CHAPTER 1 The Study of Group Goals

One often hears members of a group say (with vigor) that their unit has done a good job. Their tone and their comments about the group’s performance reveal that the accomplishment pleases them. The source of their satisfaction, they make clear, is in the unit’s attainment of a preset goal. On a later occasion, one may hear the same members assert that their group has done poorly, that they are dissatisfied, yet, their group’s output is exactly the same as it was when the members were pleased. Apparently in the interim members have changed their group’s goal, the criterion they use in evaluating the group’s work. A sense of success and pride among these participants, it is plain, depends not only on the group’s score, it depends as well on what they expect or intend that score to be.

Members’ awareness of accomplishment and their feeling of satisfaction are generally recognized as good things in themselves. In addition, a gratifying success gives rise to other useful properties in a group: members develop a stronger desire for group success, they work harder, they cordinate their efforts more effectively, they have less strain in interpersonal relations, they are more attracted to membership, and the group in fact becomes more productive. A success can foster conditions conducive to further success. A dissatisfying failure, in contrast, may invoke properties quite different from those just mentioned; thus a failure may lead to further failure, a spiraling of events that can be difficult to reverse. It is necessary in short that a group have an appropriate goal if it is to develop the qualities most favorable for its effective operation and survival.

The ability to interpret behavior in working groups would be considerably improved if there was a better understanding of the conditions that determine why a group chooses one goal rather than another, a reasonable goal rather than an unreasonable one. The contents of this volume concern the goal members establish for their group and are mainly focused on a particular kind of goalcalled a group level of aspiration. It is intended to examine the origin of this aspiration, to spell out its value in the continuing work of the group, and to observe how it affects and is affected by members’ motives to achieve success. Such motives, it is assumed, are not merely dispositions to obtain personal gains; they are also inclinations to help the group attain satisfactory outcomes. The primary questions can be stated simply: What causes members to select a particular goal for their joint endeavor? Why do members become involved in the achievement of their group?

There is not a complete absence of information on these matters. But most relevant research has been based on the assumption that a member thinks only about his own interests while participating in a group: he competes, bargains, negotiates, or cooperates with colleagues in order to achieve personal ends. Group objectives, in this view, are only an indirect product of the agreements among self-centered individuals. And, when the members of goal-setting bodies indulge in self-seeking, group objectives do become a compromise among preferences based on personal motives. When one observes group decision making, however, one notes that members often suppress any inclination to put their own needs first, pay little attention to each other’s personal desires, and believe it to be an ethical matter to behave in this way. They concentrate instead upon what the total group should do. Choices are made on the basis of what is “good for the group,” a matter which can itself generate disharmony and differences. It is understandable then that members’ motives to achieve success may not only be dispositions to obtain personal rewards, but may also be inclinations to attain satisfactory outcomes for the group.

Suppose that all the members have a say in the selection of a future goal on a task they have jointly performed a number of times. Several sets of circumstances other than self-focused negotiations might affect their choice.

1. The participants have to decide what score they can reasonably expect their group to attain. They will want this goal to be possible, yet it should not be too easy. The unit’s past performance suggests what its next score might very well be, but there is always the potentiality that the skill of members will improve; or a change in group structure, in assignments, in leadership, in procedure of work, in training, or in the enthusiasm of members, might also make a difference. Are previous scores always the most reliable indicators of the group’s true competence? If the group is changed in some way, should expectations be changed?

2. Some levels of group achievement are more satisfying than others. In a Western society larger rewards are given for, and more satisfaction develops from, accomplishing harder tasks. Pride in group or “team spirit” are not wholly mythical consequences of a success on a challenging task. A successful group, for example, might welcome a greater challenge in the future.3. Members frequently receive information from external sources that have an impact, intended or otherwise, upon future plans for the unit. Because the product of a group is seldom for the use of members alone, participants often suit their objectives to the wishes and reactions of agents outside the group.

4. The members of a group may differ in the strength of their desire to have their group achieve success. A unit’s past history of success or failure will doubtless influence such a group-oriented motive but other circumstances also have an effect. Those in a better organized or more attractive collectivity might have a stronger desire to do well. Members who feel that the work of their group is important in itself or of use to a larger organization may be more eager to ensure that the group sets proper yet satisfying goals.

5. Even the personal dispositions a member brings to his group, or develops there, can determine his plans for the group. If he is the type who appreciates challenging tasks, whether alone or with others, involvement in the group’s endeavors and his reactions to its performance may be quite different from what they would be if he dislikes competing against standards of excellence.

The nature of the goal can, in turn, determine what events occur within the group: its level of performance, the pride of members in their organization, their personal self-regard, the aims they develop for their own jobs, the attitudes and beliefs they invent about the organization or its work, and the survival of the unit itself.

In sum, the goal men choose for their group can be influenced by conditions in the group as well as their individual motives, and their choice has a potentially strong effect upon the life of the group. Group leaders and members commonly develop concepts for use in thinking about these issues and create their own explanations about why things happen as they do. There is, however, little scientific understanding of such matters.

Approach to The Study of Goal Setting

Given the questions we wish to answer, the results of previous investigations are largely truncated. On the one hand, students of social institutions have written about group goals but have avoided making assumptions about motives of members. They have been interested in the abstract meaning of the term goal, how one discovers what the goal of a group is (if any), who sets the goal, and the character of multiple goals within a larger organization. Students of individual motives, on the other hand, have had little interest in groups, except as they provide a locus for arousing particular needs. They have studied the nature of a member’s personal motivation, but not the effect of a group’s goal on thismotivation. The study of the origins (and effects) of group goals has largely fallen between disciplinary chairs.

At first glance, one might think that investigations of group decision making or problem solving are pertinent to present purposes. However, most such studies do not require participants to commit themselves to their decisions, or to live with them; instead, the studies concentrate upon the effects of reasoning, cognitive clarity, or interpersonal influence among members.

Investigations of “risk taking” by groups (6, 71, 72 ) reveal that group decisions are often quite different from personal and private judgments made by members prior to a group discussion. These experiments appear to be related to the present interests since they concern choices in which there is a greater or lesser probability of favorable or unfavorable consequences for somebody. Apparently groups make more “risky” choices than individuals do, but not always. As the reasons for these interesting findings are not yet understood, it is not possible to say what the precise relationship between them and the results in this volume will turn out to be.

Studies in the dynamics of groups, particularly those on the nature of cooperation, cohesiveness, and group performance, have been useful in ways that will be evident later as pertinent findings are presented when they relate to a given topic.

All in all, the results of prior research provide few leads suggesting where one might best begin to study the origins of group goals and the interest of members in these goals. In the absence of descriptive data and relevant theory, it appeared that a study of how a group goes about establishing its future expectations would initially be most useful. It was decided to begin with observations of simple experimental groups in the laboratory and to move on thereafter to the study of group properties, taking them one by one, that appear to have an impact on the selection of a group’s goal. This plan was accompanied by several working assumptions.

First, the ends that members select for their group were conceived as part of the unit’s ongoing procedure in doing work, subject to change as a result of feedback on the group’s performance.

This assumption is in accord with a proposal made by Lewin (46) in an essay on social diagnosis and action. As he saw it, a plan for group work exists when the group’s purposes have been defined, a relevant goal and the means for its attainment have been determined, and a strategy for action laid out. Assuming that this plan should be flexible and subject to change as actions by the group make this necessary, he displaces the basic principles of feedback to the social realm. Emphasizing the major proposition in such self-steering—that a means exists for determining the desired performance and the proximity of this performance to the desired state—he then asserts that “a discrepancy between the desired and the actual direction leads automatically to a correction of actions or to a change in planning.”

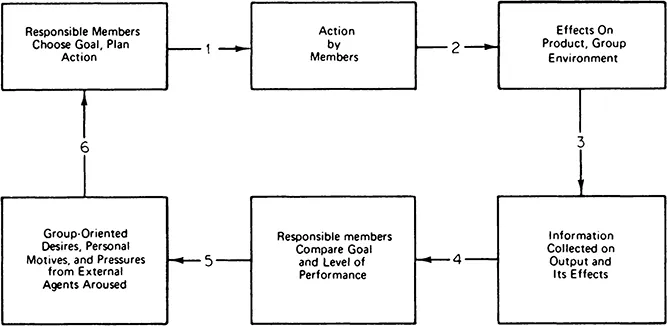

Fig. 1-1 The process of feedback in a group.

Typical stages in his model of feedback are shown in Fig. 1-1: (1) Decision makers establish a goal and the methods to be used in attaining it. (2) Action is taken which has effects upon the group and on relevant conditions outside the group. (3) Information about the movement of the group toward its goal (the output of the group) is obtained and reported back to the decision makers. (4) The decision makers observe any deviation between the original goal and the group’s performance. (5) Desires members have for the group, their personal motives, and pressures arising from external agents influence the members’ reactions to this evaluation (this stage is not explicitly stated but is implied in the model). (6) If the deviation between score and expectation is greater than is tolerable, the decision makers take steps to reduce this discrepancy either by changing the nature of actions in the future or by changing the group’s goal. The important point is that the meaning of the group’s performance is not simply something in the score itself or in the group itself but in the relationship between performance and what is desired. When a feedback loop exists, that is, when members obtain evidence about the group’s performance on a series of attempts, we can expect a type of motivated behavior to be invoked.

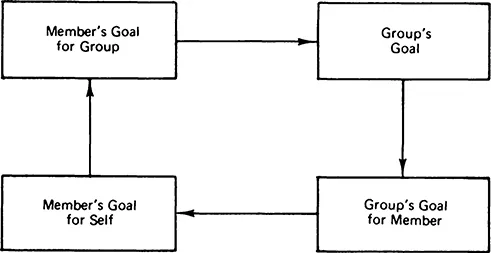

Fig. 1-2 Relations among individual and group goals.

Second, a group’s decisions and actions are the behaviors of individuals, even when the decisions are joint agreements among many persons and lead to later teamwork among them. In order that one not mix levels of discourse between group and individual goals, then, it is necessary that one recognize the four types of relations at work, as shown in Fig. 1-2.

The goals and their relationships in Fig. 1-2 remind us that there can be a circular-causal relationship among such and that some (in the left column) are concepts about an individual and others (in the right column) are properties of a group. It is plausible to believe that different matters determine the nature of the goals within each of the four boxes. Planning of research must recognize the distinctive nature of these different variables.

Third, and most important, it was decided that a group level of aspiration was a suitable type of goal for initial study, assuming that a group aspiration may be conceived to be an analog of a personal aspiration. A group level of aspiration is the score members expect their group will attain in the future.

There were several reasons for this decision: the origin and changes in a level of aspiration give operational meaning to the stages in the feedback model discussed above; a fairly standardized procedure exists for studying the level of aspiration and related concepts; there is evidence on hand that a group can influence a member’s personal aspiration by establishing a group level of aspiration; and findings from prior research on individual aspirations provide a way of judging intuitively if groups, when they set goals, differ in some way from solo individuals, when they set goals.

It is quite meaningful to ask a group as a single entity to perform a task over and over, to obtain a group score, and to require that the members agree upon a level of aspiration for their group prior to each trial. In addition, each member can be asked, privately, what he prefers the group’s aspiration to be, so that the effects of personal desires or of properties of the group can be examined without the confounding created by a group discussion. Certain ground rules are necessary for treating a group in this fashion, these are described in the next chapter. There is a potential problem, however, in the use of aspiration theory for the present purposes. Does the level of aspiration function both as a criterion for evaluating the performance of the group and as an objective for guiding performance, or does it have one of these functions under certain conditions and the other function under different conditions? These question will remain unanswered at the outset, and during most of this report. The answers are provided in Chapters 4 and 10.

These decisions were made before research began. Later, it became clear that several others followed naturally. In a typical experimental routine, we asked members to select a group level of aspiration and provided them with information about the score of the group but not the member’s own performance for each trial. In such a situation a member’s cognitions are limited to those concerning the output of the group and he thus develops, can only develop, an interest in the satisf...