![]()

1

Introduction

Democracy in Latin America: Promises and Perils

Richard L. Millett

Mark Twain once observed, “Everybody talks about the weather but no one does anything about it.” Today that phrase might be altered to “Everybody talks about democracy, but few seem able to define it.” Democracy has become a global buzzword, a concept used to evaluate governments, to condemn those who allegedly subvert or ignore it; democracy is virtually always praised as an unquestionable good. Terrorists, our leaders assure us, hate democracy, while virtually every politician in the Western Hemisphere today proclaims his allegiance to this concept. Even North Korea proclaims that it is “the People’s Democratic Republic of Korea.” While examples such as this may be scoffed at, attempts to precisely determine what governments are democratic and whether they are becoming more or less so produce little consensus and frequent acrimonious debates, which tell us more about the ideology of the participants than about the nation involved.

Winston Churchill once declared that “[n]o one pretends that Democracy is all wise. Democracy is the worst form of government except for all the others that have been tried” (James 1974, 174). Frequently quoted, but rarely examined, this admission of democracy’s weakness and limitations has proved all too true in practice. As a system, it is usually inefficient—at times virtually chaotic—and able to bring forth the worst, as well as the best, characteristics of the human race. It can play upon fears and misconceptions; exploit ethnic, racial, and religious differences; sanctify popular prejudices; and justify denials of justice to minorities. Governments that arrive to power through a democratic process do not necessarily govern democratically.

But if all these dangers exist, the other part of Churchill’s quote is also true. Democracy is based upon the assumption that all power should be limited—limited by time, limited by countervailing power, limited by the rule of law. Democracy, as James Madison observed in the Tenth Federalist, is designed to promote majority rule with respect for minority rights. It is a system where those who lose today’s struggle for power are supposed to be guaranteed another chance tomorrow, and those who exercise power will be held accountable for their actions. Perhaps its greatest strength, at least in theory, is its ability to learn from and rectify mistakes, to adapt to changing conditions.

This volume is designed to build on Churchill’s dictum, to examine the progress towards, but also the shortcomings of and dangers to, democratic rule in Latin America. While it generally assumes that progress towards more democratic institutions is desirable, it also accepts that such progress will vary in many ways from society to society, that one size does not fit all. Rather than attempting to impose a single definition and promote a single model, the authors hope to stimulate discussion as to its nature, applicability, strengths, and weaknesses in varied circumstances. In his 1982 volume, Democracy in Latin America, Hoover Institute scholar Robert G. Wesson observed:

In recent decades the contest between democratic and oligarchic tendencies has become more complex and has taken on new dimensions. The opposition to democracy has acquired more purpose and confidence and has come to seem more of a concerted tendency, less a mere expression of the hierarchic society or a response to the ineffectiveness of democratic structures.

(Wesson 1982, vii)

In the twenty-first century, this situation has changed dramatically. Relatively freely elected governments have been installed everywhere except Cuba, and even there the departure of Fidel Castro from supreme power offers the possibility of a transition to a less authoritarian rule. Polls consistently show strong popular support virtually everywhere for democratic governments. The Organization of American States had adopted the “Democratic Charter” pledging member states to the support of democratic rule throughout the hemisphere. In most nations, the media and labor unions are able to operate relatively freely, if not always with adequate personal security. Military coups seem largely a thing of the past, though events in Honduras raise troubling questions about military collusion with disaffected civilian sectors. Elections are usually monitored by both national and international observers, and despite some controversy, notably in Mexico and Venezuela, the voting process is widely seen as fair and impartial. If not exactly flourishing, electoral democracy seems at least to be in the process of establishing itself as the dominant political system in the hemisphere.

However, serious problems remain. As Larry Diamond, co-editor of The Journal of Democracy, reminds us, “If democracies do not more effectively contain crime and corruption, generate economic growth, relieve economic inequality, and secure freedom and the rule of law, people will eventually lose faith and turn to authoritarian alternatives” (Diamond 2008, 37).1 All of these factors are present in today’s Latin America. Judicial systems are often weak and/or corrupt, and citizen security has deteriorated in many nations. Incumbent presidents alter and manipulate constitutions to permit their own reelection. Corruption continues to be a serious issue despite the growing transparency of the political process. While security forces have lost most of their political power, their place at times seems to have been taken by organized criminal groups, and military coups at times have been replaced by coups led by angry urban mobs. Latin America’s theoretically independent election authorities are increasingly subject to manipulation by governments in power attempting to constrain or eliminate political rivals, manipulate the electoral registry, and inhibit external observations of the electoral process.

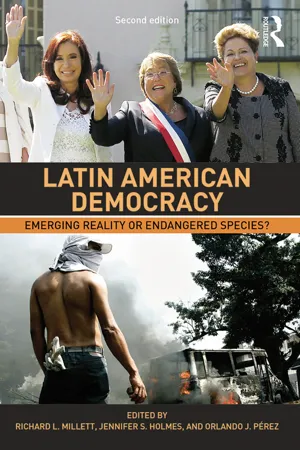

Notable progress has been made in incorporating long-neglected and/or exploited groups, notably indigenous peoples and women, into the political process. Women currently hold the presidency in Argentina, Costa Rica, and Chile, while Bolivia has a president who can truly claim to be from that nation’s indigenous majority. But these developments have been uneven. Especially in the case of indigenous peoples, access to political power has sometimes further fractured the political system, producing separatists pressures by both indigenous and nonindigenous peoples.

Also disturbing has been the failure of traditional political parties and leaders to exercise effective power once they take office. In many nations, polls indicate that political parties have the lowest or nearly the lowest popular support and credibility of any institution. The greatest threats to democracy often come from within rather than outside the system, from those who proclaim its virtues rather than those who advocate alternative forms of government. As Larry Diamond has observed:

The problem in these states is that bad government is not an aberration or an illness to be cured. It is… a natural condition. For thousands of years, the natural tendency of elites everywhere has been to monopolize power rather than to restrain it—through the development of transparent laws, strong institutions, and market competition. And once they have succeeded in restricting political access, these elites use their consolidated power to limit economic competition so as to generate profits that benefit them rather than society at large. The result is a predatory state.

(Diamond 2008, 43)

Reactions to this take many forms. Some long for a return to the authoritarian regimes of previous decades; others seek to accommodate varying degrees of populism within the democratic spectrum. There are efforts to modify traditional forms of representative government in order to incorporate traditionally excluded or marginalized elements of society. Others see such efforts as being all too easily manipulated by ambitious groups or individuals determined to promote their own agendas. The current situation in Bolivia, Nicaragua, and Venezuela, all of whose governments came to power through elections, exemplifies these issues and makes an examination of the nature and status of hemispheric democracy all the more important.

In summation, Latin American democracy has made significant, but uneven, progress. If the era of military regimes seems ended, other threats remain and, in some cases, seem to be gaining strength. Democracy’s future will depend not just on the conditions within individual nations, but on the ability of the hemisphere as whole to effectively join together in its institutionalization. The United States, for good or for ill, will play a central, though diminished, role in this process, but so will global economic and political trends, increasingly beyond the control of any nation-state. The process will be protracted, the ultimate outcome still uncertain, but the result will be crucial in shaping the lives of everyone in the Americas for the rest of the twenty-first century.

Note

References

Diamond, L. (2008) “The Democratic Rollback.” Foreign Affairs 87(2) (March/April: 36–48).

James, R.R. (ed.) (1974) Winston Churchill: His Complete Speeches, 1897–1963. London: Chelsea House.

Wesson, R. (1982) Democracy in Latin America: Promise and Problems. New York: Praeger Publishers.

![]() Section I

Section I

The State of Latin American Democracy![]()

2

Democratic Consolidation in Latin America?

Jennifer S. Holmes

During a time of economic crisis and adjustment, many Latin American countries transitioned from authoritarian regimes to democratic regimes in the 1980s. This was not the first experience with democracy in the region. Since their independence in the 1820s, many Latin American countries “were in the vanguard of international liberalism when they repudiated monarchism, aristocracy and slavery in the past [nineteenth] century, and at least in theory their governments have long rested on the principle of popular sovereignty” (White-head 1992, 147), although elections consisted of limited competition among elites. The reality was one of mostly oligarchic or co-optative democracies (Skidmore and Smith 1997, 62), which struggled with the negative colonial inheritances of “a hierarchical society based on class and race, and an economy featuring highly unequal distribution of land and wealth” (Handelman 1997, 26). The evolution of Latin American democracies is unique compared to other regions due to four factors: relatively stable borders, pacted democratization, poorly functioning and long-established market economies, and deep inequalities (Whitehead 1992, 157–58). During the twentieth century, Latin American regimes veered from experiments of expanding suffrage to periods of authoritarian rule. By the early 1980s, most of the authoritarian regimes were liberalizing and becoming more democratic. These “new” democracies continue to face fundamental challenges of creating stable and functional democracies, increasing participation, and providing economic opportunities for their citizens. After discussing the general trends of transitions to democracy and democratic consolidation in this chapter, the focus will change to assessing the broad performance and qualities of these new democracies.

The literature on democratic consolidation has been compared to a “terminological Babel” (Armony and Schamis 2005, 114). Existing attempts to assess national development and processes of democratization suffer from conceptual and measurement challenges. Most definitions of democracy focus on procedural aspects such as elections, without taking into account economic development or the capabilities of those institutions to expedite economic and political development of citizens.1

The literature on the definition of democracy is hotly contested. As Kathleen Schwartzman (1998, 161) states, “[T]he debate over the essence of democracy has in no way been resolved in the wave literature.” In terms of conceptualization and measurement, there is a lengthy debate.2 Most studies utilize a definition based upon procedural aspects of democracy and/or political liberties (Collier and Levitsky 1997; Munck and Verkuilen 2002; Bollen and Paxton 2000). This approach is heavily influenced by the work of Robert Dahl (1971) and his seven institutions of polyarchy: elected officials, free and fair elections, inclusive suffrage, the right to run for public office, freedom of expression, existence and availability of alternative information, and associational autonomy.

As Collier and Levitsky (1997) note, among the procedural definitions, the debate revolves around adjectives. They found hundreds of “subtypes” among the different definitions of democracy. Beyond a minimum of free elections, scholars disagree about what additional attributes should be included as part of the minimal standard for democracy (Collier and Levitsky 1997, 433; O’Donnell and Schmitter 1986; Di Palma 1990, 28; Huntington 1991, 9; Przeworski et al. 2000). A drawback of minimalist positions is that they may include authoritarian regimes if they have elections, even if the regimes are not free (Mainwaring, Brinks, and Pérez-Liñán 2001, 41–2). Because of concern over including authoritarian or semi-authoritarian regimes when using a minimalist definition, some advocate including other aspects of procedural democracy, such as civil liberties or an expanded notion of accountability. Without these basic protections, elections can be easily subverted (Mainwaring, Brinks, and Pérez-Liñán, 2001, 43). Scholars such...