![]()

1

Overview of embedding corporate sustainability

David Grayson

Professor of Corporate Responsibility

An influential survey of Chief Executive Officers conducted by Accenture for the UN Global Compact (UNGC) in 2010 found that 96% of CEOs from around the world believe that sustainability should be fully embedded into the strategy and operations of a company.8

The survey was specifically among CEOs of companies that have signed up to the Global Compact. In a sense, therefore, one might ask, what were the other 4% doing as CEOs of Compact companies! While clearly not representative of business as a whole, the Accenture survey (to be repeated in 2013) is indicative of greater recognition among business leaders (and not just those who are regular attendees at the annual Davos World Economic Forum) that managing a company’s environmental, social and economic impacts is now business critical.

The reasons for this are now well rehearsed:9 a global population already over 7 billion with expectations of 9–9.5 billion by midcentury; an increasing middle class, with predictions of 100–150 million10 more people joining the world’s middle class every year between now and 2030, with increasing demands for stuff. This will require 50% more energy, 50% more food and 30% more water supply by 2030—all to be generated while the world tackles the challenge of climate change.11

Hardly surprising, therefore, that other recent surveys reinforce the conclusions of the Accenture study. Just over 60% of companies surveyed by KPMG in 2011, for example, said that they currently have a working strategy for corporate sustainability—up from just over half polled in a similar survey in 2008; and nearly 50% of all executives surveyed believed that implementing sustainability programmes will contribute to the bottom line, either by cost reduction or increased profitability.12

Even the Accenture study, however, found a performance gap between what CEOs themselves said was necessary to embed sustainability and what they thought their own companies were yet doing.13 Allowing for some CEO rose-tinted spectacles, there remains a major challenge to convert intent into reality.

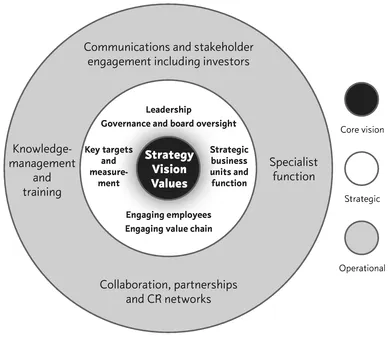

At the Doughty Centre, we have been refining a model for embedding sustainability, which emerged from the Academy of Business in Society (EABIS) Colloquium hosted at Cranfield in 2008. It was first proposed by then Cranfield doctoral student, David Ferguson, based on his PhD thesis looking at embedding in EDF Energy. Our model encompasses all the elements cited in the Accenture/UNGC survey: board oversight; embedded in strategy and operations of subsidiaries; embedded in global supply chains; participation in collaborations and multi-stakeholder partnerships; and engagement with stakeholders such as investors.14 However, we also explicitly incorporate the importance of leadership (‘top-down’) and employee engagement (‘bottom-up’). We also include more operational enablers such as knowledge management and training for sustainability; engaging more stakeholders than just investors (important though it is to explain better to investors how sustainable development changes the strategy of business); and the role of the specialist corporate responsibility (CR)/sustainability function (see Fig. 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Embedding sustainability

Internally, we call this the ‘bull’s-eye’ model after the popular game of darts where, ultimately, the winner has to score a bull’s-eye—the centre circle of the dartboard. The core of embedding is that sustainability is integrated into business purpose and strategy. Research from the consultants Deloitte in 2011 found that over a fifth of Fortune Global 500 companies already have a clear, society-focused purpose underpinning their activities.15 Procter & Gamble, for example, amended their global mission and strategy in 2007 to say that their purpose is: ‘We provide branded products and services of superior quality and value that improve the lives of the world’s consumers, now and for generations to come.’ P&G’s values now include: ‘We incorporate sustainability into our products, packaging and operations.’

Top leadership has to believe in and ‘walk the talk’ on sustainability. Staff and other stakeholders need to hear their leaders explain regularly what it means for the business, why it is important, and how it is integrated. More importantly, they have to lead by example. As Sir Andrew Witty, CEO of GlaxoSmithKline said when lecturing at Cranfield in January 2012:

How do you, as an individual leader in your space, make a difference? What’s important? How are you going to set those expectations for the people who are around you? How are you going to set the language of your organisation? How do you set your incentive schemes? How are you thoughtful about sending substantive signals through your organisation that you are serious about running an organisation which is aligned with, not disconnected from, society?16

Embedding sustainability requires effective board oversight—the ‘governance of responsibility’. Some companies have a dedicated board committee or have extended the remit of an existing committee. Some have a lead non-executive director (NED) in charge. Some have a mixed committee of executives and non-executives.

It is also important that the approach to corporate sustainability matches the organisation’s strategic approach to doing business—to be real and relevant, sustainability should mirror the culture of the organisation as the strategy defines it in its objectives, approach, targets and measurements. Typically, companies have some over-arching sustainability commitment, such as Plan A at Marks & Spencer (see Chapter 11, Case study 11.2) and Zero waste to landfill at Xerox and Herman Miller. Companies need a process for getting each part of the business, each business function, to understand its significant social, environmental and economic impacts, and to embed sustainability within its operating plans.

Following the middle circle of the diagram around to the bottom, in addition to ‘top-down’ leadership and governance, companies with embedded sustainability seek to engage employees ‘bottom-up’, and engage their value chains from initial sourcing and suppliers through to customers and consumers.

The outer circle identifies operational enablers such as knowledge management17 and training (both formal education and experiential learning); stakeholder engagement, measurement and reporting, and communications; making use of the coalitions and collaborations that the business is involved in; and having a specialist function that increasingly is not seen as direct deliverer but as fulfilling ‘seven Cs’: Coordinator, Communicator, Coach, Consultant, Codifier, Connector and Conscience.

On the following pages, this embedding model is illustrated with the example of the fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) company Unilever.

Case study 1.1 Embedding sustainability in Unilever

Unilever is one of the companies at the forefront of embedding sustainability in the heart of business. This is not a new development. Indeed the founders of Unilever in the 19th century instinctively recognised that economic value can only be created if the needs of different stakeholders (consumers, customers, civil society, etc.) can be better met. William Lever’s insight was that the business would prosper if consumers actually benefited in their lives, and that the business would prosper if the workforce also prospered—there was a mutuality of interest.18 The company’s earliest vision was to ‘Make cleanliness commonplace, to lessen work for women, to foster health and contribute to personal attractiveness, that life may be more rewarding to people who use our products.’19

More recently, in the 1990s, Unilever was one of the first major companies to mature from corporate community involvement to a broader understanding of corporate social responsibility (CSR). Unilever’s CSR came from making explicit what was already being done as normal business practice in the management of the business. In the early days they concentrated on de-mystifying the jargon and encouraging the businesses around the world to have the confidence to explain what they were actually doing and how. This is important because it gave managers the confidence to get involved and created the solid foundation from which to set out on the sustainability journey.

One of the executives credited with developing the intellectual basis for Unilever’s subsequent sustainability commitments was Dr Iain Anderson, who worked for the company from 1965 to 1998, ending as a member of the executive committee after stints as chairman and chief executive of Unilever companies in agri-business, speciality chemicals and food. Guided by Anderson and others, the company developed strategies on fish, water and agriculture during the mid-1990s. This— combined with significant external pressures—led Unilever to co-found the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) in 1995 with the non-governmental organisation (NGO) WWF. Another long-serving senior Unilever executive André van Heemstra explained:

The Marine Stewardship Council goes back to the days that I was CEO of our frozen foods and ice cream company in Germany, Langnese-Iglo. It was 1995, the year of Brent Spar. At the same time Greenpeace had chosen fish depletion as a spear-point project. They did their homework, and rather than bothering with the complexity of fishermen and politicians they decided to tackle the issue downstream, at the processor level. Then following the leverage principle, they found out that Unilever was the leading fish processor in Europe, and that Germany was the largest fish processing country within the Unilever family. The next thing I knew was facing a sophisticated Greenpeace campaign. With the help of a superb English external adviser by the name of Simon Bryceson we took the initiative and started a public dialogue in Germany on fish depletion. This brought momentum, and at a certain point Simon came to see me together with Mike Sutton of the WWF. Mike came with the vision of the analogy from the Forestry Stewardship Council for fish, and it took him only 30 minutes to get me on board. I took the plane to Rotterdam the next day to convince Antony Burgmans, my then time frozen foods boss. And that is how the MSC was born.20

Around the same time Unilever established its Sustainable Agriculture Programme. In 2006, the then CEO Niall Fitzgerald and the then Corporate Responsibility director Mandy Cormack outlined what they had learnt in their respective roles about embedding responsibility in The Role of Business in Society: An Agenda for Action.21 More recently, in 2008, the company committed to buying 100% sustainable palm oil by 2015. These and related developments are seen as essential foundations without which Unilever's subsequent commitments would not have been feasible. In retrospect, they were, however, important but essentially still separate from much of the mainstream business and the development of future strategy.

Embedded within overall business purpose and strategy

In November 2010, Unilever launched its Sustainable Living Plan (USLP).22 This ten-year sustainability programme is central to the delivery of Unilever’s overall corporate strategy. The corporate strategy is set out in a document called ‘The Compass’ which commits the company to ‘double in size while reducing its environmental footprint.’ This makes Unilever one of the first FMCG companies to set itself the objective of decoupling growth from environmental impact. Indeed, Paul Polman, Unilever’s CEO since 1 January 2009, has said: ‘Sustainability is our business model.’23 The USLP makes a series of specific commitments to reducing the company’s environmental footprint while increasing the social benefit arising from its activities.24

According to Marketing Week in 2011, 'Like M&S, Unilever has set out to entirely reform the impact of its business on the planet and its people. While there is an aspect of social conscience behind the decision, there are also significant economic benefits.'25

A powerful example is delivered by Unilever’s hand-washing campaign across Asia and Africa. Studies have demonstrated that washing hands with soap is one of the most effective and inexpensive ways to prevent diarrhoeal diseases. This simple habit could help cut deaths from diarrhoea by almost half and deaths from acute respiratory infections by a quarter. In India, Unilever’s Lifebuoy soap hygiene education, Swasthya Chetna (Health Awakening), has touched the lives of more than 120 million people in rural areas. It has also delivered commercial benefits for the brand, driving up the sales of soap in districts where the campaign ran.

Leadership

Paul Polman has taken the lead on Unilever’s sustainability commitment. Those familiar with the company suggest that as a Dutch national, Polman is instinctively comfortable with sustainability. His task has been made easier because of the hard work done by his predecessor, Patrick Cescau, to simplify the corporate structure and create ‘one Unilever’. ‘One Unilever’ was a fundamental simplification project. In fact its formal title was ‘Simplification’. Certainly, Polman himself declared on becoming CEO that Cescau had put the wiring in place and that his job was to drive more electricity down the wires!

According to Forbes magazine:

In driving the plan, Polman has led from the front. He responds to emails from his senior executives, often even on Sundays. He follows an open door policy, encouraging employees to reach out to him and he communicates directly with all its global employees through email and videoconferences.26

Unilever insiders credit Polman with creating 'space' and giving 'permission' for more radical and ambitious targets on sustainability. Indeed, Marketing Week argues that, 'Sustainability, it's now clear, is the yardstick by which Paul Polman's tenure as chief executive of Unilever will be measured.'27 He has, however, made sure that the USLP is owned by senior management generally and by the Board, with key executives carrying the accountability for different goals within the plan. Polman reviews progress on the plan with his executive team every quarter.

Governance and Board oversight

Unilever has a Board committee made up of non-executive directors— the Corporate Responsibility and Reputation Committee—which is charged with ensuring that business is conducted responsibly and that Unilever’s reputation is protected and enhanced. It ensures that the Code of Business Principles and Unilever’s Supplier Code remain fit for purpose and are properly applied. The Committee meets quarterly. It comprises three independent non-executive directors: the British parliamentarian and former...