![]()

Chapter 1

Jonathan Chapman & Nick Gant

Introduction

The Sustainable Design Context

Although sustainable design could be considered a relatively young discipline, general concern for the environment is nothing new; it is possible to trace back observations that describe the impact of human endeavours on the natural world to the 13th century – German theologian Meister Eckhart was amongst the first to identify the emergence of our negative impact on the environment. Ancient animistic cultures considered themselves an integral part of natural systems and had a more direct and symbiotic relationship with Nature, which made their impacts (positive and negative) upon the immediate environment more tangible and visceral, and this undoubtedly affected the way they perceived both the environment, and their place within it. However, in more contemporary situations our species has moved to separate itself from natural systems, turning Nature into an other – the more that Nature is objectified as an external entity, then the more one is separated from it.

Today, perhaps as a direct consequence of our streamlined and automated lifestyles, we seem to place ourselves beyond all this. In the constructed environment, Nature is frequently perceived as an opposing force; a random unpredictable realm in constant rotational flux that must be beaten down and controlled. In contrast, seeing the interrelation between things, the cause and effect and the linkages that connect seemingly disparate elements are all part of a sustainable perception. This extends beyond the disconnected and closed attitudes often adopted by contemporary consumer cultures, to which design contributes. However, we are as dependent today on Nature as we have ever been and the illusion we have constructed around ourselves has deceived us into thinking we have conquered it, and become its masters. Yet, beneath the glossy surface of this mirage of progress ecological decay on an unprecedented scale has been steadily gestating.

So why has sustainability appeared so late on the radar? Perhaps it is because we can now see that the ecological changes happening around us are having an immediate and tangible impact on human health, prosperity and happiness. Furthermore, sustainability is becoming increasingly quantifiable in economic terms. Though this may be cynically perceived as anthropocentrism at work, the move away from the charitable, altruistic guise that is often portrayed by sustainable action may actually be more productive. In addition, climate change and an increase in energy and material cost can no longer be ignored – economically or environmentally.

Within the last 50 years numerous strategic approaches to sustainable design, production and consumption have been developed and deployed, with varying degrees of success. Conventionally, sustainable design is understood as a collection of strategies, which broadly include: products designed for ease of disassembly and recycling; designing with appropriate materials to ensure a reduction in environmental impact; design that optimizes energy consumption and considers options for alternate sources of power; and design that considers longer lasting products both in terms of their physical and emotional endurance, to name but a few. Although there are many strategic approaches to sustainable design that make key contributions to the discipline, it is certainly not all figured out, and essential debate continues to question and explore the most effective ways and means of working with it. This book aims to unpack some of these debates, to both question current approaches and facilitate the pioneering of new strategies.

One thing is for sure: the only universal constant is that of perpetual change. The ebb and flow of the tides, the erosion of the coastline or the continual fluctuation in global temperature – nothing stays the same, and it has always been this way. It is therefore essential that we too continue to evolve and change, as the environment evolves and changes in reaction to us. Indeed, without human presence, the Earth will heal itself, eventually. When described in this way, you could conclude that ‘sustainable design is not rocket science’. After all, the planet doesn’t actually need saving – just saving from us perhaps? So, we just need to find ways that enable us to continue as a species, but in a (more) sustainable way that places as little pressure on the biosphere as (humanly) possible.

Back in the early 20th century, in the heady innovation-days of Henry Ford, the favoured term ‘design’ meant creation, progression, development and the production of newer and better interpretations of everyday life. Today, we are back there, only now it is ‘sustainable’ design that signifies creation, progression and development, and presents the real opportunities for visionaries and heroes to emerge. It could even be said that, in today’s new and enlightened age of sustainable awareness, design has become a lazy and somewhat cosmetic practice that erodes consumer consciousness to nurture promiscuous cultures of more, more and yet more. Yet whether the ‘disease’ or the ‘cure’, once again design has a central role to play in achieving a new and sustainable future. In terms of ‘sustainability’ therefore, design could be seen as the ‘perpetrator’ of whimsy, trend and transience. In this way, it may be asserted that ‘sustainable’ design is the cure – the antithesis of design’s disease-like presence; the stocking-clad superhero that swoops in at the last minute to whisk us off that crumbling ledge.

Sustainable design is about criticism. Essentially, it is an edgy culture that reinvigorates design with the ethos of debate that was once the hallmark of creative practice. Situated well within the comfort zone of an ever-hungry consumer society, the daily throughput of products born of trend-driven design slip quietly through the net, unchallenged, while their ‘sustainable’ counterparts, by default, seem to invite criticism due to their participation in what is a critical process; the ‘wagging finger’ that baulks at any given product failing to achieving 100% sustainability often bullishly attacks any claim of environmental improvement. This mode of disruptive and non-inclusive assault is unnerving to many designers, and does not help to encourage designers to engage in more sustainable practice. Therefore, a less bold designer may remain perfectly content to ‘piggyback’ trends as a means to achieve immunity from such criticism. This could be described simply as ‘lazy’, as comforts await this breed of practitioner through the immediacy, low expectation and overall achievability of this prevailing mode of design. Sustainable design is not about this. Rather, it is a vibrant, dynamic and forward-looking discipline that questions why things are the way they are, and proposes how they could, and should be. Furthermore, for all its demands, sustainable design (beyond ecological benefits) offers creative sustenance, enduring meaning and genuine integrity to those who are willing to engage with it.

It may be proposed that the term sustainable design suggests that it is a ‘thing’, an ‘other’ that must be acquired and learnt in order for it to occur; an ethically enlightened destiny that must be aspired to by those practitioners and researchers who have reached ‘that place’ in their career. In fact, sustainable design can actually happen inadvertently, when it is not meant to. Is this still sustainable design? To put it another way, just because someone does not deliberately set out to achieve it, does not mean that it won’t be achieved. Conversely, just because someone sets out to achieve it, does not necessarily mean that it will be achieved. Thus, the same dichotomy is constructed that is present in all areas of the sustainable debate; namely, is it sustainable or not, green or not, good or not, 100 per cent sustainable or not? Perhaps, therefore, the term ‘sustainable design’ is in itself unhelpful, as it tends to suggest that all other practice is unsustainable, and thus the aforementioned polarizations are further reinforced.

Sustainable design is generally considered a specialist approach to design proper – an extra (yet fully integrated) set of issues to be considered when planning, developing and producing objects, spaces and experiences. This can be non-inclusive (exclusive) and often serves to isolate and marginalize those that do, and those that do not. At this point, a false opposition is often created, where sustainable design and design split into two different camps, with ‘apparently’ different agendas. Despite this dualism, the work of the ‘unsustainable’ design camp is sometimes inadvertently more sustainable than that of the ‘sustainable’ design camp. The fundamentals of efficiency, for example, can often synchronize well with the motivations of sustainable design practice; reductions in material usage, driven primarily by cost, often afford a secondary (yet nonetheless impactful) improvement in sustainability. Speed, too, can be a catalyst to efficiency; the much criticized digital age, with its frictionless action may well take us closer to achieving sustainability than a lawnmower made from reclaimed steel could ever do. A false opposition perhaps, but essential notions of efficiency are often compatible with sustainable systems.

So Why Design Anything at All?

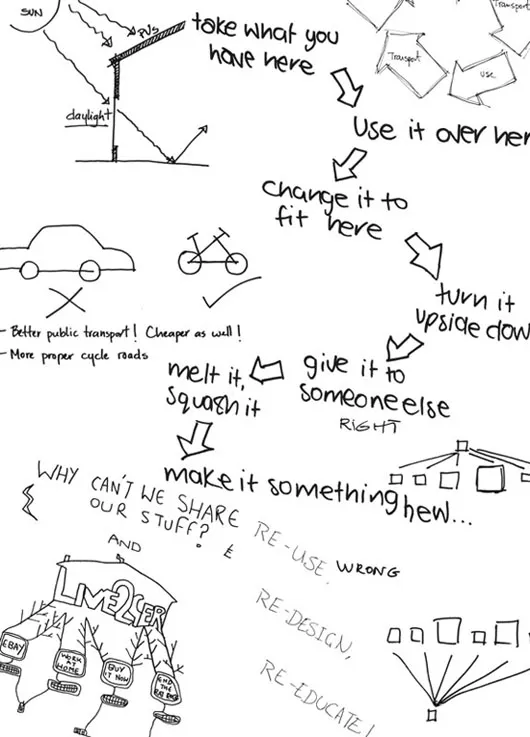

There is a seemingly infinite range of means through which sustainability might be approached, as a designer today. Yet despite this diversity, the damning question poked in the face of most designers when approaching sustainability, is ‘Why design anything at all?’ At first, this might seem like an insightful and appropriate proposal, born as a natural consequence of sustainable design discourse, with its heart so firmly rooted in the reduction and minimization of impact. However, on closer inspection we see that consumption is both a natural and integral facet of human behaviour. Human behaviours are at the motivational core of today’s production and consumption cycles and, as a sustainable designer, you ignore this at your peril. Furthermore, human behaviours should not be seen simply as the cause of all problems. Too often, consumer behaviours are fought against, and the natural train of thought that drives them is rebelled against and boycotted. In this context, one consequence of considering sustainability is often the conclusion not to consume, not to have – and to do without. Yet, this knee-jerk response to the problems we face flies in the face of our deep motivations as a species – to create, to produce and to consume. Problems arise when these deep motivations are expressed physically (e.g. objects, materials and new technologies), as opposed to metaphysically (e.g. stories, ideas and friendships).

In this respect, asking people to stop consuming is a pointless endeavour, when what we should be pursuing is redirective behaviour, which steers consumers towards greener, and more sustainable, alternatives (just as the response to the AIDS pandemic is not to try and stop the world having sex, but rather, to think about safer ways for individuals to go about it). This may well be a more favourable consumer destiny than asking people to do without, which is rather like asking a vampire to stop sucking blood. As with Dracula, our desire to consume is not necessarily our fault, and the sooner we come to terms with this, the sooner we can move forward; doom and gloom cultures of guilt and self-loathing are deeply counterproductive in terms of real progress. Sustainable design methodologies that fail to accommodate human desire are useless unless consumers actually embrace them, engage with them and essentially invest in them.

Is it possible for designers to change human behaviour? The designer’s job is not to sit there and tell people to stop consuming – telling people what they cannot do rarely bears fruit. Design is a needed, necessary and valuable process of invention and innovation, with the potential to take us closer to a sustainable society – a society in which we design for sustainable consumption. As a designer, it is unrealistic to think that you will single-handedly save the world, and to pursue this destiny is hazardous, as it sets up an unachievable (utopian) destiny that guarantees failure. Rather, a designer’s function is to design in a way that (in practical terms) allows for measured, strategic progress. In this sense, consumption must no longer be polarized in terms of to consume, or not to consume – particularly when one considers that in the context of design, the model of non-consumption means to design nothing.

Though the designer’s role clearly has political impact, designers are not politicians. However, if you embrace consumerism then a role is set up for the designer as a facilitator of objects and experiences that through their existence stimulate and steer real sustainable progress. Furthermore, through not consuming, the need for more sustainable products ceases to exist, as if you don’t consume, nothing more gets invented and improved. One could understandably respond to this with the cry of ‘Good!’ Although this is driven by sound intention, the hidden danger is that consumer reality becomes nothing more than an ascetic life sentence, characterized by a noble culture of sacrificial non-enjoyment – not to mention the huge economic transition that this shift implies within a consumer society. The developed and developing worlds are not simply going to stop consuming, and the designer’s role becomes clearer the moment we accept this inevitable fact. The aim therefore must be to design in a way that promotes consumption models of long-term sustainability.

While it would be misguided to advocate the mindless, indiscriminate consumption of products, it would be fair to say that there will always be a need for them (as has been proven through millennia of our species having and possessing material things). So, is designing a recyclable pencil sharpener going to change the world? Perhaps not, but if you strive to accommodate consumer motivation (or lust) with more sustainable products, then improvements are actually being made – and there is considerable room for such improvements in today’s unsustainable world of goods. Designing in a sustainable way is a proactive engagement with the issues, rather than a fanciful dance within an overly optimistic utopia of non-consumption.

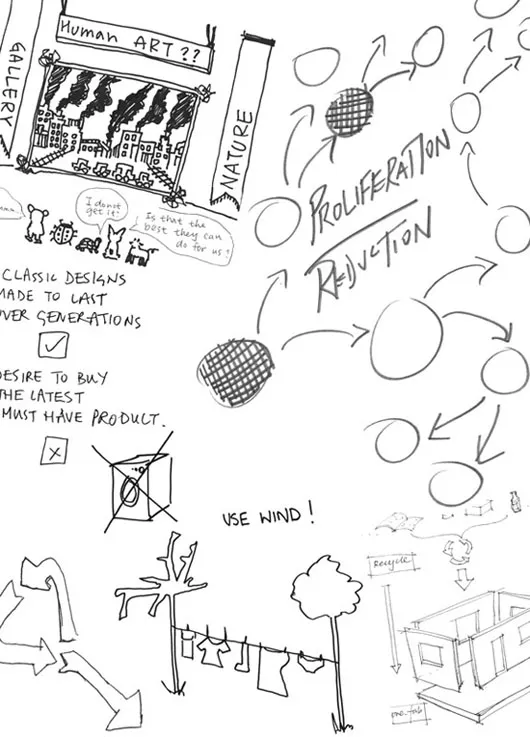

100 Per Cent Sustainable?

Can anything be 100 per cent sustainable? While we still have ice caps, igloos are said to be pretty harmless to the natural world, yet when faced with the everyday demands of commercially driven product design it becomes difficult to imagine how anything manufactured can be truly benign in environmental terms. Everything has an impact of some sort, whether through resource extraction, production, shipping, retailing, use, disposal, recycling and so on. So why ask the question? In an etymological sense, sustainability is an ‘absolute’ term, which implies the total accomplishment of its well-intentioned proposition. In this sense, the sustainability debate should leave little room for discussion. Unfortunately, this approach also adds fuel to the idea that you either are or you ain’t – green or not, sustainable or not. This sweeping overview of reality is grossly unhelpful, as it polarizes what is actually a complex and multifaceted debate. In this way, it can be seen that terminologies such as this are the lowest common denominator where debate is concerned, and unfortunately serve to close down and inhibit discussion, when they should be opening it up and catalysing it.

On the other hand, the idea of 100 per cent sustainability is the ultimate ambition of the sustainable designer; it is the direction we all face, but should do so in the awareness that the term 100 per cent sustainable is as exclusive as it is inclusive. Perhaps a more helpful way of framing this is to consider degrees of sustainability. The questions then become: ‘How sustainable is it?’; ‘How sustainable could it be?’; and ‘How can we make it more sustainable?’ Clearly, new ways of measuring sustainability are greatly needed; ones that are inclusive and participation-widening as a means to engage a broader industry populace. In addition, new means of gauging and mapping sustainability must be more effective in enabling the deeper complexities of the subject to embrace the diversity of creative approaches that might be developed.

In a recent survey staged at the 100 per cent Design exhibition in London (2006), it was found that 53 per cent of those of the design industry that took part in the survey believed that 100 per cent sustainability is possible, whereas 47 per cent felt that it was not. The similarity in these opposing results suggests that consensus is far from reached, and sustainable design practice is driven largely by ‘perception’ as to what is, and what is not effective and achievable. In a field as subjective as design, it is quite understandable that this should be the case. However, these perceptions can become problematic, as they foster the practice of simplistic, symptom-focused paradigms. As such, they tend to incubate popular myths about sustainability, rather than pioneering and adopting a more integrated process that celebrates, through engagement, the complexities and unilateral benefits of a new and creative process that situates sustainability at its centre. It is essential that sustainable design is more than just a box that can be ticked once a recycled material has been specified, or solar cells used, for example. Yes, these changes would make things more sustainable, and any motion towards a more sustainable future should be embraced, but that should not, and must not be where the discussion ends. As a discipline, sustainable design requires a level of engagement that must go beyond these immediate solutions, delving deeper into the multifaceted issues relating to object creation, and applying the same level of rigour that would be expected of any other creative discipline. To be effective, sustainable design must become more than a ‘bolt-on module’ that enables ‘conventional design’ to transcend its current form. If you want to move closer to the notion of 100 per cent sustainability, you must first embrace the discipline itself, on a deeper level and at the earliest possible opportunity; in doing this, by default, you become a sustainable designer.

Today, we live in a strange time. People often think they are being sustainable when they are not, and the attitude of others – fostered by off-putting doom and gloom diatribes of statistical eco-data that bode the end of the world – is to avoid the issue completely due to the apparent hopelessness of it all. This is a symptom of modern times; when there is ignorance, an oversimplification of sophisticated debates occurs that forces generalizations to be made. Percentages are a mode of description that is often used in a similar context to this. The problem with percentages is that there is no accounting for the complexities of scale. Therefore, it is the journey towards, rather than destination, that industry should be focusing on; thinking in terms of ‘ecologies of scale’ is helpful in framing this particular scenario – moving from 9 per cent sustainable to 9.5 per cent sustainable is progress after all. For example, if you are a junior designer working with a successful large-scale global brand, your achievement ...