![]()

1 Why poverty and the environment?

Many parts of the world are caught in a vicious downwards spiral: Poor people are forced to overuse environmental resources to survive from day to day, and their impoverishment of their environment further impoverishes them, making their survival ever more difficult and uncertain.

(World Commission on Environment and Development, 1987: 27)

Introduction

The quote above from perhaps the most significant international environment and development report of the twentieth century sums up a common understanding and portrayal of poverty–environment relations. This portrayal suggests that poverty and the environment are linked in a ‘vicious circle’, where poverty forces many poor people to overuse and degrade the environment on which they depend, leading to environmental destruction which in turn further exacerbates the extent and depth of poverty. Some have described this relationship as a ‘downward spiral’ – emphasizing that over time, poverty will deepen and the environment will be further degraded.

But, does poverty necessarily lead to environmental destruction? Do degraded and impoverished environmental and natural resources directly lead to poverty? Or, are there other forces at play? Is the relationship between poverty and the environment really as straightforward as the vicious circle portrayal suggests? Does it matter if the relationship is portrayed in this way?

This book suggests that it does matter. The portrayal of the relationship between poverty and the environment as a vicious circle or downward spiral directs efforts to reduce poverty or improve environmental management that may focus only on poverty reduction and/or environmental management in a narrow sense, without taking sufficient account of a multitude of mediating factors, including governance, institutional arrangements and power relationships. These ‘mediating factors’ influence how people, including poor people, have access to, and control over, the environment and natural resources. Approaches that endeavour to reduce poverty and improve environmental or natural resource management may well achieve more through improving governance, asking who has power and what institutional arrangements constrain or enable access to resources than initiatives that focus directly on poverty or the environment. Whilst it has been argued that thinking about poverty and the environment has largely moved away from the ‘vicious circle’ portrayal (Reed, 2002), there remains a need for wider adoption of frameworks and approaches that take a more nuanced approach to investigating the linkages.

Tools, approaches and frameworks exist that can be used to investigate how these mediating factors influence and interact with poverty–environment relations. Having appropriate tools and approaches to investigate and generate understanding of poverty–environment relationships is essential because of the significant dependence of many poor people in the developing world on environmental goods and services. Acknowledging and understanding this dependence is even more important in light of the world’s growing population and the increasing wealth of powerful individuals and countries who are able to gain access to huge swathes of land and other resources, at times to the detriment of those living in the affected areas. In addition, increasing awareness and experience of the impacts of climate change make understanding of the interactions between poverty and the environment even more critical.

This text provides an introduction to a range of frameworks and approaches from the social sciences that can facilitate a deeper understanding of linkages between poverty and environment. These frameworks and approaches are presented within the following areas of investigation:

• political ecology;

• institutional analysis;

• gender, development and the environment;

• livelihoods and wellbeing;

• social network analysis;

• governance.

Each chapter introduces a number of frameworks and approaches, explaining key concepts and ideas and referencing key material in the development and application of the frameworks and approaches. These frameworks and approaches have not necessarily been developed with the purpose of investigating poverty–environment relationships but have the capacity to be used for this purpose. Examples and case studies of applications of the frameworks and approaches are provided to illustrate how they have been used and what kinds of research questions they may be appropriate for answering. In addition, each chapter identifies key texts to steer readers towards deeper exploration of the theory and assumptions underlying the frameworks and approaches, as well as to further examples of their application. The key readings and the list of references have been carefully and purposefully selected to provide readers with a wide range of important sources and authors in each area reviewed. Readers are encouraged to see the lists of references as both an essential resource and as a starting point for finding further relevant literature.

The discussion of the approaches and frameworks, and the majority of the examples and case studies of their application, relate to and draw on experience in developing countries, and so the book is situated within the multidisciplinary area of Development Studies. Development Studies as an area of academic study is concerned with the normative ambition of improving people’s lives and thus has a ‘shared commitment to the practical or policy relevance of teaching and research’ related to experience ‘in “less developed countries” or “developing countries” or “the South” or “post-colonial societies” formerly known as “the Third World”’ (Sumner, 2006: 645). Development Studies is a dynamic area of academic study, reflecting the heterogeneity and changes over time in the experience of ‘development’. This is reflected in the debate and contention concerned with the classification of countries in relation to development. It is widely acknowledged that the dichotomy of ‘developed and developing’ in classifying countries is outdated and, at times, unhelpful (Harris et al., 2009). There is no one criterion universally used to categorize countries in relation to their level of ‘development’ and it is not always clear where countries should be placed (Nielsen, 2013). There is, then, broad consensus that more categories should be used, reflecting different measures of development, changes over time and different purposes of the categorization (Nielsen, 2013; Tezanos and Sumner, 2013). Whilst acknowledging the diversity of development outcomes and experience across countries and the need for more than two categories of countries, the term ‘developing country’ is used throughout this book. This is because the category of ‘developing country’ is widely understood as broadly referring to countries with a lower level of economic development and often having a higher level of direct dependence on natural resources than developed countries. This category includes many countries in Asia, Africa and Latin America.

This introductory chapter sets the scene for the book, starting with the broader debate concerning environment and development and the concept of sustainable development, i.e. can the environment be protected whilst also encouraging economic growth and reducing poverty? The chapter goes on to critically review the portrayal of poverty–environment linkages as a vicious circle and downward spiral, before examining different definitions of, and approaches to, poverty and environment. Explanations of key concepts and cross-cutting themes found within the frameworks and approaches in the following chapters are then set out. These are: institutions, social capital, gender, power, property rights and regimes, community, ‘access to and control over’ natural resources and vulnerability. The structure of the book is then explained, setting out the main themes of each chapter.

Environment and development: the debate

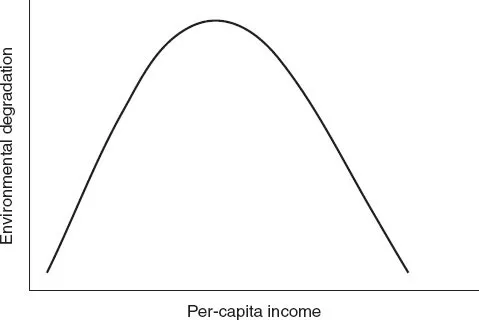

Can you protect the environment and, at the same time, also maintain and even increase development, interpreted for many years as largely equating to economic growth? This question has been the subject of much debate over decades, with evidence providing alleged support for both sides. For many in the developed and developing worlds, a view has prevailed that the environment must wait; economic growth and poverty reduction are the priorities and if the environment is degraded and polluted as a result, then cleaning it up will be less costly in the future than in the present (Clémençon, 2012). This position reflects the environmental Kuznets curve, as shown in Figure 1.1, which suggests that as income increases there comes a point at which environmental degradation will reduce and reverse, as investment in the environment and cleaner technology increases. Before that happens, environmental degradation will increase as per-capita income increases.

Of course, not everyone agrees that the Kuznets curve is correct in its depiction of the relationship between per capita income and environmental degradation (see, for example, Dasgupta et al., 2002 and Stern, 2004). Technology transfer, for example, can enable ‘tunnelling through’ the curve so that less environmental degradation is experienced than would be predicted. The nature of the relationship may also depend on which pollutants are included in the analysis, what assumptions are made about how the pollutants behave and over what period of time data is available (Stern, 2004). It is not, then, a given that the ‘environment must wait’; technology and regulations can be adopted and implemented earlier than may be implied by the Kuznets curve.

Figure 1.1 The environmental Kuznets curve.

Concern about the exploitation of natural resources as a result of development can be traced back to the nineteenth century, when Thomas Malthus voiced concern that as population grew exponentially, food production could not increase at such a rate. Debate about whether the world will run out of natural resources in the face of the increasing global population was highlighted again in the twentieth century with the publication of the report The Limits to Growth (Meadows et al., 1972). Reporting on results from computer modelling on a range of scenarios with different levels of population growth, industrialization, pollution, food production and resource depletion, the report presented two scenarios where the global system would collapse and one where stabilization could be reached. Whilst the report received much criticism, questioning the methodology and data used as well as the interpretation of the models, debate continues into the twenty-first century about whether there will be sufficient natural resources for all, with global population projected to reach 9 billion around 2050. Increasing global population is only part of the picture though, with the rate and nature of consumption in much of the developed world being far from sustainable, as well as inequitable.

The debate about the relationship between environment and development appeared to be settled and even reconciled with the coining of the concept of sustainable development, associated with the 1987 World Commission on Environment and Development report, Our Common Future. The WCED was commissioned by the United Nations in 1983 to write a report in response to concern about accelerating environment degradation and the consequences of this degradation for economic and social development. The Commission was chaired by the Norwegian Prime Minister Gro Harlem Brundtland and so the Commission and report is often referred to as the ‘Brundtland Commission’ and ‘Brundtland Report’. The definition of sustainable development given in the 1987 report is the most often cited definition in literature, policy and practice and is set out in Box 1.1.

Box 1.1 Brundtland definition of sustainable development

‘Sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. It contains within it two key concepts:

• the concept of “needs”, in particular the essential needs of the world’s poor, to which overriding priority should be given; and

• the idea of limitations imposed by the state of technology and social organization on the environment’s ability to meet present and future needs.’

(World Commission on the Environment and Development, 1987: 43)

The concept of sustainable development appears to offer hope that, at last, we can have environmental protection and economic development together. Poverty reduction, or perhaps even elimination, within and between generations is seen as fundamental to the pursuit of sustainable development, as well as sustainable environmental management. However, the concept and very idea of sustainable development has been widely critiqued, with criticisms including:

1 It is far too vague and woolly – anyone can agree with the concept and the definition given in the Brundtland Report whilst having very different understanding of what it means in practice. This has implications for policy and practice, with much being lauded in the name of sustainable development that others may well question as being at all ‘sustainable’.

2 Deep ecologists reject the concept on the grounds that it is human-centred, with little, or perhaps no, recognition of the intrinsic right of nature to exist for its own sake, rather than for the sake of humankind. The very term ‘natural resources’ suggests that nature is there for the survival of humankind, with ‘resources’ to be used and exploited as necessary.

3 At the other end of the ideological spectrum, it is argued that economic growth must continue unabated and that there are no ecological limits to growth. Not only will more natural resources be discovered, but technology and science will develop new solutions, replacing natural ‘capital’ with other forms of capital. There is, then, no need for concern, or for limits to be placed on economic growth and development.

It seems then that there are differing views as to whether it is possible to protect and enhance the condition of the environment whilst also encouraging development through economic growth. In reflecting on this, what are the implications for understanding linkages between poverty and the environment?

Poverty and the environment: the vicious circle and downward spiral

As noted at the beginning of this chapter, the relationship between poverty and the environment has traditionally been portrayed as a vicious circle, where poverty leads people to overexploit the environment, leading to degradation and consequently more poverty. The vicious circle of poverty and environmental degradation is shown in Figure 1.2.

The relationship has also been portrayed as a downward spiral, with increasing poverty leading to increasing environmental degradation and hence the situation of both the poor and the environment getting worse and worse. The ‘vicious circle’ and ‘downward spiral’ sums up the portrayal of ...