![]()

Chapter 1

The Twenty-first Century Parking Problem

You don’t know what you’ve got till it’s gone. They paved paradise and put up a parking lot.

—JONI MITCHELL

Children first learn about free parking when they play Monopoly. The chance of landing on free parking is low, about the same as the chance of going to jail. Monopoly misleads its players on this score, however, because parking is free for 99 percent of all automobile trips in the U.S.1 This book will argue that another kind of deception is also at play on the Monopoly board because in the real world, there is no such thing as “free” parking. The cost of parking is hidden in higher prices for everything else. In addition to the monetary cost, which is enormous, free parking imposes many other hidden costs on cities, the economy, and the environment.

Why is most parking free to the driver? When only the rich owned cars at the beginning of the twentieth century, motorists simply parked their new cars at the curb where they had formerly tethered their horses and carriages. But when car ownership grew rapidly during the 1910s and 1920s, the parking problem developed. Curb parking remained free (the parking meter was not invented until 1935), but there were no longer enough spaces for everyone to park whenever and wherever they wanted. Drivers circled in vain looking for a vacant curb space, and their cars congested traffic. In the 1930s, cities began to require off-street parking in their zoning ordinances to deal with the parking shortage, and the results were miraculous. One delighted mayor reported:

We consider zoning for parking our greatest advance…. It is working out exceptionally well, far better than we had expected. In brief, it calls for all new buildings to make a provision for parking space required for its own uses.2

This sounds like a good idea. In one sense, it was a good idea. Requiring all new buildings to provide ample on-site parking did solve one problem—the shortage of free curb parking—but the solution soon created new problems. Urban planners began to assume that most people would travel everywhere by car, park on-site while they worked, shopped, or dined, and then drive on to their next destination. Cities began to require each site to provide its own parking lot big enough to satisfy the expected peak demand for free parking, and most commercial buildings are now required to provide a parking lot bigger than the building itself. The required parking lot at a restaurant, for example, usually occupies at least three times as much land as the restaurant itself. Off-street parking requirements encourage everyone to drive wherever they go because they know they can usually park free when they get there: 87 percent of all trips in the U.S. are now made by personal motor vehicles, and only 1.5 percent by public transit.3

If drivers don’t pay for parking, who does? Everyone does, even if they don’t drive. Initially the developer pays for the required parking, but soon the tenants do, and then their customers, and so on, until the cost of parking has diffused everywhere in the economy. When we shop in a store, eat in a restaurant, or see a movie, we pay for parking indirectly because its cost is included in the prices of merchandise, meals, and theater tickets. We unknowingly support our cars with almost every commercial transaction we make because a small share of the money changing hands pays for parking. Residents pay for parking through higher prices for housing. Businesses pay for parking through higher rents for their premises. Shoppers pay for parking through higher prices for everything they buy. We don’t pay for parking in our role as motorists, but in all our other roles—as consumers, investors, workers, residents, and taxpayers—we pay a high price. Even people who don’t own a car have to pay for “free” parking.

Off-street parking requirements collectivize the cost of parking because they allow everyone to park free at everyone else’s expense. When the cost of parking is hidden in the prices of other goods and services, no one can pay less for parking by using less of it. Bundling the cost of parking into higher prices for everything else skews travel choices toward cars and away from public transit, cycling, and walking. Off-street parking requirements thus change the way we build our cities, the way we travel, and how much energy we consume. All the required parking spaces use up land, spread the city out, and increase travel distances. Free parking also reduces the price of driving wherever we want to go, so the increased travel distances combined with the reduced price of driving make cars the obvious choice for most trips. Because highway transportation accounts for half of U.S. oil consumption, which is a quarter of the world’s oil production, American motor vehicles now consume one-eighth of the world’s oil. Free parking helps to explain this extreme automobile dependence, rapid urban sprawl, and extravagant energy use.4

Parking affects both transportation and land use, but its effects are often overlooked or misunderstood. Many people see urban problems— congestion, pollution, decay, and sprawl—but even the most ferocious critics of cars often fail to connect these problems with parking policies. Consider the apocalyptic titles of these jeremiads against the car: Autokind vs. Mankind, Car Mania, Dead End, The Pavers and the Paved, and Road to Ruin.5 Off-street parking requirements contribute to the automobile-and-asphalt dominance the authors criticize, but none of the books even mentions parking. Parking is a blind spot in most studies of automobile transportation. Whether polemical or analytical, most books about cars and cities ignore the role that parking plays in both transportation and land use.

Journalists occasionally write about parking, usually with a critical tone. Here is New York Times columnist David Brooks’s description of a shopper’s trip to the mall in suburban Sprinkler City:

He steps out into the parking lot and is momentarily blinded by sun bouncing off the hardtop. The parking lot is so massive that he can barely see the WalMart, the Bed Bath & Beyond, or the area-code-sized Old Navy glistening through the heat there on the other side. This mall is…so vast that shoppers have to drive from store to store, cutting diagonally through the infinity of empty parking spaces in between…there are archipelagoes of them—one massive parking lot after another surrounded by huge boxes that often have racing stripes around the middle to break the monotony of the windowless exterior walls.6

Brooks describes a scene that is all too real, and many people concerned about sprawl decry the expanses of land used by big-box retail. But few people realize that cities require the developers of these “dark Satanic malls” to provide the massive parking lots that remain nearly empty much of the time.7

Because I want to call attention to our mistaken parking policies, I toyed with alarmist titles like Aparkalypse Now or Parkageddon. I eventually settled on the more sober The High Cost of Free Parking because this oxymoron captures the conflict between free parking and its hidden cost. In this book I show that “free” parking distorts transportation choices, debases urban design, damages the economy, and degrades the environment. I argue that American cities have made devastating mistakes with their parking policies, and I propose reforms designed to undo the damage caused by nearly a century of bad planning.

The Car Explosion

Coming to grips with the parking problem is essential because the rest of the world is poised to repeat America’s mistakes. America adopted the car much faster and to a far greater extent than other nations, and many factors help to explain this phenomenon—abundant land, rapid population growth, low fuel prices, and high incomes, among others. Abundant free parking also contributes to our high demand for cars because it greatly reduces the cost of car ownership. And because we own so many cars, we need lots of land to park them. We can speculate about the amount of land the whole world will need for parking if other nations ever acquire as many cars as Americans owned at the end of the twentieth century.

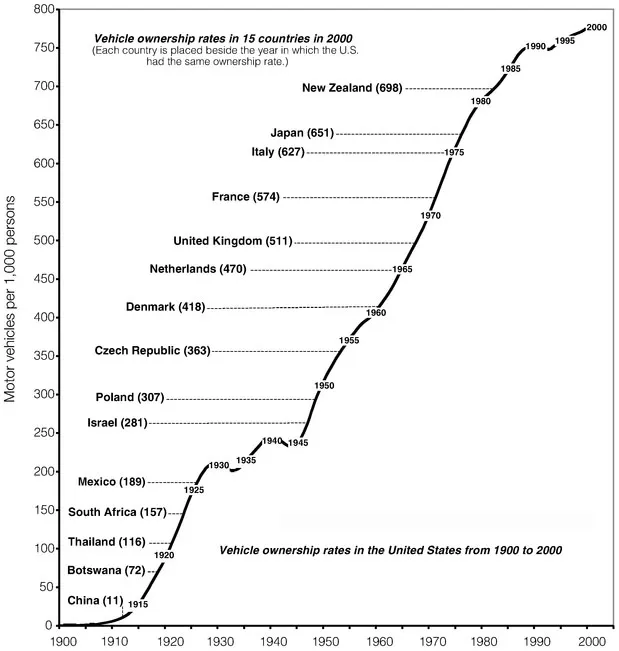

The first American gasoline car was sold in February 1896.8 By 2000, Americans owned 771 motor vehicles per 1,000 persons. Figure 1-1 shows the U.S. vehicle-ownership rates (motor vehicles per 1,000 persons) from 1900 to 2000. Apart from dips during the Depression, World War II, and the early 1990s, ownership rose rapidly. Fifteen other nations’ vehicle-ownership rates in 2000 are placed in the graph beside the year in which the U.S. had the same rate. In 2000, France had the same vehicle-ownership rate as the U.S. in 1972, Denmark the same as the U.S. in 1961, and China the same as the U.S. in 1912.9

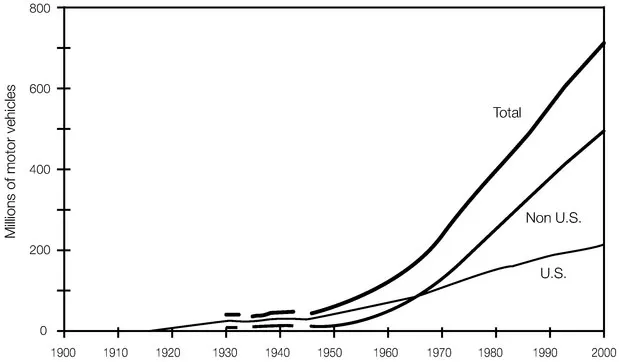

China is now the world’s fourth-largest market for new cars (after the U.S., Japan, and Germany), but the U.S. still added more than twice as many vehicles during the 1990s (29 million) as China owned in 2000 (13 million). Other nations are, however, gaining on the U.S. Since 1950 the vehicle population has grown more than twice as fast outside the U.S. as inside (see Figure 1-2).10 And yet, taken together, in 2000 the world outside the U.S. owned only 89 vehicles per 1,000 persons—the U.S. rate in 1920. But just as the U.S. vehicle-ownership rate doubled in the five years after 1920, rapid growth may also occur soon in other countries.

The 6.1 billion people on earth in 2000 owned 735 million vehicles. Imagine what would happen if all the countries on earth ever achieve the same vehicle-ownership rate as the U.S. in 2000: there would be 4.7 billion vehicles even if the human population does not increase.11 A parking lot big enough to hold 4.7 billion cars would occupy an area about the size of England or Greece.12 If there are four parking spaces per car (one at home, and three more at other destinations), 4.7 billion cars would require 19 billion parking spaces, which amounts to a parking lot about the size of France or Spain.13 More cars would also require more land for roads, gas stations, used car dealers, automobile graveyards, and tire dumps.

Figure 1-1. Vehicle Ownership Rates: The United States from 1900 to 2000 and 15 Other Countries in 2000 (Motor vehicles per 1,000 persons) Source: Tables H-1 and H-2 in Appendix H.

Figure 1-2. Number of Motor Vehicles on Earth Source: Table H-1 in Appendix H.

If the past trends in vehicle ownership continue, the world will have more than 4.7 billion cars well before the end of the twenty-first century. Even if the vehicle population grows by only 2 percent a year, it will increase from 735 million in 2000 to 5 billion in 2100. Can the world supply all the fuel needed to power 5 billion cars? Will humans be able to breathe the fumes coming out of 5 billion exhaust pipes? And where will 5 billion cars park?

These questions are not meant to sound alarmist. A simple projection is often a poor forecast because technology and policy can change. For example, horse-drawn carriages befouled cities a century ago. In New York City in 1900, horses deposited 2.5 million pounds of manure on the streets every day.14 Projected growth in transportation demand made a public health disaster seem inevitable, but then the horseless carriage solved that problem. Now, horseless carriages create their own problems, but new solutions will arrive. Improved technology will increase fuel efficiency and reduce pollution emissions, but technology alone is unlikely to solve the parking problem. Regardless of how fuel efficient our cars are or how little pollution they emit, we will always need somewhere to park them, and the average car spends about 95 percent of its life parked.15

This book proposes new policies to solve our parking problems. After all, we don’t want to see France or Spain paved for a parking lot. Before proposing any solutions, however, I will first explain what I believe creates most parking problems: the treatment of curb parking as a commons.

The "Commons" Problem

Free curb parking presents a classic “commons” problem. Land that belongs to the community, and is freely available to everyone without charge, is called a commons. City life requires common ownership of much land (such as streets, sidewalks, and parks), but the neglect and mismanagement of common property can create serious problems. Aristotle observed:

What is common to the greatest number has the least care bestowed upon it. Every one thinks chiefly of his own, hardly at all of the common interest.16

The archetypical commons problem occurs on village land that is freely available to all members of a community for grazing their animals. This open-access arrangement works well in a small community with plenty of grass to go around. But when the community grows, so does the number of animals, and eventually, although it may take a while to notice it, the land is overrun and overgrazed. Harvard economist Thomas Schelling describes the problem: