![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

Wolfgang Lutz and Warren C. Sanderson

While the 20th century was the century of population growth—with the world’s population increasing from 1.6 to 6.1 billion—the 21st century is likely to see the end of world population growth and become the century of population aging. At the moment, we are at the crossroads of these two different demographic regimes, with some countries still experiencing high rates of population growth and others already facing rapid population aging. Demographic changes will make the 21st century like no other. Forecasting these changes, understanding their consequences, and formulating appropriate policies will, indeed, be challenging. This book is a step toward meeting those challenges.

Rapid population growth in the 20th century, and especially the acceleration in the growth rate after World War II, gave rise to notions such as the “population explosion” and associated fears of hunger, socio-economic collapse, and ecological catastrophe. More recently, the prospect of the substantial aging of populations has led to fears that public pension plans will fail and that those countries most affected (mainly in Europe, along with Japan) will enter an era of economic, social, political, and cultural stagnation.

This book deals with the anticipated population trends of the 21st century in a comprehensive manner. It highlights the population dimension that matters most in the context of sustainable development, namely, human capital, which is usually approximated here by level of education. It also attempts to combine methodological innovations (in probabilistic forecasting, multistate projections, and dynamic modeling) with a focus on the most relevant population-related challenges of the century ahead.

New forecasts of world and regional populations are presented here and are combined with an outlook for future human capital in different parts of the world. The picture is complemented by a series of more specific chapters that deal with the key elements of population change in the context of sustainable development, which include studies on the

• interactions between population growth, education, and food security in Ethiopia;

• interactions between HIV prevalence and education in Botswana;

• interactions between urbanization and education in China’s population outlook; and

• the impact of population trends on greenhouse-gas emissions and climate change.

All of these studies were produced in and around the Population Project of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) over the past few years. They were driven by the common agenda of deepening our understanding of the role of population in sustainable development in a model-based and quantitative manner and applying what we learn to forecasting.

The different chapters of this volume are fully consistent with one another, both in terms of serving this goal and in terms of the specific assumptions made in the forecasts presented in the individual chapters. They also provide the basis for a new approach to thinking about population trends. The new concept of population balance, which is discussed in the concluding chapter (Chapter 10), provides a common framework within which to address the challenges associated with both rapid population growth and rapid population aging. These two demographic regimes, at whose intersection we now stand, seem to be very different from one another, but our new analysis shows them to be two sides of the same coin. We do not have two separate phenomena to study—population growth and population aging—but rather a single one, namely, age-structure imbalance that results from specific forms of demographic transition.

The acceleration and subsequent deceleration of population growth, which are a consequence of the universal and ongoing process of demographic transition (which we discuss below), have not occurred simultaneously in all parts of the world. Europe and Japan have been experiencing fertility levels well below the replacement level (an average of around 2.1 births per woman) for two to three decades, while in most of Africa and some parts of Asia more than half the population is under 20 years of age and family size is still above four children per woman. Hence, today we see a demographically divided world in which those countries that are further developed not only have reached very low fertility and high life expectancy, but also have high human capital (education) and high levels of material well-being. The latest entrants into the process of demographic transition not only have lower life expectancy and higher fertility, but also are much more affected by poverty, malnutrition, and lack of education. Although we expect these countries to complete their transitions during the 21st century, low human capital, weak institutions, political instability, and high economic and environmental vulnerability pose significant limits to their prospects for social and economic development in the near term.

The expectation that almost all the countries in the world will complete their demographic transitions by the end of this century is central to the arguments made in this book. Before discussing why we believe this, it is worthwhile to consider different public perceptions about the demographic future. We do this in a rather simple manner by highlighting two of the most prominent, and also most extreme, positions in the public discourse.

1.1 Contrasting Perceptions of the Demographic Future: From “Population Explosion” to “Gray Dawn”

Population and especially the related issues of changing family forms, abortion, and migration are topics on which many people (scientists and nonscientists alike) have strong views. This may be because, unlike many other objects of scientific analysis, these topics directly touch upon the lives of almost everybody. Everyone has a family of origin of one form or another that is of the highest emotional importance. A large number of people either have or are considering having children. Similarly, most people are involved in the labor market and are concerned personally about the security of their pensions. However, even aggregate-level population considerations beyond personal experience and based on abstract reasoning about conditions in the rather distant future tend to excite people. Obviously, questions concerning changes in the size and structure of our own species, our nation, or our ethnic group interest us in a rather existential way. Even many people who do not subscribe to collective goals and who are interested only in the possible implications of population trends for their own welfare believe that, at least in the medium to long run, population trends do matter, be it in terms of population growth or population aging. Since we stand today at the crossroads of two demographic regimes, it is not surprising that people hold deeply felt, but divergent, views about our demographic future.

Since his 1968 book The Population Bomb, which was followed in 1990 by The Population Explosion, Paul Ehrlich has been one of the most vocal proponents of the group of scientists who warn of the disastrous consequences of rapid population growth and the resultant overpopulation. From his biological and ecological background, he has no doubts that “overpopulation is a major factor in problems as diverse as African famines, global warming, acid rain, the threat of nuclear war, the garbage crisis, and the danger of epidemics” (Ehrlich and Ehrlich 1990, p. 238). However, there still is some optimism, as “people can learn to treat growth as the cancer-like disease it is and move toward a sustainable society” (Ehrlich and Ehrlich 1990, p. 23). For them, “there is no question that the population explosion will end soon. What remains in doubt is whether the end will come humanely because birth rates have been lowered, or tragically through rises in death rates” (Ehrlich and Ehrlich 1990, p. 238). “Action to end the population explosion humanely and start a gradual population decline must become a top item on the human agenda” (Ehrlich and Ehrlich 1990, p. 23).

The latest population forecasts presented in this book show that it is likely that world population growth will come to an end during the 21st century and that this “will come humanely because birth rates have been lowered” (Ehrlich and Ehrlich 1990, p. 238). Still, the world’s population is expected to grow by at least two billion before leveling off and possibly beginning to decrease. The end of world population growth is now on the horizon because the past decades have seen significant fertility declines around the world, and these declines are unlikely to stop at the replacement level of around 2.1 children per woman. Armenia, Bahamas, Barbados, Costa Rica, Cuba, Kazakhstan, Mauritius, Seychelles, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Trinadad and Tobago, Tunisia, and Ukraine are among a considerably larger group of developing countries that now have below-replacement fertility (Population Reference Bureau 2003). Indeed, fertility in countries that together account for 45 percent of the total world population is already below the replacement level. Unfortunately, in some parts of the world—mostly in Africa—increasing death rates due to the acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) pandemic have contributed to this new outlook of lower future population growth. But this HIV/AIDS tragedy is not immediately related to overpopulation; actually, the countries hit worst are among the least overpopulated.

The population aging that results from low fertility combined with a general increase in life expectancy is not an issue in Ehrlich’s analysis. This is in sharp contrast to another highly political book concerned with population trends. Gray Dawn by Peter Peterson starts out by saying, “The challenge of global aging, like a massive iceberg, looms ahead. … Lurking beneath the waves, and not yet widely understood, are the wrenching economic and social costs that will accompany this demographic transformation—costs that threaten to bankrupt even the greatest of powers …” (Peterson 1999, pp. 3–4). Referring to Ehrlich, Peterson—a well-known investment banker and former US Secretary of Commerce—describes the change in concern: “Thirty years ago, the future was crowded with babies. Today, it’s crowded with elders” (Peterson 1999, p. 27). He claims that the social transformation associated with the expected massive aging is comparable to some of the great economic and social revolutions of the past. Population aging will constitute an “unprecedented economic burden” (Peterson 1999, p. 31) and make existing pension and health programs “unsustainable” (Peterson 1999, p. 66). Peterson also discusses the necessary policy responses, which range from later retirement to more and better education and raising more children. Although such policies can all be parts of a response, they cannot lead to a reversal of the aging trend in the foreseeable future, as is demonstrated clearly in the projections given below. Landis MacKellar, in a review of Gray Dawn, says that “aging is not a problem so much as it is a predicament. Problems have solutions, predicaments do not” (MacKellar 2000, p. 365).

When reading through these books, one wonders whether the authors are writing about the same world. They express serious population-related concerns, but the differences could hardly be greater. A critical reader might be tempted to conclude that, since both views cannot be right at the same time, both are gross exaggerations and, in reality, population may not matter much in either way. Unfortunately, the view that population growth and aging may cancel each other and thus there is no reason for concern is a simple-minded short circuit. Both aspects refer to genuine population-related concerns that operate at different levels, tend to affect different societies in different intensities at different times, and in some cases even simultaneously burden a country. China may be the most prominent example. Some consider it already “overpopulated,” but around 200 million more people are expected through population momentum (see below), while at the same time the one-child family is already causing serious problems in terms of the support of the rapidly increasing number of elderly. Indeed, during the first part of the 21st century, a large number of countries will experience population growth and aging simultaneously.

The demographic divide between young and still-growing populations, on the one hand, and rapidly aging and even shrinking populations, on the other, means that we are living in a seemingly paradoxical situation, which tends to confuse commentators who do not know whether they should be in favor of lower or higher fertility. Such seemingly contradictory developments and concerns cannot be explained adequately by one or the other of the existing conventional analytical frameworks used to study population. What is required is a new, broader, multidimensional population paradigm. In Chapter 10 of this book, we offer such a paradigm, which we call “population balance.” Unlike older concepts such as “population stabilization” that narrowly focus on population size, population balance simultaneously takes population size, age structure, and the educational composition of the population into account.

1.2 The Continuing Demographic Transition

How can we understand such a demographically diverse world, and how can we make meaningful assumptions for the future? How can we find the right policies to respond to trends that pose different challenges in different parts of the world? Since the answers to these questions always refer to the secular process of demographic transition, which was the reason for the “population explosion” in the 20th century and is the basis for our expectation of an end to the growth in world population in the 21st century, we start this volume with a short description of the nature of this demographic transition process.

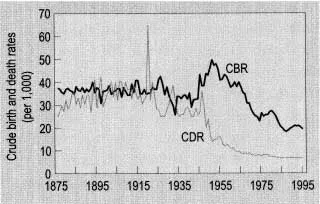

The demographic transition began in today’s more developed countries (MDCs) in the late 18th and 19th centuries and spread to today’s less developed countries (LDCs) in the last half of the 20th century (Notestein 1945; Davis 1954, 1991; Coale 1973). The conventional theory of demographic transition predicts that as living standards rise and health conditions improve, mortality rates decline and then, somewhat later, fertility rates decline. Demographic transition theory has evolved as a generalization of the typical sequence of events in what are now MDCs, in which mortality rates declined comparatively gradually from the late 1700s and more rapidly in the late 1800s, and in which, after a varying lag of up to 100 years, fertility rates declined as well. Different societies experienced the transition in different ways, and today various regions of the world are following distinctive paths (Tabah 1989). Nonetheless, the broad result was, and is, a gradual transition from a smaller, slowly growing population with high mortality and high fertility rates to a larger, slowly growing or even slowly shrinking population with low mortality and low fertility rates. During the transition itself, population growth accelerates because the decline in death rates precedes the decline in birth rates.

A number of theories of the causal structure of the demographic transition have appeared in the literature. An excellent review of these is given in Kirk (1996). Kirk examined economic theories of the transition, the anthropological theories of Caldwell, cultural and ideational theories, historical views, the role of the government, and the role of diffusion. He concluded, “No unique cause exists. Perhaps all aspects of modernization may be described as related to the demographic transition, which in itself is an essential part of modernization” (Kirk 1996, p. 380).

In the same article, Kirk (1996, pp. 381–383) provides eight summary propositions about the state of the demographic transition today:

Figure 1.1. Crude birth rate (CBR) and crude death rate (CDR) in Mauritius since 1875. Source: Mauritius Central Statistical Office.

• “given a modicum of domestic and international peace, m...