eBook - ePub

Buckingham

The Life and Political Career of George Villiers, First Duke of Buckingham 1592-1628

This is a test

- 542 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Buckingham

The Life and Political Career of George Villiers, First Duke of Buckingham 1592-1628

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Recounts the life of the first Duke of Buckingham, describes his relationships with James I and Charles I, and examines his role in English politics.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Buckingham by Roger Lockyer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Part One

The Apprentice Years

MENDOZA: Now good Elizium, what a delicious heaven is it for a man to be in a Prince's favour. O sweet God! O pleasure! O fortune! O thou best of life! What should I think? What say? What do? To be a favourite! A minion! To have a general timorous respect observe a man; a stateful silence in his presence; solitariness in his absence; a confused hum and busy murmur of obsequious suitors training [conducting] him; the cloth held up and way proclaimed before him; petitionary vassals licking the pavement with their slavish knees; whilst some odd palace lampreels [lampreys] that ingender with snakes and are full of eyes on both sides, with a kind of insinuated humbleness fix all their delights upon his brow. O blessed state! What a ravishing prospect doth the Olympus of favour yield.

John Marston, The Favourite, Act I, Scene v

Chapter One

1592–1616: 'The Gracing of young Villiers'

I

George Villiers, future Duke of Buckingham, was born at Brooksby Hall in Leicestershire on 28 August, 1592. The house, though much altered and extended, still stands on rising ground in the Wreake valley, just off the main road that runs from Leicester to Melton Mowbray. The back of the house looks across gently rolling, open country, but from the front there is not much to catch the eye except the medieval church, with its fine tower and crenellated parapet. John Leland, the sixteenth-century antiquary, who visited Brooksby in the course of his peregrinations, would find that little has changed over the past four hundred years. 'There lie buried in the church', he recorded, 'divers of the Villars', and many of their monuments are still there.1 On the northeast wall of the chancel, however, is a memorial that Leland could not have seen, for it is sacred to the memory of Sir William Villiers, who died in 1712. With him, as the inscription records, 'determined the male line of the eldest house of that honourable name', for he was the last representative of 'a race of worthy ancestors, upwards of five hundred years happily enjoying a great revenue in this county in a right noble and hospitable use thereof'.

The Villiers were indeed an ancient family, although Buckingham's enemies were only too eager to pour scorn upon his descent and to comment, sourly, that there was 'nothing more proud than basest blood when it doth rise aloft'. The name is, of course, French in origin, and it may be that the family was a branch of the Villiers who were Seigneurs de l'Isle Adam in Normandy. But whether or not they came over with the Conqueror they were certainly settled at Kinoulton, in Nottinghamshire, by the early thirteenth century. There they might have remained, but for the fact that Alexander de Villiers married the heiress to Brooksby, some nine miles due south, and is recorded in 1235 as holding land there — the first Villiers to be seated in Leicestershire.2

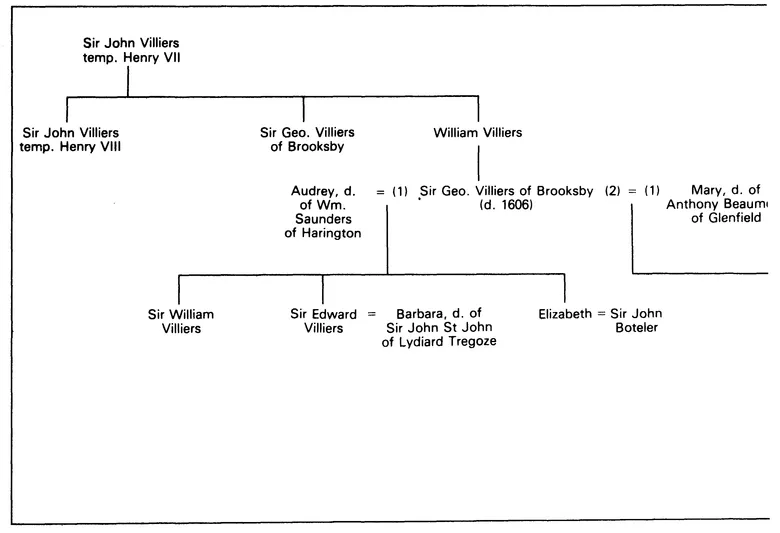

From then on Brooksby was handed down in the male line, and the Villiers lived — as Sir Henry Wotton, Buckingham's first biographer, delicately put it - 'rather without obscurity than with any great lustre', following the pattern of life common to gentry families all over England. They entertained friends and neighbours and arranged marriages with them; they added to their estates; they hawked and hunted; and they carried out the unpaid public duties with which they were entrusted by the reigning monarch. John Villiers, for example, served as sheriff for Leicestershire under Henry VII and was knighted for his pains. His son, another John Villiers, also served as sheriff and received the honour of knighthood, this time from the hands of Henry VIII. The second Sir John had no male heirs, and was succeeded by his brothers, the third of whom, William Villiers, married Collett, the widow of another Leicestershire gentleman, Richard Beaumont of Cole Orton. Collett presented her husband with the longed-for male heir, who was christened George. In due course he succeeded to the lands and lordships of Brooksby and Hoby, served as sheriff of Leicestershire in 1591, and was knighted by Queen Elizabeth two years later.3

Table 2. The Villiers family

When Leland visited Brooksby in Henry VIII's reign he observed that 'this Villars at this time is a man but of a 200 marks {£133 6s. 8d.] of land by the year'. Yet by the time Sir George inherited the property it was worth a good deal more. This was because his immediate predecessors had improved their estates by enclosing the arable lands and turning them over to sheep. The well-watered, open countryside was ideally suited to pasture farming, and with the demand for English wool reviving in Elizabeth's reign there was a great deal of money to be made out of this. But the profits were confined to the owners of land. The poor tenants - apart from the handful who found employment as shepherds — had no work and no way of keeping body and soul together now that the fields and commons which had previously afforded them a livelihood had been enclosed. Sheep, as Sir Thomas More observed, 'eat up and swallow down the very men themselves', and as the number of inhabitants decreased so their houses crumbled into dust. Brooksby was no exception. By 1584 the village had virtually disappeared; only the church and manor-house remained, as they do to this day, looking out over the peaceful pastures.4

Among Sir George's other properties in Leicestershire was Goadby Marwood. This had earlier belonged to the Beaumont family, but in 1575 the Beaumonts sold it to Sir George, and it remained in the possession of the Villiers for the next hundred years. The Beaumonts and the Villiers, being near neighbours, had long been connected by ties of friendship and marriage, and these were drawn even closer after the death of Sir George's first wife, Audrey Villiers, in 1587. He was still a relatively young man, not much above forty, and widowhood held out no obvious attractions to him. It was probably while he was visiting his Beaumont cousins at Cole Orton that he met Mary Beaumont, who came from a younger, and poorer, branch of that family and was serving as companion and waiting-woman to her richer relatives. Mary Beaumont had no fortune, but by all accounts she was a beautiful and attractive woman, and it was not long before she became Sir George's second wife. Many years later, when she was the mother of the most powerful man in England, and a wealthy, influential countess in her own right, the enemies of Buckingham took delight in exaggerating her lowly origins.

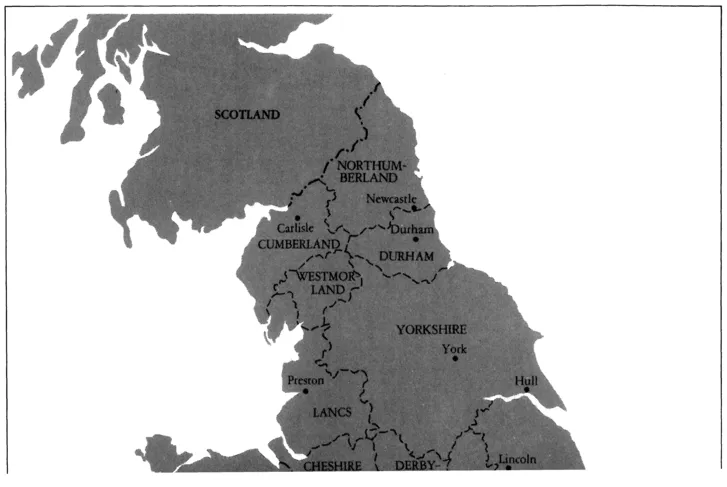

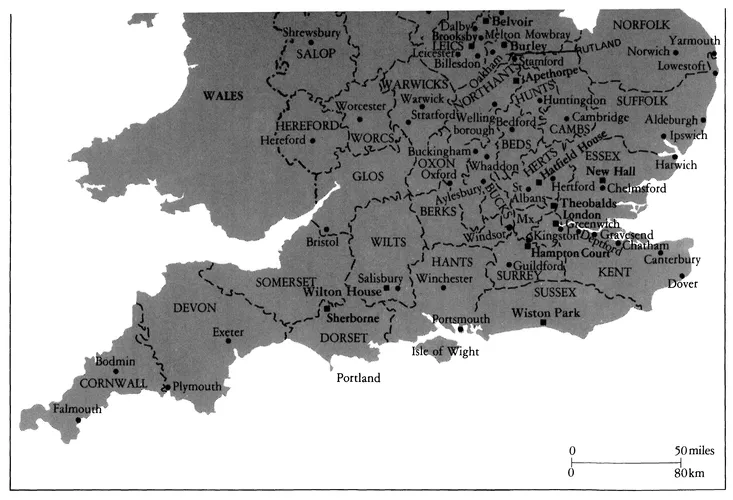

Map 1. England, showing places of significance in Buckingham's life

Anthony Weldon declared that she came from a mean family, while Roger Coke (grandson of Sir Edward, the great lawyer) reported a rumour that she had been 'entertained in Sir George Villiers's family in a mean office'. Coke adds that 'her ragged habit could not shade the beautiful and excellent frame of her person', and that Sir George was so struck by Mary's looks that he persuaded his wife 'to remove her out of the kitchen into her chamber, which with some importunity on Sir George's part, and unwillingness of my lady, at last was done'. Soon after this, if Coke's account is to be believed, Audrey Villiers died, and Sir George was now dependent upon Mary for solace and companionship. Coke relates how he soon 'became very sweet upon' her, and gave her £20 with which to buy a dress that would display her fine figure. This she did, and the result obviously fulfilled all Sir George's expectations, for his 'affections became so fired that to allay them he married her'.5

Coke's account of the development of the relationship between Sir George Villiers and Mary Beaumont may be well founded, but there is no basis for Weldon's slur about her lowly origins. As far as descent was concerned, she could match, if not excel, Sir George's own, for although her father, Anthony Beaumont of Glenfield, was simply a Leicestershire gentleman, he was a direct descendant in the male line of the Barons Beaumont, and, in the female, of Henry III, King of England. Sir George, of course, married Mary primarily for her beauty and not her family connexions, but he must also have felt the need of someone to look after his family of two sons and three daughters. Whether the children welcomed Mary as a stepmother is not recorded, but the fact that Buckingham maintained close and friendly relations with his halfbrothers and sisters suggests that Sir George's two families got on well together, and this would hardly have been possible if Mary had been treated as an interloper. She brought little with her apart from her beauty, but there was one valuable addition to the household in the shape of Thomas Vautor, who had been retained as a musician in her father's house, and now followed Mary to Brooksby. When, many years later, Vautor published a collection of songs, he dedicated it to Buckingham, since, as he recalled, 'some were composed in your tender years and in your most worthy father's house (from whom, and your most honourable mother, for many years I received part of my means and livelihood)'.6

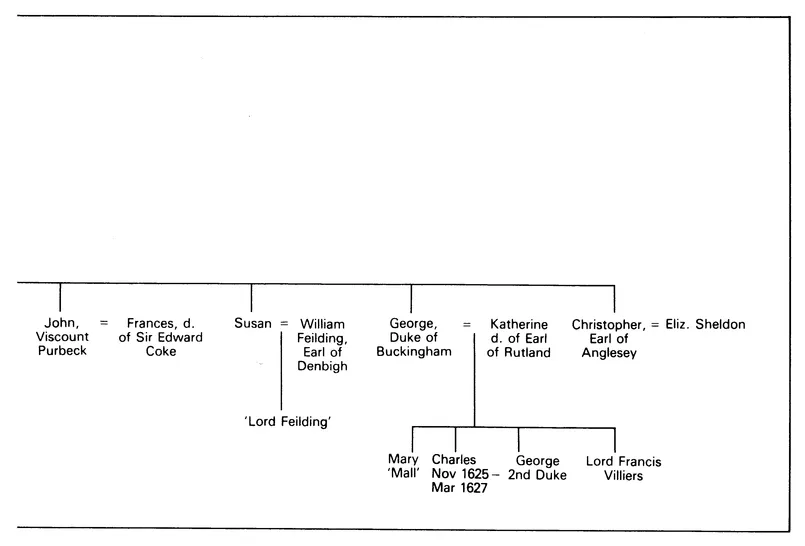

The date of Mary Beaumont's marriage to Sir George is unknown, but can hardly have been later than 1590 (at which time, of course, he was still plain Mr Villiers). Her first child by him was a boy, John Villiers; her second a daughter, Susan. Buckingham, named after his father, was the third child, and he was followed by another son, Christopher. Brooksby, which was not a large house, must by now have been bulging at the seams. There was, however, a second house, at Goadby, and the fact that a number of Sir George's children were baptised or buried there suggests that it was used as a home. In any case the male members of the family were probably sent away to school as soon as they reached an appropriate age. This was certainly the case with Buckingham, and there is no reason to assume that he was treated any differently from his brothers and half-brothers. Local schools were increasing in number in the sixteenth century, and were at first patronised mainly by yeomen, artisans, and small shopkeepers. But during Elizabeth's reign the sons of gentlemen and even peers began attending local schools, and among these was Buckingham. Leicester and Melton Mowbray were both good centres and reasonably near to Brooksby, but Sir George sent his ten-year-old son across country to Billesdon. This was because the local vicar, Anthony Cade, had already made a reputation for himself as a man of learning and integrity. The vicarage at Billesdon served as a school, and Cade, as he recorded himself, 'was thought worthy to be employed in the training up of some nobles and many other young gentlemen of the best sort. . . in the learned tongues, mathematical arts, music, and other, both divine and human, learning'.7

Buckingham was not a natural scholar. He preferred the active life to the contemplative, and subsequently blamed his lack of scholarship for his inability 'to manage those moral and natural parts which God had blessed him withal'. According to Wotton he was taught the principles of music and 'other slight literature' at Billesdon. No doubt he also struggled with the rudiments of Latin, though in later years he was to disclaim any ability in the language. But Cade would have made it his first task to instil in his pupils the principles of the Christian religion as exemplified in the doctrines of the Church of England, and his success in this particular instance may be indicated by the fact that while Buckingham was to develop close connexions with a number of catholic families during his years in power, he never abandoned the orotestant faith in which he had been brought ud.8

Although Buckingham probably learnt little at Billesdon he developed an abiding affection for Anthony Cade. When he became favourite he introduced Cade to James I, and some years later was instrumental in procuring for him the offer of what Cade described as 'a right famous and noble place, to raise my fortunes and exercise my ministry in (the like whereof many have sought with great suit, cost and labour, and have not found)'. Whatever this place was, Cade — who practised humility as well as preaching it - declined the offer, but he showed his gratitude by dedicating his published sermon on 'St Paul's Agony' to his former pupil. Some years later Buckingham arranged for him to be presented with the living of Grafton Underwood, which he held along with Billesdon. Cade was already a pluralist, and - contrary to what one might assume from his religious leanings - seems to have had no qualms about holding more than one living. The benefits to a scholar were only too apparent, for, as he told the Lord Keeper, this increase of means would enable him 'both to live in better sort without want (and thereby without contempt), and especially to furnish me with many useful books of all kinds and sides: in perusing, examining and extracting the quintessence whereof is my daily labour and my greatest worldly contentment'.9

Buckingham had been under Anthony Cade's tuition at Billesdon for three years, and was by now thirteen, when, in January 1606, his father died. Sir George Villiers, at the time of his death, was a man of wealth and property, but the greater part of this went to his eldest son by his first marriage. Mary Villiers now had to move out to the dower house at Goadby Marwood. She took George, and possibly her other children, with her, and from then on Goadby, rather than Brooksby, was Buckingham's home. Mary had a life interest in the house at Goadby Marwood, with three hundred and sixty acres attached to it, and also a jointure of £200 a year, so she was far from destitute. Furthermore, in June 1606, less than six months after the death of her first husband, she married Sir William Reyner. This marriage was of brief duration, since Reyner died in November of that year, but she was presumably entitled to her dower out of his lands, and this must further have improved her financial position. But money can hardly have been plentiful, and Wotton's reference to Buckingham's 'beautiful and provident mother' suggests that she counted her pennies carefully. Mary Villiers can have had no easy task in bringing up her family at Goadby, for in later years Buckingham was to recall his childhood as a time 'when I did nothing else but unreasonably and frowardly wrangle'. Even when Buckingham was a grown man he was still, in his mother's eyes, 'the same naughty boy, George Villiers', but she loved him deeply and he returned her affection in full measure. He never ceased to be thankful for the 'more than ordinary natural love of a mother, which you have ever borne me', and could not be happy until she had given him 'as many blessings and pardons as I shall make faults'.10

As Buckingham grew up it became apparent that he had inherited both his mother's beauty and his father's dignified bearing. Mary Villiers, recognising that her son was no scholar, 'chose rather to endue him wi...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Part One The Apprentice Years

- Part Two Buckingham in Power

- Bibliography

- Index