![]()

Part I

A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF APPROACHES TO SELF AND IDENTITY

![]()

Chapter 1

Identity Theory in Perspective

For most of human history, forming an adult identity was by all accounts a relatively straightforward process. The average person simply assumed and fitted into the culturally prescribed roles that his or her parents and grandparents had themselves adopted. Those who did not do so might have been banished from their community, or at least sanctioned in some way. Of course, those in positions of authority and power may have had more choice in the latitude of their identities than others, but even their options were limited by restrictive social customs and the narrow range of roles available in the rudimentary economies.

This situation was characteristic of premodern societies that spanned the period of human evolution from simple tribal through feudal social organizations. Given their importance for human evolution and social adaptation, these forms of society are crucial reference points or baselines from which we can understand emergent identity problems associated with contemporary late modern societies. As humans have attempted to adapt to modern and late modern forms of social organization, where choice has replaced obligation as the basis of self-definition, identity formation has become a more difficult, precarious, and solitary process for which many people are unprepared in terms of their phylogenetic background.

For most of human history, identity formation was not a matter of individual choice and negotiation, so problems associated with these activities were not common. Accordingly, in this historical sense, humans have not been accustomed to living in societies where they are continually confronted with high levels of choice over fundamental matters of personal meaning. It is in this context that we can understand how humans living in late modern societies are still attempting to learn how to deal with this challenge. In other words, the process of forming an adult identity has become dramatically different for most people in Western societies, and many people have not developed the means for coping with a process that allows them to make choices, the consequences of which they may have to live with for the remainder of their lives.

Although many people welcome the ability to choose, they may not be so happy with having to assume the responsibility for the outcome of those choices (note the widespread avoidance of taking responsibility for one’s actions). Available social models of adult identities do not always help those coming of age because many such models are ambiguous or their relevance becomes quickly outdated (Côté, 2000). In fact, difficulties with identity formation processes are so widespread they are now being considered “normal” in many respects. These normal difficulties include people being: unsure about what they believe in; uncommitted to any course of future action; open to influence and manipulation; and unaware that they should pass a sense of meaning on to their children. In all of these cases, people lack a sense of self-definition rooted in a community of others, which was the basis of human identity throughout history. Moreover, even forms of identity formation that can be considered “pathological” may not be recognized as seriously harmful to the person or community. For example, the American Psychiatric Association at one time recognized a general “Identity Disorder,” but subsequently redefined it as “Identity Problem” (cf. the DSM-III and the DSM-IV). We are just beginning to understand personality problems such as the Borderline Personality Disorder and the Dissociative Identity Disorder, but these are often tolerated in communities and/or misdiagnosed when a person seeks medical assistance. It will clearly take some time before we come to grips with the nature of identity formation and the important issues associated with it. We hope this book is a step in the right direction.

Our point here is not to glorify premodern societies, but rather to use them as a point of comparison for understanding identity problems. Indeed, premodern societies had their own problems, including widespread poverty, short life spans, uncontrollable epidemics, poor medical knowledge, and the like. Clearly, we are not calling for a return to premodern societies, nor are we saying that late modern societies are all bad. However, as humans have solved certain problems of survival with technological advancements, new unanticipated problems associated with the meaning of existence have emerged, including how to deal with the greater latitude of choice that life-sustaining technology has given us. The issue of how to deal with technological advancements in terms of a set of humanistic ethics weighed heavily on Erik Erikson, and his deliberations of this thorny issue can be found in many of his writings.

SOME TYPICAL IDENTITY FORMATION STRATEGIES IN LATE MODERNITY

In order to more concretely illustrate how the task of identity formation has changed, and the “normal” problems now associated with it, we introduce here a tentative “working typology” of five identity strategies that seem to capture the range of contemporary life-course trajectories. For heuristic purposes, we have named these strategies as follows: Refusers, Drifters, Searchers, Guardians, and Resolvers (cf. Josselson, 1996; Klapp, 1969). This typology is based on a synthesis of the identity formation literature and will be elaborated on in chapter 4 after we review this literature. We offer this typology here to illustrate the following: (a) historically speaking, there are now a greater number of ways in which “adult” identities are formed; (b) adult identity formation can be rather chaotic; and (c) for virtually everyone, this process now involves an individualized “strategy” that may be carefully and consciously planned or may be part of a continual struggle with one’s inner conflicts and resources, or lack thereof.

Refusers typically develop a series of defenses with which to “refuse” entry into adulthood. These include a series of self-defeating cognitive schema that lock them into child-like behavior patterns characterized by a dependency on someone or something else. They may remain with their parents well into their 30s (or for their lives); they may refuse to acquire occupational skills, and thus remain dependent on government benefits, the proceeds of crime, or an underground economy; or they may find a mate or a group of friends that enables them to stay perpetually in a preadult status. In terms of their character formation, Refusers were likely given little structure and encouragement as children regarding engagements with their social environments, and as adolescents they were likely given little guidance regarding ways in which they could develop themselves intellectually, emotionally, or vocationally (cf. the literature on permissive parenting; Steinberg, 2000). Thus, Refusers have few personal resources with which to actively engage a community of adults. In what should be their adult years (their 20s and 30s), they engage in a number of behaviors that sabotage their standing in any adult community. For example, they may engage in heavy drug or alcohol use; they may not maintain steady employment even when there may be no barriers to this; and they may periodically act out in immature ways (e.g., temper tantrums). Of course, Refusers could likely have been found in communities throughout Western history (cf. Erikson’s, 1968, concept of the negative identity), but our contention is that this way of handling the demands of adult identity formation is increasing in late modernity (Côté, 2000). This type of person seems most likely to take refuge in one of the many youth street gangs now proliferating in urban centers, or in a drug-oriented youth culture, rather than to confront the task of taking on adulthood responsibilities and/or attempting to overcome socioeconomic obstacles through legitimate means.

Although Drifters are similar to Refusers in their lack of integration into a community, they do have more personal resources at their disposal. These resources could include higher levels of intelligence, family wealth, or occupational skills, yet the Drifter seems unable or uninterested in applying these resources in a consistent and continuous manner. The Drifter may feel that conforming may be a “cop out,” or may be “selling out;” or the Drifter may simply feel that he or she is “too good” to “toe the line.” Whatever the reason, the effect is more or less the same: a chronic “preadult” behavior pattern characterized by poor impulse control, shallow interpersonal relationships, and little in the way of commitments to an adult community. This way of handling the demands of adult identity formation also seems to be increasing in late modernity (cf. Goossens & Phinney, 1996; Marcia, 1989a).

The Searcher, in contrast to the previous two strategies, has not given up on finding a validating adult community; instead, the Searcher cannot seem to find a community that satisfies his or her often unrealistically high criteria of functioning. Searchers are habitually driven by a sense of dissatisfaction with themselves and this dissatisfaction can be projected onto others. Unable to find perfection in themselves, and unable to find perfection in a community, the Searchers are locked into a perpetual journey for which there can be no end. They may have sought out role models who have claimed perfection, but when these models are found to be imperfect, the Searchers may grow tired of them. Or, the Searcher’s own imperfections—in contrast to those of the role model—may create a sense of despair that drives the Searcher to look elsewhere.

The Guardian, in contrast to those three strategies, has likely experienced a well-structured childhood in which the values of the parent and/or community have been thoroughly internalized. This structure gives the Guardian a set of personal resources with which to actively engage the adolescent environment and move fairly quickly into adulthood. However, this internalized structure can be impervious to influence and change, leaving the person vulnerable in several ways. First, the person can neglect to undergo certain developmental experiences that help him or her to grow emotionally or intellectually. Second, the person can over-identify with the parent, making it difficult for him or her to individuate as an adult (cf. the literature on authoritarian parenting; Steinberg, 2000). And, third, as an adult, the person may be unduly rigid in terms of his or her own self-development and relations with others. In late modernity, change is a fact of life and a large variety of lifestyles and opinions will be encountered; to deal with these in a rigid manner can lead to all sorts of hardship for oneself and for others (cf. Josselson, 1996). Traditional, premodern societies generally prescribe this identity strategy among their members, whereas the three strategies discussed earlier can be seen as anomic consequences of the disjunctive socialization process that are becoming increasingly common in late modern societies.

Finally, the Resolver actively engages himself or herself in the process of forming an adult identity, taking advantage of the opportunities in late modern societies in spite of the anomic character of these types of societies. This strategy involves actively developing one’s intellect, emotional maturity, and vocational skills rooted in one’s general competencies and interests. It also involves learning about the world and going out in the world to actualize one’s budding abilities. Of course, many people have the potential to be Resolvers but find themselves held back for one reason or another (e.g., various commitments, like having a child, or having parents who are unable to invest in their education). However, even within these constraints, a certain amount of active engagement is usually possible; in fact, unless one is pulled by the processes that are felt by, say, Refusers or Guardians, attempting this strategy in some way may be unavoidable in late modern society, which actively stimulates this form of identity formation in certain ways (e.g., educational systems in which large proportions of populations participate well into the tertiary levels). Whatever the circumstances, those who are disposed to this identity strategy will find themselves yearning to grow in certain ways and will likely do so with whatever means are at their disposal. The impetus for this strategy is likely rooted in an internalized childhood cognitive structure and made possible during the transition to adulthood by a conducive motivational mindset associated with a desire to reach one’s potential (cf. Côté & Levine, 1992, and the literature on authoritative parenting; Steinberg, 2000).

Sociological factors like social class, gender, and ethnicity are not necessarily relevant to our understanding of the nature of these identity strategies, although empirical analyses may show different proportions of them in different demographic categories. For example, a Drifter can come from a wealthy background, be a woman, and a minority group member. Similarly, a Resolver could be a minority woman from a working-class background. Our point is that identity formation in late modernity is not as restricted by social ascription as it was in premodern society. Indeed, active identity formation strategies such as those of the Resolver seem to be key if a person is to either overcome socioeconomic obstacles and become upwardly mobile or maintain the high social status of his or her parents. In other words, simply having wealthy parents, or being from an upper class, no longer guarantees that one’s adulthood status reproduces that of one’s parents. However, it appears that Refusers, Drifters, and Searchers seem most likely to experience downward mobility, whereas Resolvers and Guardians seem most likely to experience upward mobility and/or replicate the social status of their parents (see the individualization process, chapter 4).

As we can see from the preceding paragraphs, regardless of the identity strategy undertaken, the citizen of late modern societies will likely encounter continual problems in the formation of an adult social identity and in the maintenance of that identity once it is formed. Moreover, social identities are becoming increasingly transitory and unstable in late modern society (e.g., it is estimated that the current generation coming of age will experience up to six career changes during adulthood; Foot, 1996). Even those social identities that are maintained throughout adulthood will require a certain amount of management in order to sustain validation for them from others. For instance, the person will have to ensure that proper images are created and recreated in interaction with significant others. This form of identity management seems to apply to roles as common as parenthood (e.g., being “fit” or being “good” in terms of shifting standards of child care, like discipline techniques) and as specific as one’s occupational specialization (e.g., being “marketable,” “selling oneself,” and being “non-redundant”). In short, under increasingly anomic social conditions and diminishing consensus regarding traditional and contemporary norms, the formation and maintenance of an adult identity can be problematic for all citizens of late modern societies. Indeed, there is ample reason to believe that this situation is worsening for many people (Côté, 2000).

A FRAMEWORK FOR STUDYING IDENTITY FORMATION, AGENCY, AND CULTURE

The framework we adopt in this book stems from the social psychological tradition in sociology called the “personality and social structure perspective” (House, 1977). House argued that as a field of study, social psychology actually has “three faces.” Only one of the faces corresponds with most people’s conception of “social psychology,” namely, the version found in mainstream psychology departments, which he called Psychological Social Psychology. However, House identified two social psychological traditions in sociology that constitute the other two faces: symbolic interactionism (SI) and the personality and social structure perspective (PSSP).

The PSSP seems most suitable to the task of developing a comprehensive understanding of identity for several reasons, foremost of which is its explicit recognition of the relevance of three levels of analysis. In fact, from the personality and social structure perspective, a comprehensive theory of human behavior requires that these three levels, and their interrelations, be identified and analyzed. In our case, we are specifically interested in a comprehensive theory of human identity formation.

The three levels of analysis inherent to the PSSP are: personality, interaction, and social structure. From this perspective, the level of personality involves the intrapsychic domain of human functioning traditionally studied by developmental psychologists and psychoanalysts, and is referred to variously as the psyche, the self, cognitive structure, and so forth, depending on the school of thought. The level of interaction refers to the concrete patterns of behavior that characterize day-to-day contacts among people in families, schools, and so on, typically studied by symbolic interactionists. Sociologists often refer to this as the micro level of analysis. Finally, the social structural level refers to the political and economic systems, along with their subsystems, that define the normative structure of a society. This last level of analysis is most commonly referred to as the macro-sociological level of analysis.

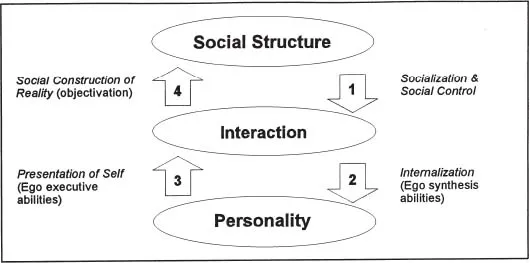

FIG. 1.1. The Personality and Social Structure Perspective (PSSP) model: Three levels of analysis constituting social behavior.

We introduce Fig. 1.1 here to help readers gain an initial grasp of the PSSP. Figure 1.1 illustrates the three levels of analysis along with their interrelationships, which are signified with a series of four arrows representing the continual iterative flow of influence among the three levels. The influence of social structure on day-to-day interactional processes involves socialization and social control processes represented by arrow 1. Arrow 2 is meant to show how exposure to day-to-day interaction with others culminates in the internalization of social structural norms and values, as mediated by the person’s ego synthetic abilities, while arrow 3 illustrates the person’s ego executive abilities in producing self-presentations (the ego and its abilities are discussed in chapter 6). Finally, the person engages in daily interactions with others (arrow 4), an important consequence of which is the social construction of reality, and what Berger and Luckmann (1966) called “objectivation” (see the glossary). ...