The last decade of the twentieth century was marked by waves of migration from the USSR and its successor states. The long list of destinations that absorbed immigrants of Jewish descent from the FSU after the collapse of the empire is headed by Israel with its one million migrants. The “iron curtain” was lifted in 1989 and already in 1990 the United States restricted its immigration procedures for Soviets. In the language of Soviet propaganda, the US immigration bureaucrats “poured water on the mills of Zionist ideology” by turning Israel into the easiest destination to get to for the Soviet emigrants. Even though the process leading to the collapse of the Soviet Union was set in motion already in March 1985 when Gorbachev became the General Secretary of the Communist Party, Israel was unprepared to accommodate the thousands of migrants who started arriving in 1989. For the next five years (1990–1994), monthly immigration flows increased exponentially. The inflow of FSU immigrants grew from about 1500 in October 1989 to about 35,000 in December 1990. Since 1992, the annual immigration rate has never crossed the 100,000 point, but it took ten years for the rate to drop below the 50,000 point.1 In contrast to other immigrant societies, Israel provided immediate access to citizenship to all newcomers entering the country under the regulations of the Law of Return. This act, apart from having practical meaning, symbolizes the tie between the receiving state and its ethnic immigrants.

A. Party Level

The emergence of “Russian” immigrant parties was precipitated by the Zionist Forum—an organization created in 1988 and disintegrated in 2001. The committee of the Forum comprised 105 members; among them were Yuri Stern, Ida Nudel, and Avigdor Lieberman. Initially, the Forum was presented as an apolitical body named by its founders as a “ministry of Aliyah,” an alternative to the Absorption Ministry, which had difficulties adequately integrating immigrants into the Israeli labor market. The forum, led by Natan Sharansky, served as the basis for the creation of the influential immigrant party Israel-be-Aliya (IBA), which explicitly appealed to FSU immigrants, put the interests of immigrants in the center of its electoral campaigns, and used attributes ensuing from ethnic origin as the basis for mobilization (see Gitelman and Goldstein, 2001). Ethnic origin is one of the frequently evoked components of ethnicity (see Chandra, Wilkinson, 2008: 535) along with language, religion, cultural background, and physical appearance (e.g., Fearon, 2003; Horowitz, 1985; Alesina et al., 2003). To facilitate a better understanding of immigrant politics, this chapter draws the difference between the above attributes and organizes them along the lines of ethnic structure and ethnic practice.

Ethnic structure encompasses a narrow list of descent-based attributes (race, place of birth, and religion) that have a property of changing only over the very long term (generations) but being fixed in the short term. Ethnic practice stands for cultural, linguistic, and behavioral categories based on the above attributes that can (though need not necessarily) change during one’s lifetime. It follows that being born in the FSU, Morocco, or Ethiopia, or belonging to a particular religious stream is an attribute related to ethnic structure, while the decision to consume information, cultural products, education, and other services in a particular language is related to behavioral categories that may change in the short term and, thus, belong to the realm of ethnic practices.

Based on the above distinction, an ethnic political party can be defined as a party that represents itself to voters as an agent that acts on behalf of the interests of one or several ethnic groups (that share at least one ethnic structure attribute) to the exclusion of others, and makes such representation central to its strategy of mobilizing voters. A party defined as ethnic in one election need not be classified the same way in others (Chandra, Wilkinson, 2007: 546). This classification is based on parties’ messages that change across elections, thus making the taxonomy time-sensitive.

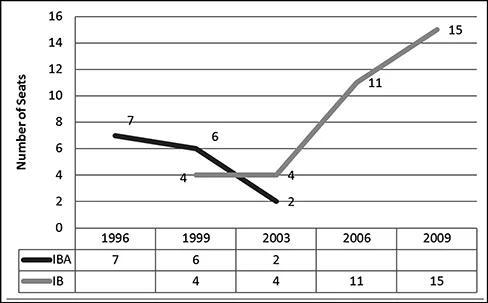

All through its existence, IBA positioned itself as a political body that aimed at addressing the backlog of immigrants’ social and economic problems. Its voters shared an FSU origin—an ethnic structure attribute. In 1996 and 1999, the party enjoyed broad support, which it converted to seven and six seats in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Knessets2, but by 2003 it was abandoned by its supporters, obtained only two seats in the Sixteenth Knesset, and was dissolved into Likud (www.knesset.gov.il) (see Figure 1). Thus, IBA was a de facto ethnic party that mobilized voters on the basis of an ethnic structure component that distinguished this group from the rest of the non-immigrant public.

A catch-all ethnic party is a party that utilizes components of ethnic practice for mobilizing specific groups of voters, but has an explicitly national agenda. It may rely on ethnic practice for attracting voters, but does not place ethnic issues at the center of the campaign. The party makes no explicit appeal to components of the ethnic practice (e.g., Russian culture) and to the attributes of the ethnic structure (i.e., race, religion, origin); the exclusion of others may be implied, but these others are not defined explicitly in ethnic terms.

Both ethnic and catch-all ethnic parties use populist messages to mobilize fluctuating votes. However, the latter have more room to maneuver as they are not restricted to the ethnic subject area, which is central to the mobilizing strategy of ethnic parties.

Ethnic and catch-all ethnic parties differ in several respects. First, ethnic parties formulate their central appeals for popular mobilization on the basis of attributes derived from the ethnic structure. Catch-all ethnic parties may use ethnic practice as a collateral component of mobilization, but no inherent attribute of ethnic structure may be present in their electoral campaign. Second, populist appeals articulated by ethnic parties divide the political map into “us and them.” Catch-all ethnic parties send messages that may imply a division, but they do not explicitly define the ethnic structure attribute of the excluded group. Third, both ethnic and catch-all ethnic parties can act as loyal outsiders who criticize the political establishment through anti-establishment appeals but do not question its legitimacy. However, ethnic parties may also explicitly question the legitimacy of the political establishment. This option of mobilization is absent from the electoral arsenal of catch-all ethnic parties. Fourth, in contrast to ethnic parties, catch-all parties may not limit their appeals to ethnic topics and can address a variety of issues. This allows the harvesting of floating votes from all social strata, ideological camps, or religious denominations.

While Israel-be-Aliya was an ethnic party, I claim that Israel Beitenu—throughout its electoral history, and in particular in 2009—should be defined as a catch-all ethnic party, which represents broad rather than ethnic interests and uses ethnic practice attributes merely as a tool for mobilization. In 1999, IBA lost nationalistically and security oriented votes to Israel Beiteinu, a party formed for the 1999 elections by Lieberman, Nudelman, and Stern (Gitelman and Goldstein, 2001). In 2000, the party joined the National Union—an alliance of right-wing religious parties. In the 2003 elections, the joint list won seven seats, with IB being given four of them. The success of Shinui among the immigrant secular right-wing electorate in 2003 and its subsequent disintegration created a large group of voters who could not have been targeted by IB as part of an alliance with the National Union. In 2006, IB split with the National Union and gained seven additional seats. These seats may have represented secular voters who left Shinui and those who planned to vote for Kadima under the leadership of Ariel Sharon (Philipov, 2008; Shamir et al., 2008). The party continued with its catch-all strategies in 2009 and managed to add another four mandates in the Eighteenth Knesset.

B. Electoral Level

Much has already been written on the socio-demographic (e.g., Remennick, 2003, 2006; Leshem and Lissak, 1999; Horowitz, 1999; Ben Rafael et al., 1996; Lisica and Peres, 2000), cultural (e.g., Ro’i et al., 1996; Al Haj, 2002, 2004), and political (e.g., Gitelman and Goldstein, 2004; Philipov, 2008; Konstantinov, 2008; Peled and Shafir, 2002) characteristics of the new immigrants.

Immediate access to citizenship and the relative share of FSU immigrants in the general population made the existence of the “Russian immigrant sector” highly visible. The intensity and alacrity of immigrants’ political incorporation were conditioned by the popular consensus that assigned a very important role to this type of ethnic immigration, and by the symbolic ties that immigrants felt they had with the dominant political collective. In Israel, the declarative importance of ethnic Jewish immigration is much higher than in other immigrant societies. It is reflected in political behavior developed by the newcomers, who according to the official rhetoric, return “home” rather than immigrate to Israel.

Over time, migrants’ voting behavior pointed to shifting perceived interests, thus indicating an evolving rather than stable nature of the immigrant collective. In 1996 and 1999, ethnic structure related identities (Soviet origin) articulated into mobilization around IBA. Interests related to Israeli socio-political reality, such as resentment with institutionalized religious dogmatism or the desire to advance the settlement of the conflict with Palestinians, translated into support for Israeli non-immigrant parties in 2003 and 2006 and the reversal from ethnic-sectarian politics. In 2003, three parties—Likud, National Union, and the secular, liberal, and right-oriented Shinui—each received approximately one in four votes from the migrants, while IBA ended up with only two parliamentary places (Figure 1). In 2006, the votes of immigrants split between Kadima and Israel Beiteinu. Kadima was a centrist party created by Ariel Sharon, a charismatic and secular leader who was well-advertised in the Russian media. Israel Beiteinu also heavily relied on this media. The unexpected departure of Sharon from the political arena produced a rollback of immigrant votes from Kadima to IB (Philipov, 2008: 139: Figure 2; Shamir et al., 2008).

Figure 1

Seats won by Israel Beiteinu and Israel-be-Aliah, 1996–2009

Source: Based on data taken from the Israeli Knesset official site www.knesset.gov.il

In 2003 IB ran in alliance with the National Union. After wining two seats in 2003 the two IBA MKs joined Likud3.

This work will now focus on the 2009 elections, and will show that a well thought-out electoral campaign of Israel Beiteinu based inter alias on attributes of ethnic practice and astute capitalization on the insecurity conditioned by the military operations in Lebanon in 2006 and in Gaza in 2009 allowed the party to add another four mandates to its Knesset list.