![]()

1

Introduction

___________________________

Mankind’s increasing powers

In the past decades, systematic concepts and theories on justice between non-overlapping generations have been developed for the first time ever – 2600 years after the first theories on justice between contemporaries had been articulated. This delay can be explained by the different impact of mankind’s scope of action, then and now.

In his epoch-making book The Imperative of Responsibility (first published in German in 1979), the philosopher Hans Jonas points to the fact that the potential to irreversibly impair the future fate of mankind and nature by actions and omissions is increased by modern technology. Jonas clearly works out what held true throughout all ages up to the 20th century:

With all his boundless resourcefulness, man is still small by the measure of the elements, precisely this makes his sallies into them so daring... Making free with the denizes of land and sea and air, he yet leaves the encompassing nature of those elements unchanged, and their generative powers undiminished... Much as he harries Earth, the greatest of Gods, year after year with his plough – she is ageless and unwearied; her enduring patience he must and can trust, and to her cycle he must conform. (Jonas, 1980, p25)

Jonas can be criticized for considering nature stable and indestructible. Such a concept is surely one-sided and is no longer advocated by ecologists in such general terms. In view of the five geological phases of global extinction of animal species (Cincotta and Engelmann, 2001, p31) and the cycles of ice and warm ages, nature must be seen as far more vulnerable to catastrophes.

However, Jonas’ decisive and indisputable point is that, throughout history, man had relatively little influence on global, supra-regional nature before the modern age. Man was not able to throw the ecosystem he lived in off balance. He did not adapt to nature on grounds of reason, but simply because he had no choice. Under these circumstances, there was no need for an ethics of responsibility to nature. Rather, man was well advised to approach nature with as much cleverness and efficiency as possible to sufficiently benefit from its seemingly boundless resources.

But, things he had to accept as his fate in earlier times gradually came within his scope of influence in 20th century. The long-term effects of nuclear energy were not conceivable in the past, except in utopias with a science-fiction character. The same applies to the magnitude of climatic changes – which are, after all, an influence on the basic biophysical conditions of our planet itself.

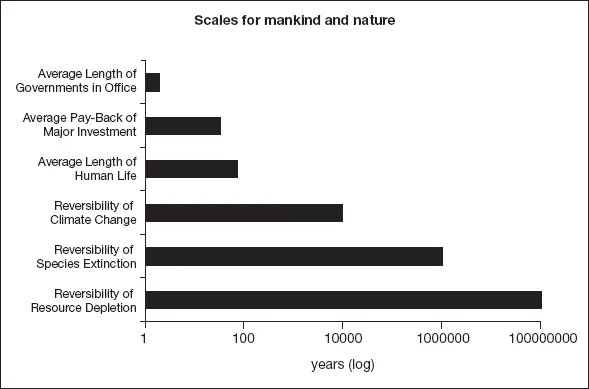

As the comparison of standards of mankind and nature in Figure 1.1 shows, we are able now to shape the future by intervening in the household of nature to a great extent, for millions of years.

Source: Tremmel (2006b, p188)

Figure 1.1 Relevant timescales for mankind and the environment

Let us take nuclear waste as an example. A country like Germany (which is not a nuclear power and thus does not reuse plutonium for military purposes) has produced in its nuclear power plants 118 tonnes of plutonium (Pu-239) as a waste substance until now.1 Plutonium has a half-life period of 24,110 years. So, according to our present state of knowledge, 1 gram (g) of our present waste plutonium will still be left in 310,608 years, and 1g can be lethal for a human being.2

If we consider that our written history is only 10,000 years old, the permanence of the burden present generations are placing on the shoulders of future generations becomes quite clear. The Berlin semiotician Roland Posner explains:

In all three fields [nuclear, genetic and space engineering; annotation J. T.], we are dealing with time spans that go beyond that of human history up to now. The science, literature, and art of earlier centuries become unintelligible if they are not re-interpreted and translated into new languages every few generations. In the same way, state institutions have rarely existed for more than a few centuries, and they are constantly threatened by war and subversive movements. Even present-day religions are not much older than a few thousand years, and they have not primarily handed down scientific information to us, but myths and rituals. (Posner, 1990a, p8)3

The man-made climatic change, the depletion of the oceans through unsustainable fishing, the clearing of the wilderness for plantations and the loss of biodiversity are by no means new phenomena. But in earlier times, they were limited to certain areas, whereas they are now taking place on a global scale and at a far greater pace (Knaus and Renn, 1998, pp37–43).

The enormous increase in mankind’s powers that has taken place in the 20th century explains why even the most important moral philosophers of the past hardly paid any attention to our responsibility towards posterity. Kant, for instance, writes the following:

What remains disconcerting about all this is, firstly, that earlier generations seem to perform their laborious tasks only for the sake of later ones, so as to prepare for them a further stage from which they can raise still higher the structure intended by nature; and, secondly, that only later generations will in fact have the good fortune to inhabit the building on which a whole series of their forefathers (admittedly, without any conscious intention) had worked, without themselves having been able to share in the happiness they were preparing. (Kant, 1949, p6 et seq.)

According to Jonas, the universe of traditional ethics is limited to contemporaries, that is, to their expected lifspan. This ‘neighbour ethics’ is not sufficient anymore. ‘The new territory man has conquered by high technology is still no-man’s-land for ethical theory’, he writes (Jonas, 1979, p7).

If Jonas is correct, moral philosophy still lives in the Newtonian age.

The no-man’s-land of ethics

This convincing plea for a fundamental and radical extension of the scope of ethics is in stark contrast to the opinion of many moral philosophers who believe that all important moral principles have essentially already been brought forth and discussed in the long history of ethics, so there can be no fundamental changes. Here, for example, is Robert Spaemann’s witticism: ‘In questions of how to live life rightly, only wrong ideas can truly be new’ (Spaemann, 1989, p9). For millennia, ethics have dealt with future generations with the confidence that the future is likely to resemble the past. Therefore, the idea of generational justice4 might be a discontinuity in the history of ethics. Vittorio Hösle points out:

that a certain model of justification of moral standards, namely that of a reciprocal consideration of interests for egoistic reasons, has been impeached by the idea of the rights of future generations...: those living in one hundred can hardly impose sanctions on us for the harm we are doing to them today. Now, to believe our moral obligations are a function of our own selfish interests is by no means the only existing approach to a justification of morals in modernity, but since Hobbes it has been a particularly popular one that has greatly influenced the leading social sciences economics and political science. Therefore, it can be said that one line of modern ethics – a decisive one – is being challenged and probably even impeached by the idea of generational justice. (Hösle, 2003, p132 et seq.)5

Rawls – much like Kant a few hundred years before him – takes an ‘autonomous social savings rate’ (Rawls, 1971, pp319–335) for granted, a type of natural law by which the living conditions of future generations will continuously improve. But the image of the ‘spoilt heir’ has now been replaced by the concern that future generations might become the ecological, economic and social victims of the short-sighted politics of today’s generations. That extends the range of responsibility of those living today. Under our present circumstances, responsibility for future generations, which is more or less included in the traditional concept of responsibility, must be interpreted in a completely new light (Birnbacher, 2006a, p23).

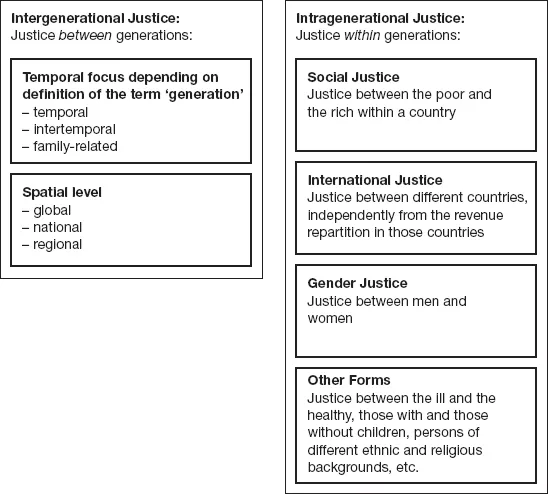

However, such ‘remote ethics’ often meet with numerous objections, which are discussed later on. First of all, the difference between inter- and intragenerational ethics requires clarification. Depending on the definition of the term ‘generation’, generational justice is conceivable as justice between the present and future generations (intertemporal generations), also as justice between the young and the old (temporal generations) and between family generations. But basically, intergenerational justice is not conceivable between persons of the same age. Questions of justice between persons of the same age – be they of a different social standing, sex, race, sexual orientation or nationality – are matters of intragenerational justice (see Figure 1.2).

Ethics of the future – in a double sense

The concept of generational justice is likely to play a greater role in future philosophy. Ever more social actors are demanding new ethics of future responsibility. Ever since the beginning of the global ecology movement, the interests of future generations have been advanced as an argument. Avner de-Shalit even claims: ‘In fact, the most important element in the question of intergenerational justice is the environmental issue, to which almost every aspect of intergenerational justice is related’ (De-Shalit, 1995, p7). If, however, the shifting of ecological burdens to the future is an ethical problem, so is the shifting of burdens in other areas. Therefore, such ethics would necessarily have to include not only ecology but also other political fields. Already by the 19th century, Thomas Jefferson called national debts a problem of intergenerational ethics.6 Comprehensive generational accounting methods are now being developed to determine the burdens on future generations (Auerbach at al, 1999). A fresh impetus has been given to the debate on generational justice in the more developed countries (MDCs)7 by the demographic development in the last quarter of the 20th century, which has prompted forecasts of a ‘turn toward less’. Numerous representative studies prove the widespread fear of, particularly younger, people that they will not be better but worse off than their parents. In the US, the term ‘boomerang generation’ has come into use; the German version is ‘Generation Praktikum’, and the French version is the ‘génération précarité’.

Figure 1.2 Spheres of intergenerational and intragenerational justice

In the medium term, the question of justice between the young and the old or between present and future generations might become as important in philosophy as the question of social justice, i.e. justice between the poor and the rich. But, as yet, it is still being worked out. In 1980, Ernest Partridge, one of the first editors of an anthology on responsibility for the future, criticizes:

The lack of manifest philosophical interest in the topic is further indicated by the fact that of the almost 700,000 doctoral dissertations on file at University Microfilms in Ann Arbor, Michigan, only one has in its title either the words ‘posterity’, ‘future generations’ or ‘unborn generations. (Partridge, 1980a, p10)

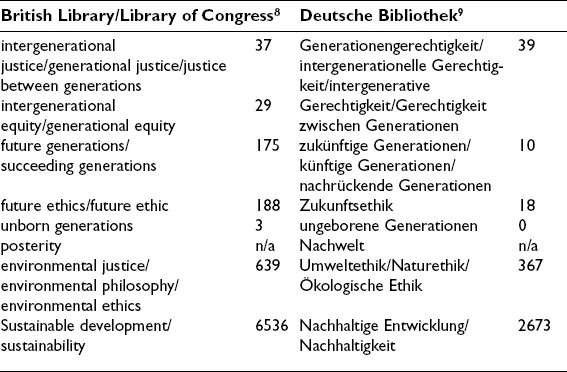

Here, a lot has changed. Taking into account the new publications in English and German over the past decades, the list has grown quite long, as Table 1.1 shows.

Table 1.1 Number of publications on generational justice in the widest sense

A few notes on the results are:

• ‘Intergenerational justice’/‘generational justice’/‘justice between generations’ is only included in 37 titles or subtitles.10 Many of the most important English publications were already written in the 1980s. There are 39 German publications with the term ‘Generationengerechtigkeit’ included in their title or subtitle. Many of them were written after 1990.

• The hits for ‘intergenerational equity’/‘generational equity’ mainly refer to philosophical or economic texts on discounting and to economic texts on pension schemes and national debts. These results partly overlap with ‘generational accounting’, a special procedure for balancing national debts that is now used in many countries.

• The number of hits for the term ‘future generations’ was originally far higher but many of them had a different context and were excluded. Many of the remaining publications concerned future studies, forecasts or projections and hopes that certain material things or contents of consciousness will be preserved for future generations. The remaining hits also include numerous audio documents. The number of publications in the field of political philosophy is rather low.

• Many hits were found for the term ‘posterity’, used by Partridge, but they belong to other contexts. It is not a very useful search word for finding literature on just relations between generations. That also applies to the German translation ‘Nachwelt’.

• Of course, questions of generational justice might also be dea...