LECTURE 1

What Is Economics?

What is economics? One definition by a well-known economist is that economics is what economists do. This is obviously circular and was meant to illustrate the difficulty of rigidly defining a subject matter that has changed so much over time. A more serious definition is that economics is the study of the allocation of scarce means to satisfy competing ends. Air is not usually scarce, and ordinarily there is no economic problem in the use of air since nothing else must be forfeited. In recent years, however, especially in our urban communities, there has been considerable interest in and concern about air pollution. We can make the air cleaner than it is; for example, Con Edison and the City Government of New York (probably the two major pollutors in New York City) can use more costly methods to reduce their discharge of air pollutants. So clean air is often scarce, and cleaner air can be achieved only by using resources that could be used to satisfy some other end. The ends must be competing in order that value judgments or choices of different kinds are involved. When there are no alternatives, there is no problem of choice and, therefore, no economic problem.

Most important, observe how wide the definition is. It includes the choice of a car, a marriage mate, and a religion; the allocation of resources within a family; and political discussions about how much to spend on education or on fighting a Vietnam war. These all use scarce resources to satisfy competing ends.

In terms of what most economists generally do, however, this definition is too broad. Particularly in Western countries, economists are primarily concerned with the operation of the market sector in an industrialized economy. Yet I will often argue, and this is perhaps the unique theme of these lectures, that the economic principles developed for this sector are relevant to all problems of choice.

For example, economic analysis has been useful in understanding the labor force participation of children and wives, the allocation of time to various nonmarket activities, and family formation. It has also been used with some insight in understanding competition among political parties for elected office. Even illegal behavior and the forces, both monetary and psychic, that determine entry into criminal activities can be usefully analyzed within an economic framework.

Similarly, in recent years economists in Communist countries, such as Russia, Yugoslavia, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia, have discovered that the principles developed by Western economists—involving profits, prices, and interest rates—are of great relevance to their own economies. They often call them by different names, but the concepts are the same. Within our own economy, economic principles are currently being applied with some effect to rather inefficient nonprofit organizations like hospitals and universities.

It is frequently asserted that traditional economic principles are of little relevance in underdeveloped countries having large subsistence sectors and small market sectors. Dean1 has studied the allocation of labor in a poor African country between a subsistence, a cash crop (tobacco), and a hired labor sector. He shows that shifts among these sectors resulting from changes in wages and tobacco prices are similar to those observed in the United States and other developed countries.

Although much of our discussion is also related to the market sector in industrialized economies, the principles being developed are frequently applied to other sectors and different kinds of choices. It is my belief that economic analysis is essential in understanding much of the behavior traditionally studied by sociologists, anthropologists, and other social scientists. This is a true example of economic imperialism! In other words, I argue that the broad definition of economics in terms of scarce means and competing ends should be taken seriously and should be a source of pride rather than embarrassment to economists since it provides insights into a wide variety of problems.

At the same time, our coverage is severely limited in a number of ways. The emphasis is on the allocation of resources under full employment conditions, and little attention is given to fluctuations in the price level, unemployment, or aggregate output. We do not, however, abstract from growth, and we plan to say a fair amount about growth in output, capital, labor, and technology. But fluctuations around trends, including serious fluctuations like the Great Depression, are not covered even though the same basic economic principles are also useful in understanding fluctuations.

In different words, we can say that microeconomics, not macroeconomics, is the subject matter of these lectures. The lectures are most emphatically, however, not confined to microeconomics in the literal sense of microunits like firms or households. Our main interest, as is that of most economists, is in the market behavior of aggregations of firms and households. Although important inferences are drawn about individual firms and households, we try mainly to understand aggregate responses to changes in basic economic parameters like tax rates, tariff schedules, technology, or antitrust provisions.

Another important restriction is that these are primarily lectures on what is called positive economics—the actual, not the desired, behavior of markets and economies. We try to determine, for example, what happens to employment or housing when the government imposes a minimum wage or rent control, without asking very extensively whether these policies should be followed. It is significant that the analysis developed by economists to understand actual behavior has been their major contribution to determining desired behavior, so that indirectly these lectures are also of great relevance to what is called welfare economics.

The Role of Prices

Every society, regardless of its methods of organization, must somehow determine what is produced, how it is produced, and how that product is distributed. The basis of economics is choice, and an economy certainly has many choices among different products, including the choice of how much to set aside for future growth. Choice enters again in determining how to produce, for a variety of techniques and combinations of factors (different kinds of labor, capital, and raw materials) can usually be used to produce the same thing. Finally, there is choice in how to distribute what is produced, that is, choice about the personal distribution of income.

In a complete dictatorship, which even the most centralized economies have never experienced, one person or group makes all these choices. In decentralized market economies like our own, families, governments, and other organizations influence what to produce. They do so not primarily through the ballot box but by the way they spend their resources in the market place. There is a kind of proportional representation in which the influence of each person is not fixed nor shared equally, but is strictly proportional to his command over resources. Influence is exerted by offering to exchange these resources for the goods and services that are desired.

In this process prices play a crucial role even in the nonmarket sector where monetary prices do not exist, for economists have ingeniously discovered “shadow prices” that perform the same function. Because prices are so important, lectures on microeconomic theory can be said to be lectures on price theory. For example, an increase in the demand for product A and a decrease in that for B will bid up the price of A and force down that of B. These price movements encourage resources to enter the industry producing A and leave the industry producing B and thus help accommodate the change in influence.

In addition, prices determine how production is organized. If the price of capital decreased relative to the price of labor, firms would use more capital relative to labor, or if the price of skilled labor decreased relative to that of unskilled labor, they would use relatively more skilled labor. It is quite obvious that prices of factors, together with the personal distribution of the supplies of factors, in turn determine the personal distribution of income. The latter determines the distribution of influence, and the process starts over again.

A central planning bureau could in principle determine what to produce, methods of production, and the distribution of products without relying on prices, but relying instead on input-output tables, resource constraint equations, and the like. Efforts to downgrade prices, however, have led to bottlenecks, unwanted surpluses, and a myriad of problems and complaints. This is why the main thrust of economic reform in Eastern Europe countries has been toward greater reliance on market prices in guiding economic decisions. One of the important goals of these lectures is to demonstrate how market prices influence these decisions.

These lectures cover systematically the various parts of price theory. We begin at one end of the economic system with the demand for final products, and move from there into the rest of the system. A discussion of the supply of final products leads directly into cost conditions. Implicit in the latter is the derived demand for factors of production, which in turn leads into an analysis of production functions. Finally, the supply of factors of production is considered—the supply of labor in general and to particular occupations and the supply of nonhuman capital. This discussion naturally directs our attention to savings, investment, and other forces determining economic growth, that is, to changes over time in the aggregate level of resources.

LECTURE 2

Supply and Demand Analysis

The three basic economic decisions are obviously closely related: what to produce may depend on the distribution of income, just as the latter may depend on what and how it is produced. Thus it has been said that in economics everything depends upon everything else. Critics have even accused economists of circular reasoning when describing the operation of the interdependent pricing mechanism.

The French economist Walras analyzed this problem of interdependence and showed that there is no circular reasoning, just mutual determination or general equilibrium. Anyone who has studied high school algebra knows that each of the unknowns in a system of simultaneous equations can be determined1 provided a sufficient number of independent relations are available. Walras similarly demonstrated that all prices and quantities in the economic system can be simultaneously determined because there are a sufficient number of independent supply and demand equations. Walras’ demonstration was a major achievement with far-reaching implications, perhaps the greatest achievement of nineteenth-century economics—simple as it appears to a modern student.

The problem facing someone trying to learn about the economic world is: Given its apparent complexity and interdependency, how can it be made amenable to analysis? One approach is to say: “The world is complex, there is no escape from this. Realistically, it must be recognized that the demand for, say, butter, depends not only on the price of butter but also on the prices of margarine, lard, apples, beef, automobiles, machinists, economists; you name it, it is relevant.” This approach takes the Walrasian equations and their interdependencies seriously and makes no attempt to reduce them to a simpler form.

A second approach, more pragmatic and in the English tradition, argues that to solve practical problems one must find a way to break into Walras’ complex system. The analyst must be able to concentrate on the few variables he considers important for a particular problem and neglect the variables he considers unimportant. In the economist’s own language, he must allocate the limited resources available to him for a particular study in the most efficient manner, which means considering just enough variables to obtain sufficiently accurate answers.

To continue with the butter illustration, the more pragmatic economist would want to consider the price of butter and probably the level of income, the price of margarine, and the size of the population as well. But he would neglect thousands and thousands of other variables that in principle might have an influence—the prices of beef, labor, and capital, tariff policies, and so on. The variables considered would not always remain the same. A law that prevents the artificial coloring of margarine could be quite important because it would reduce the demand for margarine and increase the demand for butter. Although the variables considered are not rigidly fixed, they are always a small fraction of the number entering Walras’ system.

The major tool that has been invented to simplify the economic world is supply and demand analysis, brought to its highest development by Alfred Marshall. Supply and demand are the “engines of analysis” that enable an investigator to discuss systematically the variables he considers pertinent for a particular problem. They enable him to use his limited resources efficiently to obtain sufficiently accurate answers. Although often called partial-equilibrium analysis, a more accurate name for the supply-demand approach would be “practical general equilibrium analysis.”

On one level, supply and demand analysis is simply a language or classification scheme: How does variable X affect the demand function, variable Y the supply function, and variable Z both? The classification of animals has been a useful language in zoology, and many other languages have been extremely useful in other scientific fields. The language of supply and demand has been especially fruitful in solving economic problems because of the assumption that many variables affect either demand functions or supply functions, but not both. This assumption is no longer simply part of a language, but is a strong condition imposed on behavior. Its great empirical significance is that it permits one to reach conclusions about the effects of various changes on prices and outputs with relatively little information.

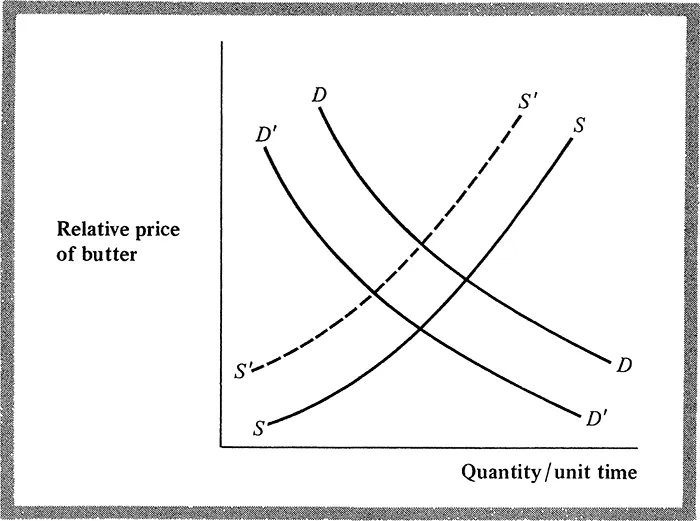

Suppose, for example, the price of margarine declined because an excise tax was removed. This would shift the supply curve of margarine to the right, lowering its price and thereby inducing the public to substitute margarine for butter, which would shift the demand curve for butter to the left. But it would have a negligible impact on the supply curve since butter and margarine are produced with very different resources, although soybean fields can make good cow feed. The hypothesis that the demand curve and not the supply curve for butter is altered by a change in the price of margarine, along with some other assumptions, permits a simple analysis of the responses in the butter market. In Figure 2.1, DD and SS are the initial supply and demand curves for butter drawn on the assumption that the price of margarine is fixed, and the initial market equilibrium is given by their intersection. Removal of the tax reduces the price of margarine and thus reduces the demand for butter at any given butter price, but does not change supply conditions. The leftward shift of the demand curve to D’D’ reduces both the price and quantity of butter.

To reach these important qualitative conclusions, we assumed (1) the direction of shift in the demand curve, (2) no shift in the supply curve, and (3) the signs of the...