![]()

CHAPTER 1

The Business Case for a Sustainable Supply Chain

BEFORE STARTING WORK ON BUILDING a sustainable supply chain, it is vital that you understand the business case for doing so as it applies to your business. A chemical company faces quite different drivers for sustainability than, say, a public transport provider, as they have different supply chains, different customers and come under different legislation. Those different drivers will shape quite different supply chain strategies.

In generic terms, the drivers affecting business are:

- legislation and standards;

- cost pressures;

- availability of materials/continuity of supply;

- environmental risk reduction;

- reputational damage;

- customer demand;

- the moral imperative.

Legislation and standards

Years ago, I was at an eco-design conference and got into a conversation with a researcher from an American electronics brand. She was presenting how her company was meeting the EU’s then forthcoming Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE) and Restrictions on Hazardous Substances (RoHS) directives. ‘Why would a US company care about EU legislation?’ I asked naively. ‘Because Europe is a huge market,’ she answered, ‘and we want to be in it.’ This exchange brought it home to me that, in a globalised world, legislation can have impacts far beyond its geographical scope as it travels down the supply chain.

Environmentally damaging substances are always at risk from legislation. The Montreal Protocol led to the phasing out of many ozone-depleting substances; the International Maritime Organisation has banned the use of tributyltin-based boat anti-foulings; and the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants is phasing out or restricting a significant number of pesticides, flame retardants and other chemicals. If such chemicals feature in your supply chain, then the risk of them disappearing must be factored into your forward plans.

Legislation impacts can be wider than just bans, but can include mandatory disclosures. The new UK Government requirement on FTSE companies on carbon reporting is initially restricted to emissions from fossil fuels,2 emissions from processes and those associated with electricity used on-site (Scope 1 and 2 in the jargon – see Chapter 2). The government has made it clear that it expects that supply chain emissions (Scope 3) will be included in the future.

At the time of writing, the most popular environmental management standard, ISO 14001, is under revision and, when the new version is published in 2015, it is expected to take a lifecycle perspective rather than its current organisational focus. This means that organisations will need to cover issues arising in the supply chain if they wish to retain certification.

Cost pressures

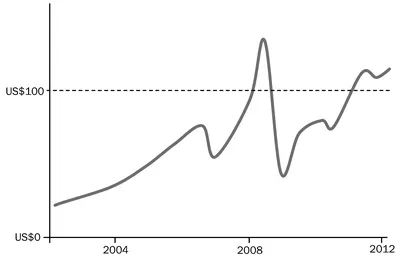

FIGURE 1. Brent oil prices.3

It is common for energy prices to surge ahead of a major recession, but just before the 2007/08 recession they hit record levels (Figure 1). Usually the price will fall again after a crunch, but in 2009 oil prices bounced back and have stayed high since, despite ongoing financial problems in major markets and the shale gas boom in the US. This suggests that the days of cheap oil, upon which the modern economy was built, are over. This impacts not only on road fuel, but also on oil-based polymers, food and many other goods and has been blamed for continuing economic stagnation in major economies.4

FIGURE 2. MGI Commodity Index.5

It’s not just oil either as you can see from the commodity price index shown in Figure 2. Having spent the twentieth century falling, commodity prices as a whole have bounced back to record levels. It is no surprise then that nearly a third of profit warnings by FTSE 350 companies in 2011 were attributed to rising resource prices.6

Availability of resources/security of supply

Rising costs may be the symptom of under-pressure resources, but the ultimate risk is vital materials becoming unavailable. The term ‘peak oil’ was coined by Hubbert King in the 1950s to describe the situation where supply couldn’t keep up with demand (not ‘oil running out’ as it is often misrepresented). Fatih Birol, Chief Economist at the International Energy Agency, believes we are now in, or close to, the ‘peak zone’.7 As well as oil, ‘peak’ has been applied to all sorts of important resources from fish to uranium.

The supply of rare earth materials, essential to many modern electronic gadgets, is of particular concern. It is rumoured that one of the reasons why so many electronic companies have outsourced their production to China is not just to exploit cheap labour but also to ensure access to vital rare earth metals of which China has a fiercely guarded near monopoly (97% of supply8).

A recent survey by the manufacturers’ organisation EEF found 80% of senior manufacturing executives thought limited access to raw materials was already a business risk. For one in three it was their top risk.9 As well as physical availability of materials there is also the risk that, say, a particular chemical critical to your operations is either banned or withdrawn voluntarily on environmental grounds. ‘Security of supply is part of the business case for us’, says Sean Axon of precious metal and catalyst giant Johnson Matthey plc. ‘Anticipating and planning for changes in the supply of materials has an impact on the products we make and their formulation.’ Despite being in a very different industry, Stephen Weldon of high street bakers Greggs concurs: ‘Security of supply is a big issue when we come to negotiate contracts.’

Environmental risk reduction

If you phase out the purchasing of toxic materials, then you won’t have to store them on site, which reduces the risk of a major pollution accident. It also contributes to occupational health objectives by reducing the risk to employees at source.

Likewise if you phase out the use of toxic materials in your product, it reduces the risk of, say, being prosecuted for the impacts of that substance. In both these cases, risks are eliminated if the substances never cross into the company premises in the first place.

Reputational damage

In the Introduction, we discussed how Apple was targeted by Greenpeace in 2005. This was not the end of their woes. In 2011, the Beijing-based Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs claimed Apple’s Chinese suppliers frequently fail to properly dispose of hazardous waste. ‘Apple has made this commitment that it’s a green company,’ said Ma Jun, the director of the Institute. ‘So how do you fulfil your commitment if you don’t consider you have responsibility in your suppliers’ pollution?’ 10

Note that the NGO does not attack, or even name, the suppliers themselves, or indeed the multitude of other Western brands that use the same suppliers. They pick Apple because its high profile means they will get the headline. This is known as ‘tall poppy’ syndrome – that the highest profile brand will get targeted because they stand out, and it means it is the biggest names that will be held responsible for the sins of their suppliers. So building a sustainable supply chain is an essential element of brand protection.

As we discussed before, BP and Tesco have also suffered serious reputational damage recently as a result of the actions of their suppliers – in the Gulf of Mexico oil spill and the ‘horse-burger’ scandal, respectively.

Customer demand

In the same way that reputational damage moves up the value chain to your organisation, it can also flow through to your customers. It is becoming increasingly common that customers are demanding that firsttier suppliers take responsibility for lower tier suppliers. ‘Some of the surveys and questionnaires we receive from customers almost take it as read that the company is doing everything we should within its own operational boundary’, says Johnson Matthey’s Sean Axon. ‘They are now much more interested in our management of our suppliers.’

There is also the risk that a rival or newcomer will make your product/service redundant by replacing it with a more sustainable equivalent. For example, the rise of biodiesel production means that most glycerol in the UK now comes from biodiesel by-products, dominating the market over traditional fossil fuel sources.11 Or as Ramon Arratia of flooring company InterfaceFLOR put it, ‘we are doing less business with the companies that were not able to support our goal of 100% recycled or bio-based raw materials’.

Customer demand provides a business opportunity too. Major retailers like Marks & Spencer are increasingly positioning themselves as ‘gate-keepers’ for consumers, removing the need for the general public to understand the sustainability impact of the products they buy. De-risking supply chains can be a business opportunity for business-to-business (B2B) businesses too.

Moral imperative

Throughout history, there have always been companies with a strong sense of moral purpose. Famous examples include Henry Ford’s desire to democratise transport, or Cadbury’s desire to provide working people with drinking chocolate as an alternative to alcohol. Modern equivalents such as Body Shop and Whole Food Markets see a moral imperative in enhancing society and the environment. These organisations say they do not exist to make profit, but rather they make profit in order to carry out their higher purpose.

The moral imperative viewpoint often makes decision-making more straightforward. ‘Be...