- 248 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

An Introduction to Child Language Development

About this book

This volume introduces the field of child language development studies, and presents hypotheses in an accessible, largely non-technical language, aiming to demonstrate the relationship between these hypotheses and interpretations of data. It makes the assumption that having a theory of language development is as important as having reliable data about what children say and understand, and it advocates a combination of both `rationalist' and more 'empiricist' traditions. In fact, the author overtly argues that different traditions provide different pieces of the picture, and that taking any single approach is unlikely to lead to productive understanding.

Susan Foster-Cohen explores a range of issues, including the nature of prelinguistic communication and its possible relationship to linguistic development; early stages of language development and how they can be viewed in the light of later developments; the nature and role of children's experience with the language(s) around them; variations in language development due to both pathological and non-pathological differences between children, and (in the latter case) between the languages they learn; later oral language development; and literacy. The approach is distinctly psycholinguistic and linguistic rather than sociolinguistic, although there is significant treatment of issues which intersect with more sociolinguistic concerns (e.g. literacy, language play, and bilingualism). There are exercises and discussion questions throughout, designed to reinforce the ideas being presented, as well as to offer the student the opportunity to think beyond the text to ideas at the cutting edge of research.

The accessible presentation of key issues will appeal to the intended undergraduate readership, and will be of interest to those taking courses in language development, linguistics, developmental psychology, educational linguistics, and speech pathology. The book will also serve as a useful introduction to students wishing to pursue post-graduate courses which deal with child language development.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

What do children bring to the language acquisition task?

Chapter summary

In this chapter, the issue of whether children bring innate knowledge of linguistic principles to the language acquisition task is raised in broad, mostly philosophical, terms. The issue of how one can know what children know (innate or not) is discussed. Two approaches to language acquisition research are identified — the 'observational' and the 'logical' — and examples of each are given.

Introduction

Perhaps the most hotly debated topic in child language research today concerns how children's mental and physical capabilities help them learn languages, and what they know in those months and years before their talk is recognisable. There are those who believe that children 'know' a great deal about language — much more than might at first appear from what they say (or are able to say). There are others, however, who believe that children know very little about language, and must work it all out from hearing (or seeing, in the case of sign languages) the language of others and from their own attempts to use language.

The reason why we can't decide what infants know or don't know is that we cannot observe knowledge directly. We can't get inside children's heads, but have to use more or less subtle methods of observation and experimentation that we hope will give us the clues we need. However, children's behaviour, even in response to the most controlled experiment, is often ambiguous and could be interpreted in more than one way. And they certainly can't sit down and tell us any of what they know, until they are at least three or so. In fact, even then, they can only tell us what is available to conscious reflection. Most of what anyone, child or adult, 'knows' about language is not directly accessible, and must be probed in ways only slightly more direct than with small children. (A detailed discussion of how children learn to talk about language is contained in Chapter 8.) How can we know what children know about language?

A challenge to ingenuity

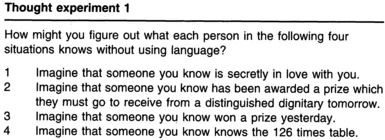

Trying to determine what someone knows when they are unable to tell you takes plenty of ingenuity.

In the first case, unless the love is to remain unrequited, eventually the person will show by some look, touch, or conventional action (such as sending flowers) that they love you. In the second case, patience is called for. You will discover they have been awarded a prize if you wait around long enough to see them get dressed up and go to meet the dignitary, who then gives them the prize. You will know that the person already knew they had won a prize from the fact that they dressed up specially to meet the dignitary, although perhaps meeting the dignitary was known, but receiving the prize was a surprise. If the latter is the case, then you would expect some betrayal of surprise when the prize is given; perhaps a gasp of 'Ooh' accompanied by raised eyebrows.

in the third case, you have a greater problem. Something has happened in the past. You might be able to figure out that the prize had been awarded by the presence of the prize on a shelf, or perhaps by the respectful way others treat your friend. But you have missed the opportunity to observe the event directly. In the fourth case, you have an almost insurmountable problem. It is conceivable that a situation may arise that calls for the instant multiplication of 126 by some number, and that your friend provides the number either by saying it, or, if language is not to be used at all, by counting the product of the multiplication in matchsticks or some such.

Each of these situations mirrors part of the problem of determining what young children know about language (or about anything else, for that matter). Some things they are able to 'betray' directly by their actions. Children betray directly that they are hungry, dirty or tired, for example, by crying (although it remains to be seen whether these are distinguishable from each other on the basis of the cry alone). Children can also betray an understanding of language by doing what is asked of them, by looking at objects named by someone else, or picking them up, for example. These indicators are, however, pretty minimal given the complexity of language, and it is often not clear with very small children that they have responded to the language rather than to gestures or other clues to what a speaker meant. We can also observe children's beginning attempts at speech; but that too is limited by the fact that they may 'know' far more than they can say. In fact, language comprehension studies with small children indicate that children do indeed understand a great deal more than they can say, and thus observations of child speech (language production) may be woefully inadequate as a way of determining what they know about language. However, we must do the best we can with what we've got. As the thought experiment is intended to suggest, just because we cannot observe something someone knows even indirectly, does not mean that that person doesn't know it. You may know (consciously) many things you have never told a soul; an infant may know (unconsciously) many things it cannot tell a soul. And if we are interested in that knowledge, we will just have to get more ingenious at deducing it by indirect methods.

In some cases, we can figure out what infants know by waiting around for them to produce utterances, either as initiating contributions to conversations or as responses to other people's utterances, that can plausibly be said to indicate knowledge of specific kinds. For example, when children say things like 'no water' when they are offered a cupful, we may presume they know what words are (unconsciously, of course), that words can be combined, that words carry meaning, that words in combination carry a meaning that is in some way a combination of the meanings of the individual words (i.e. that 'no' and 'water' each carry a meaning singly and in combination), that directing words to other human beings is a sensible thing to do, and that it is likely to have some effect. We might also presume that some of this knowledge may have been learned through experience with language; other linguistic knowledge may be innate (built in as part of the genetic code of human beings). Knowing that communicating with others is a sensible thing to do, for example, is a particularly likely candidate for innate knowledge. Knowing that words are the building blocks of communication may also be a candidate for innate knowledge. Knowing that 'no' means 'no' and 'water' means 'water' is a highly unlikely candidate for innate knowledge. Children learn what the individual words of specific languages mean by observing those around them, otherwise we would have to assume that all children are born knowing the meanings and forms of all the words in all the world's languages — a patently absurd conclusion (although they do seem to be born with some preconceptions about words — that they can refer to objects and activities, for example). Thus it seems clear that some parts of language are candidates for innate knowledge, and some must certainly be learned from input (the language children hear around them). The trick to language acquisition study is trying to figure out which type of knowledge belongs to which category.

Two different approaches

Researchers differ on the extent to Which they are willing to credit children with innate knowledge of language. The differences result in (or are indicative of) two rather different approaches to language acquisition in general. Let's look briefly at these two approaches.

The observational approach

If one presumes young children know nothing innately, then one could decide to credit them with specific knowledge of language only when there is some substantial direct evidence for doing so. For example, let's say you've been observing young children aged about two, and you've noticed that they keep producing utterances without subjects. That means that instead of saying, 'I/me want cookie', they routinely say, 'want cookie'. Instead of saying 'Mummy do it', they say 'do it'. What I am calling the 'observational approach' would lead you to say that these children do not know what subjects are or how to use them. (As we will see in the section below, the 'logical' approach leads to a very different conclusion.) The observational approach is a very sensible approach to take. It prevents one from making wild claims about what children know in the absence of fairly direct evidence. It leads to the assumption that if children produce utterances with certain features (say, having subjects, or showing subject—verb agreement marking, as in 'He wants cookie' (rather than 'He want cookie')), then they must have learned those features from listening to the language that is spoken to them or around them, analysing it in some way (and there's the rub, but more of that anon), and then reproducing it in their own speech.

However, there are those for whom the account of language acquisition I've just summarised just doesn't work. Their observations lead them to conclude that children know much more than they could have figured out from observing the language of others. These researchers bring a particular kind of logical deduction argument to their analysis of what they see. They pursue what I will call here a 'logical approach'. However, please note that by calling this second approach 'logical', I am not at all implying that the observational approach is somehow illogical. The term 'logical' in this context simply means that making a logical deduction is at the heart of the second approach.

The logical approach

In the logical approach', children are hypothesised to know innately whatever they could not have learned from observing and analysing the language they hear. Researchers in this second camp believe that there must be a great deal that children know about language from birth because they produce and understand utterances with features they could not possibly have deduced from the input. Examples of this claim get a bit complicated because they depend on a pretty sophisticated understanding of the structure of adult language, but let me try a fairly simple example.

Look at the four sentences below:

- (1) *Who do you think that knows Mary?

- (2) Who do you think knows Mary?

- (3) Who do you think that Mary knows?

- (4) Who do you think Mary knows?

Sentence (1) has a star by it because it is generally judged by speakers of English to be ungrammatical, i.e. could not have been produced by the speaker's linguistic system functioning normally. Please note, however, that many of the utterances that are judged ungrammatical by prescriptive grammarians such as school teachers and other guardians of 'proper' English (such as 'I ain't got none') are not regarded as ungrammatical by linguists (just socially 'non-standard'). Linguists, therefore, are interested in the difference between grammatical and ungrammatical utterances viewed descriptively in terms of what people actually say (rather than presciiptively, in terms of what they ought to say), and a by a sentence or utterance is the conventional way linguists denote descriptive ungrammaticality.

Returning to the sentences above, while the first is impossible, the other three are perfectly grammatical. In other words, in sentences where the structure leads to the interpretation that someone knows Mary, the 'that' cannot appear before 'knows'. In sentences where the structure means that Mary knows someone, the 'that' can appear. In structural terms, we can say that if the missing 'someone' in these sentences is the subject of the embedded clause, the 'that' may not appear. If the missing 'someone' is the object of the embedded clause, the 'that' is free to appear or not, as the speaker chooses. Below are the same four sentences with the missing someone represented by an [e] (= empty). I have also indicated the boundaries of the embedded clauses with square brackets:

- (1') *Who do you think that [e knows Mary]?

- (2') Who do you think [e knows Mary]?

- (3') Who do you think that [Mary knows e]?

- (4') Who do you think [Mary knows e]?

OK, so what does all this have to do with children's language development? Well, presumably, children's language development eventually results in adult language knowledge of these (and myriad other) facts. And notice that this knowledge is unconscious even in adults, unless they have had it pointed out to them, or have engaged in direct linguistic analysis themselves. (Did you know this about your language before I told you?)

Thus, somehow, children know or come to know that sentences such as (1) are not part of the English language. However, apparently no one teaches them that fact. They do not, for example, hear people saying such sentences, and then correcting themselves to produce the legitimate one (2). Or, at least, if people do that, we haven't observed it yet. It certainly would not seem to be a major part of language experience for the young child. It is more likely, say those in the 'logical approach' camp, that this knowledge is somehow innately specified in a very general (and abstract) form. It is general in that the feature being exemplified here doesn't apply only to simple English sentences such as those shown in the examples, but, properly described, is a very general feature of human languages. It is abstract because in order to show up in all the world's languages, it cannot be represented in the child's mind initially in terms of involving the word 'that' because that is a word of English only, so the rule itself must be more abstract, i.e. not specific to English.

So, the 'logical approach' argument is as follows:

- Here is an odd and rather difficult to describe feature of the English language.

- We have no evidence that it is taught to children; and we have no evidence that the particular pattern of appearances and non-appearances of 'that' in such sentences is deduced from observation.

- If adults know it (unconsciously), and children don't learn it, then it must have been known innately.

- Obviously, children are not going to know innately that these particular English sentences pattern this way, so there must be an innate formulation of this pattern that can apply to all languages. That this might be the correct view is bolstered by the fact that many other languages, perhaps all, reflect the same type of patterning, thus lending credence to the view that this is innately known knowledge.

Clearly this is a rather more complicated approach than the observational one, but it leads to some very interesting claims. The argument I've just summarised, for example, can lead to the prediction that children learning English will never naturally produce sentences such as those in (1). This can be tested, perhaps by trying to get children to repeat sentences such as these, and seeing how resistant they are to saying such things.

Logical arguments about language acquisition also clearly depend on some crucial assumptions about what can and cannot be learned from experience, and it is actually very hard to say what children do not learn from experience, since no one has been able to follow even a single child around long enough to be able to document everything the child hears and every attempted utterance he or she produces. The absence of this kind of complete record is one of the reasons the debates between the 'observational' and the 'logical' approaches remain so active and energetic. Those in the 'logical' camp think it is a waste of time to go looking for such an extensive record because all the input (i.e. language exposure) in the world won't be enough to 'teach' language. Those in the 'observational' camp are persuaded that since so much has been discovered about children's language experience, the 'logical' group are slamming the doors shut on explanations without having given more sophisticated observational and experimental techniques time to contribute to the debate. They accuse the 'logical' folks of sitting idly cogitating in their armchairs, while they are doing the work of running around the world collecting data in time-consuming and even dangerous situations. Meanwhile, the 'logical' folks think the 'observationalists' are wasting time and money chasing around after something they will never find. Of course, if observationalists didn't go on getting grants to run around the world collecting data from children learning Samoan, or Sesotho, or whatever, the 'logical' folks wouldn't be able to test their hypotheses, nor would they have challenging language acquisition data to keep the fires of cogitation going. No wonder child language research can be so contentious. Anyway, let's put the politics on one side for a moment.

To return to the 'logical approach': in this approach children are assumed to know many things about language before they even begin to ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface: How to use this book

- Acknowledgements

- 1 What do children bring to the language acquisition task?

- 2 How do children communicate before they can use language?

- 3 When does language development start?

- 4 How do young children think language works?

- 5 What influences language development?

- 6 Do all children learn language the same way?

- 7 Does it matter which language(s) you learn?

- 8 When does language development stop?

- Appendix 1 Tools for studying children's language

- Appendix 2 Phonetic symbols

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access An Introduction to Child Language Development by Susan H.Foster- Cohen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.