1

A Moving Target:

The Illusive Definition of Culture

John R. Baldwin

Illinois State University

Sandra L. Faulkner

Syracuse University

Michael L. Hecht

The Pennsylvania State University

Culture is something that Western societies have not clearly understood, so that the challenges they have to face in an increasingly multicultural world are particularly difficult to manage. Understanding culture is certainly not only a Western problem, but a universal problem as well. (Montovani, 2000, p. 1)1

As we move into the 21st century, it sometimes feels as though we are barreling into a great valley—it is green and lush, but shadowed with uncertainty. It is a valley of mixed hues, fragrances, and textures, and we do not always know whether we should celebrate the diversity of its parts or stop at the edge and admire the whole picture, seeing how the diverse parts work together. Like the description of this picture, we often see diversity and unity in opposition to each other, when in fact, they exist in dynamic balance, each requiring the other.

Issues of cultural unity, diversity, and divisiveness abound as we write this chapter. In the United States, hate crimes are more common than one would like, hate groups are very active, and debates exist about school mascots and the Confederate flag. Worldwide, cultural issues of genocide, government oppression, and terrorism, often rooted in culture and identity, consume people’s everyday existence. At the same time, culture exists at the center of many scholarly disputes and at the forefront of many theoretical advances. It is, as the Encyclopedia of Social and Cultural Anthropology (Barnard & Spencer, 1996) states: “the single most central concept in twentieth-century anthropology” (p. 136), and its influence is now felt across the social sciences.

Interestingly, when we introduce the notion of “culture,” as a variable to explain some behavior, as a topic of academic discussion, or as a concept to help solve everyday problems, we reflect different voices as we use the word. It would be easy enough to say that each of us speaks from her or his disciplinary culture, but even within disciplines, definitions proliferate. One writer complained that although it still is important to study the similar symbols and expectations that give rise to meaningful activity among a group, the actual term “culture” “has so many definitions and facets that any overlap in this myriad of definitions might actually be absent” (Yengoyan, 1989, p. 3). This critique is not new. As early as 1945, Clyde Kluckhohn and William Kelly framed the dilemma in terms of a dialogue between a lawyer, a historian, an economist, a philosopher, a psychologist, a business professional, and three anthropologists, each defining culture different ways. More recently, at the 1994 meeting of the American Anthropological Association, anthropologists urged that the definition of culture be reevaluated considering the multidisciplinary nature of the concept’s usage and the inadequacy of historical approaches (Winkler, 1994).

This debate surrounding the usage of the term “culture” suggests that the term is a sign, an empty vessel waiting for people—both academicians and everyday communicators—to fill it with meaning. But, as a sign in the traditional semiotic sense, the connection between the signifier (the word “culture”) and the signified (what it represents) shifts, making culture a moving target. No one questions that there are multitudinous definitions of culture. In fact, in a classic work on the subject, A. L. Kroeber and Clyde Kluckhohn (1952) collected some 150 definitions of the term and offered a critical summary, which has become the foundation upon which many writers from different disciplines have built their common understandings of culture. At the same time, much has transpired in the academic world during the 50 plus years since that publication.

In this chapter, following a semiotic metaphor, we provide a diachronic (or historical) analysis, observing how culture as a sign has changed through times in the writings of various disciplines. In the next chapter, our analysis is more synchronic (thematic or conceptual), looking across definitions for common themes (Berger, 1998). In this sense, we are following the tradition of Kroeber and Kluckhohn (1952). However, whereas their analysis looked more in detail at each definition within the themes, we discuss themes using exemplars.

“CULTIVATING” AN UNDERSTANDING

OF THE WORD—A HISTORICAL LOOK

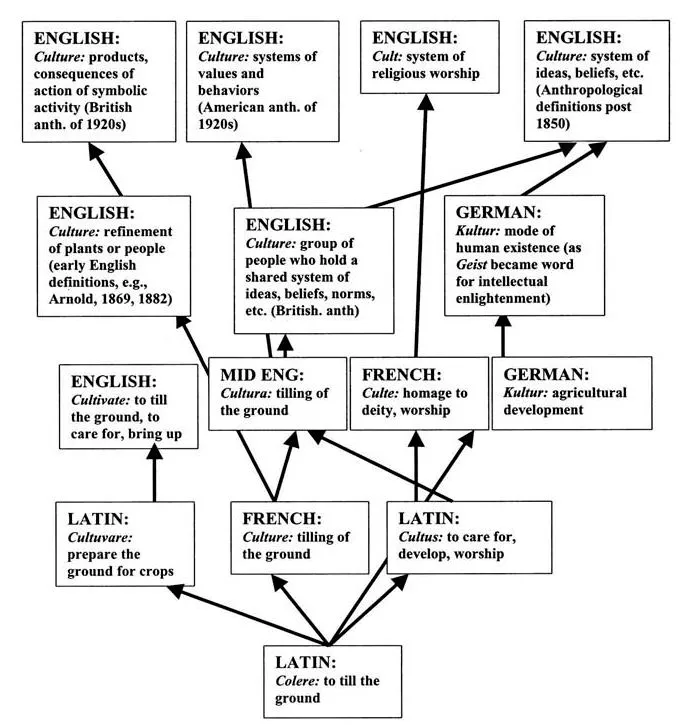

Tracing the various etymologies of culture in a standard dictionary (e.g., Jewell and Abate’s New Oxford American Dictionary, 2001), we can develop the “tree” of meaning shown in Fig. 1.1. In this figure, we can see the original roots of “culture” joined to the histories of “cult” and “cultivate.” The word comes to Middle English (“a cultivated piece of land”) through French “culture,” and that from the Latin verb culturare (“to cultivate,” p. 416). There is a kinship among the words. Cultus, for example (from which we get “cult”) refers to religious worship, which might be seen as a way of bringing up (“cultivating”) someone in a religious group. All versions of the word ultimately come from early Latin, colere, which means to till or cultivate the ground. Several authors outline the etymologic roots of the word, for example Kroeber and Kluckhohn (1952).

FIG. 1.1. Derivation of English word culture and its etymological cousins. Based on Bauman(1973); Jewell & Abate (New Oxford Dictionary, 2001), Kroeber & Kluckhohn (1952); Moore (1997); and Williams (1983).

RaymondWilliams (1983) traced the contemporary word to the German Kultur, which refers to agricultural development. This yields, Williams suggested, three broad categories of usage in the history of the word. The first refers to the “cultivation” of individuals and groups of people in terms of the “general process of intellectual, spiritual, and aesthetic development,” a usage beginning in the 18th century (p. 90). The other uses, each more contemporary, include a “particular way of life, whether of a people, a period, a group, or humanity in general” and “the works and practices of intellectual and especially artistic activity” (p. 90). This last meaning, Williams contended, is the most widely used, and relates to literature, art, music, sculpture, theater, and other art forms.

Kroeber and Kluckhohn (1952) saw the term as first (in the 1700s) signifying a sort of general history. A second strain of meaning, running from Kant to Hegel (late 1700s to early 1800s), aligns the meaning with “enlightenment culture and improvement culture” (p. 23), a notion that gave way to the word “spirit” (Geist) as it moved away from the word “culture.” The third and, for Kroeber and Kluckhohn, current strain, developing after 1850, treats culture as “the characteristic mode of human existence” (p. 27). The authors argued that the Germanic usage of the term later became the conceptualization that anthropologists adopted.

In England, one of the earliest definitions of culture (Matthew Arnold in 1869) was “a pursuit of total perfection by means of getting to know … the best which has been thought and said in the world” (Kroeber & Kluckhohn, 1952, p. 29). Sumner, a well-known anthropologist, criticized this use as “an illustration of the degeneracy of language … stolen by the dilettanti and made to stand for their own favorite forms and amounts of attainments” (Kroeber & Kluckhohn, 1952, p. 29). This reflects a different strain of definition, concomitant with the German view of Kultur, which focused on refinement and the associated expression of “fine arts.” Notably, writers from Sumner on have resisted this notion of culture.

The Encyclopedia of Social and Cultural Anthropology (Barnard & Spencer, 1996) provides a similar picture, presenting two competing strains of the definition for culture. One follows Arnold’s aforementioned definition (1882/1971), treating culture as an abstract concept, something that “everyone had, but which some people had more or less of,” and equating it with civilization (p. 138). This view of culture appears as early as the 17th century in the works of writers such as Francis Bacon, who treated culture as the manners and knowledge that an individual obtains (Bolaffi, Bracalenti, Braham, & Gindro, 2003). The other strain begins with German romanticists, such as Herder, but especially finds voice in Franz Boas and his followers. Boas was one of the first to treat culture in the plural, that is, to speak of “cultures” as groups of people (Bolaffi et al., 2003), although this usage goes back as far as Herder in 1776 (Barnard & Spencer, 1996).

Kroeber and Kluckhohn: A Klassic Kase of Kulture

Kluckhohn’s (1949) early writing on culture foreshadows William’s (1983) definition noted earlier. Kluckhohn (1949) concluded that culture refers to “the total way of life of a people” (p. 17), “a way of thinking and believing” (p. 23), and a “storehouse of pooled learning” (p. 24). Kluckhohn stated that a distinction needed to be made between people who shared a social space and mutual interaction, but not a way of life. This group of people, Kluckhohn called “society,” which he distinguished from those sharing a way of life, which he labeled a “culture.”2 This hints at a deeper tension between the nexus of the terms “culture,” “civilization,” and “society” that has rifted through the social sciences.

Most authors in our list of definitions treat culture as some set of elements shared by people who have a social structure, with the latter referred to as “society.” Robert Winthrop (1991) echoed this distinction. “Culture,” he noted, “focuses attention on the products of social life (what individuals think and do),” whereas social structure (the equivalent of society for Winthrop) “stresses social life as such: individuals in their relations to others” (p. 261). He delineated three definitions of civilization historically used in social science, each with a different relationship to culture: (a) civilization as the “more technical and scientific” aspect of culture, (b) civilizations as “a subclass of world cultures … characterized by complex systems of social inequality and state-level politics,” and (c) the “least useful” relationship, culture as equal to society (p. 34). Edward Tylor’s (1871) definition serves as example of this last relationship between the terms. In summary, despite the relationship of culture to society or civilization, each culture serves to provide an orientation toward the world and its problems, such as suffering and death. In addition, “every culture is designed to perpetuate the group and its solidarity, to meet the demands for an orderly way of life and for satisfaction of biological needs” (Kluckhohn, 1949, pp. 24–25).

Kroeber and Kluckhohn devote most of their 1952 book to a critical review of definitions. They divide definitions into six groups, as follows:

- Enumeratively descriptive (a list of the content of culture)

- Historical (emphasis on social heritage, tradition)

- Normative (focus on ideals or ideals plus behavior)

- Psychological (learning, habit, adjustment, problem-solving device)

- Structural (focus on the pattern or organization of culture)

- Genetic (symbols, ideas, artifacts)

After each set of definitions, they provide commentary, looking at the nuances of similarity and difference between the items under each category. The elements of definition focus on different aspects of culture: There is a set of elements, such as ideas, behavior, and so on (#1) inherited or passed on among a group of people (#2). These elements exist within a connected pattern (#5), meeting purposes or solving problems for the group of people and making up part of the cultural learning (#4) of the behavior prescriptions and values that guide people in knowing how to act in different cultural situations (#3). Genetic definitions (#6) focus on the “genesis” or origins of culture. Such definitions address the questions: “How has culture come to be? What are the factors that have made culture possible or caused it to come into existence? Other properties of culture are often mentioned, but the stress is upon the genetic side” (p. 65; see Berry, 2004, for a concise summary of Kroeber and Kluckhohn’s six dimensions).

We can understand these categories both as aspects of definitions or, to the extent that certain definitions privilege one component over another, as types of definitions. Kroeber and Kluckhohn (1952) admitted close relationships between some categories. For example, genetic definitions differ subtly from historical definitions: A genetic definition “centers on tradition or heritage, but it emphasizes the result or product instead of the transmitting process” (p. 65). A historical definition, on the other hand, emphasizes how traditions are inherited and accumulated over time, with the focus on the passing down of culture, more than simply on a set of elements or patterns of a culture. In addition, each type of definition might have subcategories. Thus, genetic subcategories include an emphasis on products (Kroeber and Kluckhohn’s F1), on ideas (F-II) and on symbols (F-III). Interestingly, a definition that focused on symbols was the “farthest out on the frontier of cultural theory” at the time (p. 69).

Kroeber and Kluckhohn (1952) synthesized the aspects or types of definition into a single, complete, and useful definition:

Culture consists of patterns, explicit and implicit, of and for behavior acquired and transmitted by symbols, constituting the distinctive achievements of human groups, including their embodiments in artifacts; the essential core of culture consists of traditional (i.e., historically derived and selected) ideas and especially their attached values; culture systems may, on the one hand, be considered as products of action, on the other as conditioning elements of further action. (p. 181)

Following in the Footsteps: Traditional Definitions

in the Social Sciences

Many contemporary writers across disciplines either cite or reflect Kroeber and Kluckhohn’s (1952) summary definition, and of course their definition reflects much of what authors, especially anthropologists, have written about the term. Specifically, authors from Stuart Williams (1981) to Edward T. Hall and Mildred Hall (1989)—the former a literary studies/critical theorist and the latter traditional anthropologists—have stressed the systemic element of the definition, following in the footsteps of the early anthropologists such as Edward B. Tylor (1871) and Ruth Benedict (1934/1959). From a systems perspective, anything that operates as a system equals culture. Tylor (1871) for example, saw culture as “that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society” (p. 1). For Benedict (1934/1959) culture denoted “a more or less consistent pattern of thought and action” tied to the “emotional and intellectual mainsprings of that society” (p. 46).

Another way of seeing this system is to view...