![]()

1

Gathering Information About Students’ Affect: Why Bother?

In 1894 Alfred Binet was commissioned by the French Ministry Of Education to devise a testing instrument that could be used to identify those students who could not benefit from the French educational system because of their “subnormal” intelligence. The instrument that he and Theodore Simon designed became the model for future intelligence tests in particular and cognitive tests in general.

Although most people in education realize Binet’s impact on the field of intelligence testing, few recall much of his thinking at the time he was devising this instrument. Perhaps some examples of this thinking will help the reader understand why a reference to Binet is used to introduce a book dealing with affective characteristics and affective assessment. The following three excerpts are taken from Binet and Simon’s (1916) now classic book, The Development of Intelligence in Children:

Our examination of intelligence cannot take account of all [the] qualities, attention, will, regularity, continuity, docility, and courage which play so important a part in school work, and also in after-life; for life is not so much a conflict of intelligence as a combat of character. (p. 256)

We must expect in fact that the children whom we judge the most intelligent, will not always be those who are the most advanced in their studies. An intelligent pupil may be very lazy. We also notice that the lack of intelligence of certain subnormal pupils does not account for their retardation. We recall what we saw when we followed the lesson for many hours in a subnormal class. It was surprising to see how restless they were, always ready to change their places, to laugh, to whisper, to pay no attention to the teacher. With such instability, it would require double the intelligence of a normal pupil to profit from their lessons. (p. 256)

And now as a pedagogical conclusion, let us say that what… [pupils] should learn first is not the subjects ordinarily taught, however important they may be; they should be given lessons of will, of attention, of discipline; … in a word they must learn how to learn. (p. 257)

These passages reflect some very nonintellectual thoughts for someone who is considered the father of intelligence testing. In these three excerpts, Binet and Simon (1916) clearly stated the predominant role of nonintellectual characteristics in school learning. These characteristics serve two functions. First, they are necessary for successful learning in school. As such, Binet indicated that they should be developed before traditional subject matters are taught. Those students who do not possess these nonintellectual characteristics will have difficulty learning the traditional subject matters, because they would need “double the intelligence of a normal pupil” (to do so. Second, these nonintellectual characteristics are important as end products of schooling because “life is not so much a conflict of intelligence as a combat of characters.” Thus, according to Binet, children’s development of nonintellectual characteristics in the schools is at least as important as the development of intellectual characteristics.

Concerns for noncognitive1 student characteristics continue today. Interestingly, their importance as both means and ends is still recognized. Popham (1994), for example, suggested that:

the reason educators attend to affective variables is because such variables influence students’ future behaviors. Students who have a positive attitude toward learning will be inclined to continue learning after they leave school. Students who have an interest in art will tend to volitionally seek out artistic experiences. Students who value freedom will be more likely to behave in a manner that increases their freedom rather than constrains it. (p. 405)

Similarly, Messick (1979) linked noncognitive characteristics with motivation. “Since a motive is any impulse, emotion, or desire that impels one to action, almost all… noncognitive variables … qualify as motivational to some degree” (p. 285). Among the affective characteristics empirically connected with motivation are locus of control and interest (Messick, 1979), expectancies for success and the value attached to academic success (Berndt & Miller, 1990), and a sense of school belongingness (Goodenow & Grady, 1993).

With respect to affective outcomes of education, there is strong public support. In the United States, a Gallup poll taken in 1994 asked three questions concerning character education. A majority of those polled favored courses on values and ethical behavior (an increase from 1987, the last year this same poll was taken). In addition, more than 90% of those surveyed favored the teaching of core citizenship values. Finally, two thirds favored nondevotional instruction about world religions (Elam, Rose, & Gallup, 1994).

Consistent with these public perceptions, educators have begun to argue for the importance of character education. Some support the need for specific character education programs (Lickona, 1997; Power & Higgins, 1992; Watson, Battistich, & Solomon, 1998). Others argue that character education is, has been, and should be a part of the overall educational program.

A fundamental premise of traditional education has been that every teacher is a teacher of morals. This premise can be construed in two ways: first, that every teacher should be a teacher of morals and, second, that every teacher is—willingly or not—a teacher of morals. It seems to me that both construals are correct. Teachers—even when they deny that they do so—transmit something of moral values and, since this transmission is inevitable, they should seek to do a responsible job of it. (Noddings, 1997, p. 1)

The purpose of this book is to present a conceptualization of the domain of affective characteristics and a discussion of how information about affective characteristics can be collected, analyzed, and interpreted. In writing this book, we hope that concern for affective characteristics will become an integral part of schooling in this country and throughout the world. By using the phrase “integral part” we are conveying our hope that concern for the affective domain will supplement rather than replace the current concern for the cognitive domain. This integration of intellectual and emotional is needed if schools are to fulfill their responsibility for providing high-quality education for all students.

Definitional Concerns

In order to facilitate communication between us and the readers, several terms need to be defined. Three of the most important terms are those in the title of the book; affective characteristics, assessment, and school.

Affective Characteristics

Humans possess a variety of characteristics, that is, attributes or qualities that represent their typical ways of thinking, acting, and feeling in a wide variety of situations. These characteristics often are classified into three major categories. The first category, cognitive characteristics, corresponds with typical ways of thinking. A second category, psychomotor characteristics, corresponds with typical ways of acting. A third and final category, affective characteristics, corresponds with typical ways of feeling. Thus, within this configuration, affective characteristics can be thought of as the feelings and emotions that are characteristic of people, that is, qualities that represent people’s typical ways of feeling or expressing emotion.

Despite this traditional differentiation, it is important to remember that:

few, if any, human reactions fall completely into one of these categories [cognitive, affective, and psychomotor]. It is important that the affective domain be understood to be a construct, not a real thing, and that labeling of certain reactions as affective … is to point out aspects of these reactions which have significant emotional or feeling components. (Tyler, 1973, p. 1)

Messick (1979) echoed these same sentiments when he wrote:

it is clear that simple contrasts such as “cognitive” versus “noncognitive” are popularly embraced in spite of the dangers of stereotyping, probably because they highlight major distinctions worth noting. It is in this spirit, then, that some major features of cognitive and noncognitive assessment are ad- dressed-with an insistence that cognitive does not imply only cognitive and that noncognitive does not imply the absence of cognition. (p. 282)

The word “typical” is important in the definition of affective characteristics. Humans are not computers; their emotions cannot be programmed to be constant. Rather, the emotional states of humans vary from day to day and from situation to situation. Some days people are up emotionally, other days they are down. Some situations are stressful, others are relaxing. Despite this variability, however, people tend to have typical ways of feeling. Some people generally tend to be up, whereas others tend to be down across a variety of days and situations. In order to understand the affective domain, we must focus on these typical feelings and emotions. Such focus is not intended to downplay the variability of these feelings and emotions. Indeed, this variability must be considered if we are to understand the affective realm. Rather, this focus on typical feelings and emotions is meant to provide an understanding of the general way of feeling so that deviations can be noted and understood as well.2

In summary, then, a specific human characteristic must meet two general criteria to be classified as affective. It must involve the feelings or emotions of the person. In addition, it must be typical of the feelings or emotions of the person. Three more specific criteria must be met by all affective characteristics: intensity, direction, and target.

Intensify refers to the degree or strength of the feelings. Some feelings are stronger than others. “Love,” for example tends to be a stronger emotion than “like.” Similarly, some people tend to have stronger feelings than other people. Some people, for example, are extremely tense, others are only moderately tense.

Direction is concerned with the positive or negative orientation of feelings. Put simply, direction has to do with whether a feeling is good or bad. Some seem to be innately good or bad: Pain is bad, and pleasure is good. Others are considered good or bad depending on their definitions within particular cultures. In U.S. culture, for example, enjoying school is thought of as a positive feeling, whereas anxiety usually takes on a negative connotation. Most positive feelings have negative counterparts and vice versa. Hating school is the negative counterpart of truly enjoying school. Similarly, being relaxed is the positive counterpart of being tense.

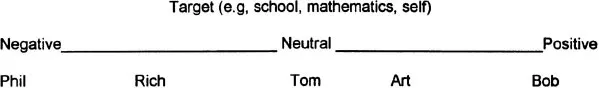

When both intensity and direction of feelings are considered, it becomes apparent that most affective characteristics exist along a continuum. The midpoint of the continuum differentiates the positive from the negative direction, whereas the distance from the midpoint indicates the intensity of the feelings. A graphical representation of a continuum of feelings is displayed in Fig. 1.1.

Fig. 1.1 An illustration of the continuum of feelings.

Five boys’ names have been written along the continuum: Phil, Rich, Tom, Art, and Bob. As can be seen, these boys differ from one another in the intensity of their feelings, the direction of their feelings, or both. Phil and Bob have equally intense feelings, but the feelings differ in direction. The same is true of Rich and Art. In contrast, Art’s feelings and Bob’s feelings lie in the same direction but differ in intensity; so do Phil’s feelings and Rich’s feelings. Finally, Tom’s feelings have neither direction nor intensity. One may say they are neutral.

The third specific critical feature of affective characteristics can be termed the target. Target refers to the object, activity, or idea toward which the feeling is directed. If, for example, anxiety is the affective characteristic under consideration, several targets are possible. A person may be reacting to school, mathematics, social situations, or teachers. Each can be a target of the anxiety. Once identified, the name of the target can be placed above the affective characteristic continuum as shown in Fig. 1.1.

Sometimes the target is known by the person, sometimes it is not. That is, a person may begin to feel tense when a test is distributed in class. This person is likely to be aware that the target of the tenseness is the test. Another person, on the other hand, may be sitting in his or her living room and suddenly begin to feel tense. This person might wonder, “Why am 1 tense?” Perhaps some fleeting thought triggered the tension, a thought that cannot be recalled. In this case the target is not consciously known. This latter type is referred to as free-floating anxiety.

Sometimes the target is implicit in the stated affective characteristic. For example, the target of self-esteem is obviously “the self.” In other cases, the target is connected to the affective characteristics (e.g., attitude toward mathematics, interest in learning science). In these situations, the affective assessment instruments tap what might be termed affect-target combinations. That is, it is not general attitude that is assessed (an affective characteristic); rather, it is attitude toward mathematics (an affect-target combination).

In sum then, affective characteristics possess five defining features. Two are general, and three are specific. First, they are feelings or emotions. This feature differentiates affective from other human characteristics. Second, they are typical ways of feeling. This feature differentiates affective characteristics from affective reactions induced in certain situations. Third, they possess some degree of intensity. Fourth, they imply direction. Fifth, there is some target (either known or unknown, implicit or explicit) toward which the feelings are directed.

Assessment

Let us turn now to a consideration of the term assessment. As used in this text, to assess a human characteristic simply means to gather meaningful information about that characteristic. Such information permits one to determine whether a person possesses a particular characteristic or how much of a particular characteristic a person possesses. For example, the information can tell us whether Cathy is anxious about taking tests (Does Cathy possess test anxiety?), or it can tell us how anxious Cathy is about taking tests (How much test anxiety does Cathy possess?). In the first instance, the information is seen as dichotomous (that is, she does or she doesn’t). In the second it is seen as continuous (that is, she does to varying degrees). Both types of information are useful in certain situations and for certain purposes.

This last statement leads to an important aspect of educational assessment in general and of affective assessment in particular. Assessments are usually made for some reason. That is, there generally is some purpose for which information is gathered. A teacher, for example, may gather information about his or her students’ interests in a particular topic for the purpose of deciding whether or not to include the topic in the curriculum. A principal may be interested in gathering information about a prospective teacher’s educational values for the purpose of seeing whether the prospective teacher’s values are consistent with those of the present staff, the current philosophy of the school, or both. Whatever the reason for making the assessment, it should be clearly stated before the information is gathered. (More is said about the purposes of affective assessment in chap. 5, this volume.)

We now arrive at an important distinction between assessment and evaluation. As we suggested, assessment refers to the gathering of information about affective characteristics. Evaluation, on the other hand, refers to either a judgment of the worth or value of the characteristics per se or the worth or value of the amount of the characteristic actually possessed by a particular individual. Thus, whereas assessment tells you what affective characteristics a person possesses (e.g., what educational values does this teacher hold?), evaluation considers the worth or value of these characteristics (e.g., does this teacher hold the right values?). Likewise, whereas assessment tells how much of a particular characteristic a person possesses (e.g., how much interest in a particular topic do students have?), evaluation makes a value judgment regarding that amount of that characteristic (e.g., is that sufficient interest to include the topic in the curriculum?).

One final point must be made ab...