five years or so the issue of climate change has moved from a peripheral concern of scientists and environmentalists to being a central issue in global policy making. It was the realization that the way our economy operates is causing pollution on a scale that threatens our very survival that first motivated the development of a green approach to the economy. We are in an era of declining oil supplies and increased competition for those that remain. This raises concerns about the future of an economy that is entirely dependent on oil and a wider recognition of the importance of using our limited resources wisely. This was the other motivation for the development of green economics. In addition, green economists have been concerned about the way an economic system based on competition has led to widening inequalities between rich and poor on a global as well as a national scale, and the inevitable tension and conflict this inequality generates.

At last, these three issues are reaching the mainstream of political debate. This increased attention is being driven mainly by public opinion and by campaigners such as in the Make Poverty History campaign or the Climate Chaos Campaign. Politicians appear to have been caught on the hop and their responses seem both half-hearted and inadequate. In this context, green economics has for the past 30 years been developing policy based on a recognition of planetary limits and the importance of using resources wisely and justly; these insights are of crucial importance.

Why green economics?

I have called this chapter ‘Economics for People and the Planet’, and that is a glib phrase which green economists frequently use to describe how their proposal for the world's economy is different. It is really shorthand for expressing a need to move beyond the narrow view of the economy as it is currently organized. So many perspectives are never considered by a system of economics that privileges white, wealthy, Western men. The way the global economy is organized can be seen as an extension of a colonial system, whereby the resources and people of most of the planet are harnessed to improve the living standards of the minority of people who live in the privileged West. On the one hand, the rights of people living in the global South to an equal share in the planet's resources should be respected. On the other, their approach to economics, especially that of indigenous societies that have managed to survive within their environments for thousands of years, has much to recommend it and much we may learn from.

Even within Western societies there are gross inequalities between people. As the data in Box 1.1 show, inequality is growing steadily in the UK, and this is mirrored in other countries, including the rapidly developing economies in the South.1 The system of patriarchy has ensured that the majority of resources are controlled by men. Most of the world's poor are women. The male dominance of the economy has resulted in a situation where women form 70 per cent of the world's poor and own only 1 per cent of the world's assets (Amnesty International). According to the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) (2005), on a global basis women earn only 50 per cent of what men earn. And in spite of equal pay legislation in the UK and US the pay gap between the genders persists.

Policy makers are happy to use the word ‘exploit’ when talking about resources such as oil or minerals. Yet for green economists exploitation of the planet's resources is as unacceptable as exploitation of the people who live on it. The failure to respect the planet has led to problems as diverse as climate change and desertification. In order to address these problems green economists suggest that we need a completely different attitude towards meeting our needs, one which involves respecting ecology and living in balance with the planet.

Another short phrase that encapsulates something important about green economics is ‘beyond supply and demand to meeting people's needs.’ This contains an explicit criticism of the discipline of economics for its obsession with graphs and mathematics and its inability to look out of the window and see what is really happening in the world. Green economics begins with people and their concerns rather than with theories or mathematical constructions of reality. Conventional economics will provide a graph with two straight lines representing ‘supply’ and ‘demand’ and then apply this to the complex relationships entailed by the production and exchange of goods. Green economics calls for a richer and deeper understanding of people, their relationships, and how they behave and are motivated. The ‘needs’ we are concerned about are not merely physical needs but also psychological and spiritual needs.

BOX 1.1 INEQUALITY IN THE UK, 1994–2004

- Since 1997, the richest have continued to get richer. The richest 1 per cent of the population has increased its share of national income from around 6 per cent in 1980 to 13 per cent in 1999.

- Wealth distribution is more unequal than income distribution, and has continued to get more unequal in the last decade. Between 1990 and 2000 the percentage of wealth held by the wealthiest 10 per cent of the population increased from 47 per cent to 54 per cent.

- Although the gender pay gap has narrowed, only very slow progress has been made since 1994. In 1994 women in full-time work earned on average 79.5 per cent of what men earned; by 2003 this had only increased to 82 per cent.

- Deprived communities suffer the worst effects of environmental degradation. Industrial sites are disproportionately located in deprived areas: in 2003, there were five times as many sites in the wards containing the most deprived 10 per cent of the population, and seven times as many emission sources, than in wards with the least deprived 10 per cent.

Source: ‘State of the Nation’, Institute for Public Policy Research, 2004.

The word ‘holism’ sums up the way in which we have to learn to see the big picture when making economic decisions. The absence of holistic thinking is clear in modern policy making, where crime is punished by incarceration without attempting to understand how an economic system that dangles tempting baubles in front of those who cannot afford them, and deprives them of the means of meeting their deeper needs, is simply generating this crime. A similar comment can be made in the case of health, where pollution creates ill health which is then cured by producing pharmaceuticals, the production of which generates more pollution. From a green perspective we need to see the whole picture before we can solve any of these problems.

Green economics also extends the circle of concern beyond our single species to consider the whole system of planet Earth with all its complex ecology and its diverse species. As an illustration of the narrowness of the current approach to policy making we can use the thought experiment of the Parliament of All Beings. We begin by considering a national parliament in the UK or the US, which is made up of representatives of a significant number of people in those countries, only excluding those who could not or will not vote or whose votes do not translate into seats. Now we imagine a world parliament, where each country sends a number of representatives so that all countries’ interests are equally represented. We now have a much broader-based and democratic way of deciding whether the solutions to Iraq's problems will be solved by a US invasion, or about policies to tackle climate change. But now we need to extend this further, to include all the other species with whom we share this planet in our decision making. We need a representative from the deep-sea fish, the deciduous trees, the Arctic mammals, and so on. If we imagine putting to the vote in such a parliament the issue of our human wish to increase the number of nuclear power stations, we begin to see how narrow our current decision making structures are. In the case of most of what we do for economic reasons we would have just one vote against the collected votes of all the other species of planet Earth.

Photo 1.1 The men who devised the existing financial system: US Secretary of the Treasury Morgenthau addressing the opening meeting of the

Bretton Woods Conference, 8 July 1944

Source: Photo from the US National Archives made available via the IMF website

The lesson of ecology is that, as species of the planet, we are all connected in a web of life. A Buddhist parable brings to life this rather stark and scientific lesson from ecology. During his meditation a devotee fantasizes that he is eating a leg of lamb, an act proscribed by Buddhism where a strict adherence to vegetarianism is required. His spiritual master suggests that when this fantasy comes to him he draws a cross on the leg of lamb. The devotee follows the advice and, on returning to self-consciousness, is amazed to find the cross on his own arm. A more prosaic way of reaching the same sense of connection is to think about a time when you might have hit an animal or bird when driving your car. The sense of shock and horror that you have destroyed something so precious is the same, no matter how insignificant the animal appears.

This is the first lesson that green economics draws from ecology: that we cannot please ourselves without considering the consequences of what we are doing for the rest of our ecosystem. The other lesson is about adapting to the environment we find ourselves in, rather than trying to force the environment to adapt to us. It is a sense that forcing the planet as a whole to accept an impossibly high burden because of our excessive consumption that is making the lessons of ecology increasingly pressing. The solution proposed by green economics is bioregionalism. At a conference organized by Land for People in 1999, Robin Harper, the Green Party's first Scottish MP said ‘We need to move towards the idea of ecological development: the economy should be seen as a subset of the ecosystem, not the other way around.’ This sentence sums up what a bioregional economy would entail.

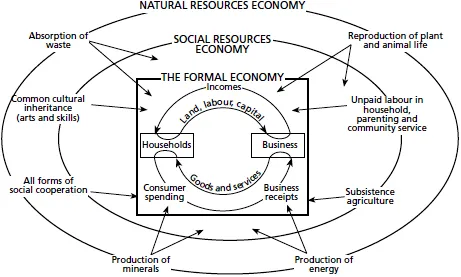

Figure 1.1 illustrates how green economics views the formal economy as embedded within a system of social structures and only a very small part of economic activity. For mainstream economists the only part of the diagram that matters is the ‘formal economy’ which they call the ‘circular flow’. They ignore the social and environmental setting within which these exchanges between households and business take place. But in reality these transactions are embedded within social relationships, and these in turn are enclosed within the planet, which is itself a closed system. It is when we fail to recognize these complex interreactions that things go off course. The diagram also illustrates the injustice inherent in the allocation of rewards within a capitalist economy, which only values what is exchanged in the monetary economy. As Mary Mellor has written, ‘The valued economy is a transcendent social form that has gained its power and ascendancy through the marginalisation and exploitation of women, colonised peoples, waged labour and the natural world increasingly on a global scale.’ It is clear from this sort of understanding that green economics is also raising difficult and radical political questions.

What is green economics?

Green economics is distinct from the dominant economic paradigm as practised by politicians and taught in the universities in three main ways:

- 1 It is inherently concerned with social justice. For mainstream economics ‘welfare economics’ is an add-on, a minor part of the discipline which is only considered peripherally. For a green economist equality and justice are at the heart of what we do and take precedence over considerations such as efficiency. Many of the contributors to green economics have a history of work in development economics, and those who do not are equally concerned to forge an international economy that addresses the concerns of all the world's peoples equally.

- 2 Green economics has emerged from environmental campaigners and green politicians because of their need for it. It has grown from the bottom up and from those who are building a sustainable economy in practice rather than from abstract theories.

- 3 Green economics is not, as yet, an academic discipline with a major place in the universities. In fact, this is the first book which has attempted to pull together the various contributions to this field into a coherent whole. The explanation for this is not that green economics has little to offer (as I hope the following pages will show); rather it is that academic debate around economics and, some would argue, the role of the university itself, has been captured by the globalized economic system, whose dominance is a threat to the environment. The motivations of this system are incompatible with the message of green economics – hence the tension.

Figure 1.1 Widening the consideration of economics beyond the classical economists’ ‘circular flow’

Source: F. Hutchinson, M. Mellor and W. Olsen (2002) The Politics of Money: Towards Sustainability and Economic Democracy, London: Pluto.

The obvious problems being caused by economic growth have not been ignored by academics: they were noticed by some in the economics profession, who then attempted to incorporate these concerns into their discipline. This led to the development of environmental economics, and also the related study of natural-resource economics. Conventional economics considers environmental impact to be an ‘externality’, something outside its concern. Environmental economists were keen to bring these negative impacts back within the discipline. However, they still approached the subject in a scientific and measurement-based way, for example using shadow pricing to measure how much people were concerned about noise pollution or the loss of habitat. In other words, the way in which economics traditionally marginalizes or ignores something that cannot be priced was still adhered to, but the response was to attempt t...