![]()

Part I

The Bad Application of Good Science?

![]()

1

Sustainability and Sustainability Indicators

Introduction and objectives

Few development interventions or research initiatives these days can successfully attract funding unless the words ‘sustainability’ or ‘sustainable’ appear somewhere in the proposal to the funding agency. Indeed, if one listens to speeches by politicians or reads articles by economists, policy-makers or scientists, the word sustainable appears with remarkable regularity:

Sustainable development has become the watchword for international aid agencies, the jargon of development planners, the theme of conferences and learned papers, and the slogan of developmental and environmental activists. (Lele, 1991)

Although some have questioned the motives behind this popularity (Bawden, 1997), there is no doubt that sustainable development is now a very dominant theme. Some even go so far as to say that ‘everyone agrees that sustainability is a good thing’ (Allen and Hoekstra, 1992), although to Fortune and Hughes (1997) ‘it [sustainability] is an empty concept, lacking firm substance and containing embedded ideological positions that are, under the best interpretation, condescending and paternalistic’. The main catalyst for this popularity in recent years, particularly in terms of sustainable development, was the Rio de Janeiro Earth Summit held in 1992. The Rio Summit agreed a set of action points for sustainable development, collectively referred to as Agenda 21 (agenda for the 21st century), and governments that signed up to these have committed themselves to action. In order to help put these points into practice, the summit established a mandate for the United Nations to establish a set of ‘indicators of sustainable development’ that will help to monitor progress. In fact, the idea of using indicators as a means of gauging sustainability has become extremely popular, with many governments and agencies devoting substantial resources to indicator development and testing (Hak et al, 2007). Even the idea of a sustainable city, an apparent contradiction in terms, has become so popular that prizes are now provided for those cities deemed to be the most sustainable, and indicators play a major role in this process. The central idea behind the use of such indicators is very simple, and essentially they are designed to answer the question: ‘How might I know objectively whether things are getting better or getting worse?’ (Lawrence, 1997).

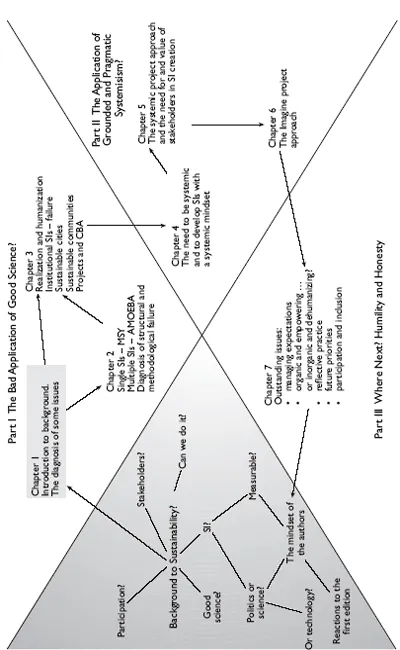

Figure C.1 Chapter 1 in context

Sustainable development is an example of a paradigm quite distinct from what some see as the contradictory term of sustainable growth (see Daly and Townsend, 1992, for a discussion). Paradigms are important in that they are philosophical and theoretical frameworks within which we derive theories, laws and generalizations. In its broadest sense, the sustainable component of the sustainable development paradigm implies that whatever is done now does not harm future generations – a concept often paraphrased as ‘don't cheat on your kids’. However, the precise meaning of sustainable, and what it embraces, varies depending upon who is using it and in what context, a critical point which we return to later. For example, can we sustain our environment within sustainable development, yet ‘cheat our kids’ on other aspects, such as decline in economic performance or worsening social conditions? Sustainable development has, indeed, become a quintessential example of practical holism, but at the same time embodies an ultimate practicality since it is literally meaningless unless we can ‘do’ it. As such, it is firmly rooted in the present.

This book is all about the ‘doing’ of sustainable development. In these pages the reader will frequently come across a liberal sprinkling of terms such as ‘achieve’, ‘implement’, ‘practice’, ‘goal’ and ‘do’ with regard to sustainable development. This reflects an important shift away from ‘sustainable’ as an appealing though rhetorical adjective to ‘sustainable’ becoming both a descriptor of something and a target to achieve. Indeed, since it is the ‘sustainable’ part of sustainable development which particularly interests us, we have tended to refer to ‘sustainability’ in a generic sense, and our discussions of sustainability could be employed to anything that has sustainable as an adjective. Therefore, the same broad points we make apply to sustainable agriculture, sustainable coastal zones, sustainable cities, sustainable communities, and sustainable organizations and institutions – for this reason we have ranged freely between all these domains. The latter two, in particular, will form the focus for Chapter 3. This may appear to be rather cavalier; but ‘sustainable’ in each case refers to much the same, although the detail can be quite different. Taking sustainability in a broad sense allows us to compare and contrast facets of application across these domains, and to apply lessons from one arena to another.

In order to provide the reader with some background, we have begun this chapter with a discussion of a few of the current visions of sustainability, with a particular emphasis on sustainable development. There is, of course, an additional and substantial literature on the meaning of development; but this will not be covered here (see Potter et al, 2003, for a summary).The aim will be to use these visions of sustainability to illustrate some of the difficulties inherent within its concept, and how some people have tried to address these.

As described above, many individuals have noted the need for measuring sustainability, and this chapter will discuss a few approaches in this direction and the problems that people have faced. Again we cannot claim to be exhaustive; but the examples we have chosen illustrate the broad range of approaches with their associated advantages and disadvantages. In particular, the background to the use of indicators as a means of gauging sustainability will be discussed. Chapter 2 will deal with some specific examples of sustainability indicators in more depth. An important point to make is that the use of simple indicators as a means of following change in complex systems is not new. Biological indicators have been widely employed in environmental science for many years, and in this chapter we compare their use in this context to one of gauging sustainability. The final section of the chapter will draw together some of the main difficulties in using relatively simple indicators to gauge what is, in fact, very complex. These problems will be pursued further in Chapters 2 and 3.

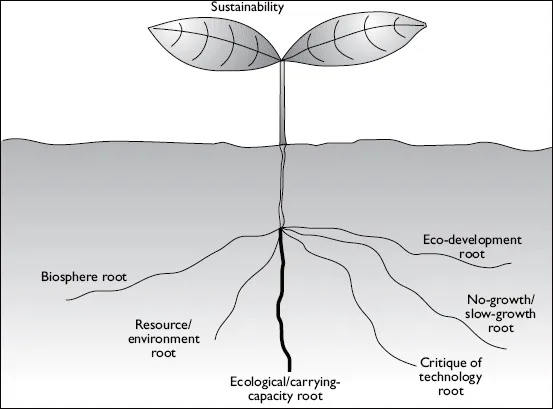

Two roots of sustainability

In its original form, sustainability was closely associated with maintenance of environmental quality, although – as would be expected with a term that is so multifaceted – the origins of sustainability are complex. Excellent discussions can be found in Kidd (1992), Moffatt (1992), Munn (1992), Heinen (1994), Mitcham (1995), McEntire (2005) and Du Pisani (2006) and will not be repeated in depth here. Needless to say, concerns for the environment and views over humankind's place within the environment are ancient. Kidd (1992) suggests that the contemporary view of sustainability in a broad sense has originated from six separate strains of thought (see Figure 1.1).We do not intend to describe each of these; but two of them are particularly relevant for the purposes of this book as they will reappear in various guises in later chapters.

Ecological/carrying-capacity root

Of the six roots in Figure 1.1, a major contribution has come from the first: the ecological concept of carrying capacity and the idea of maximum sustainable yield (MSY) that partly flows from it. Carrying capacity is the notion that an ecological system (ecosystem) can only sustain a certain density (the carrying capacity) of individuals because each individual utilizes resources in that system. Too many individuals (overshooting the carrying capacity) results in overuse of resources and eventual collapse of the population. MSY is a related concept in that it implies a sustainable utilization of a resource. If the MSY is exceeded, perhaps because of population increase or simply because of greed, then the system may collapse with potentially dire consequences for those dependent upon the resource (Botsford et al, 1997; Link et al, 2002).

Source: adapted from Kidd (1992)

Figure 1.1 The roots of the modern view of sustainability

Carrying capacity has been and remains a central concept in ecology (Meadows et al, 2004) and can be found at the heart of the other five strains of thought in Figure 1.1. For example, the second root (‘resource/ environment’) stems from a number of influential books written during the late 1940s and 1950s that question the ability of the Earth to sustain a growing human population. In other words, these works argue that the Earth is approaching its carrying capacity, and great dangers are ahead if we push too close to, or exceed, that limit. In the introduction to one of these books, written by William Vogt and published in 1949 entitled Road to Survival, the author suggests that:

Road to Survival is, I believe, the first attempt – or one of the first – through fully chosen examples, in large part drawn from wide firsthand experience, to show man as part of his total environment, what he is doing to that environment on a world scale, and what that environment is doing to him. (Vogt, 1949)

The critique of technology root

The critique of technology root of sustainability originated during the 1960s and 1970s as a counter to the perceived indiscriminate use and exportation of technologies that may pose dangers to the environment. A classic example is the well-known book by Schumacher entitled Small Is Beautiful:Economics as if People Mattered (1973). There are a number of examples that come under the critique of technology, including nuclear power; but probably some of the best-known examples are in agriculture. Indeed, it can be argued that the problems arising from the indiscriminate use of pesticides, in particular, have had a major effect on the evolution of the sustainability concept. These dangers were highlighted in an immensely influential book, Silent Spring, written by Rachel Carson and published in 1962. The title invokes a spring without songbirds as they become decimated by the widespread use of pesticides. More recently, we have seen a continued concern over the application of genetic engineering within crops and animals and the coining of the term ‘Frankenstein food’ by critics. Indeed, it could be argued that agriculture has been at the heart of much of the sustainability debate, and this is not particularly surprising for two main reasons:

1 Agricultural systems occupy large areas of land – far more land than any other industry with the possible exception of forestry. Therefore, what occurs within agriculture can often have major environmental effects.

2 The end product of agriculture is often food, and we all eat! Agriculture is therefore one of the foundations of human society.

The result has been a move towards the promotion of sustainable agriculture, although terms such as agro-ecology, alternative agriculture, ecological food production, low-input sustainable agriculture (LISA) and organic agriculture have also entered the fray and offer distinctive elements to their proponents. Alternative agriculture is taken to be a sort of antithesis to conventional agriculture without really being very clear as to what either term means (Frans, 1993). LISA is assumed to be sustainable agriculture with an accepted low level of artificial inputs, although where one draws the line between this and high-input agriculture is again rather nebulous. Of all the terms, organic agriculture is the most definable: produce can be certified as organic depending upon the absence of defined substances (mostly pesticides and artificial fertilizers) during production. Indeed, for many the terms sustainable agriculture and organic agriculture have become synonymous precisely because the latter, by definition, minimizes if not eliminates the use of technologies tha...