![]()

CHAPTER 1

Start At The End — 'What'

What Do You Want to Achieve?

A cure for cancer?

World peace?

Let’s zoom in a bit to something more realistic. What about:

- Keeping the rise in global average temperature to below 2 degrees C?

- Halving the proportion of people whose income is less than $1.25 a day?

- All water bodies in a particular catchment having a healthy natural species range and abundance of plants, invertebrates and fish?

- A circular economy?

- Protecting and maintaining the ecosystems services provided in a particular area?

These are all classic ‘wicked problems’: complex, systemic, with lots of uncertainty and no clear solutions that do not also have downsides for some people (Rittel and Webber, 1973). Problems like maintaining ecosystem services or limiting global temperature rises, embody the Tragedy of the Commons (Hardin, 1968): a common resource will be exploited, perfectly rationally, by each individual who has access to it, until it crashes. Sustainable use of a common resource will only come with active management of access to that resource. (Another solution is to privatise it: pretty hard with the atmosphere.)

GoodCo Fish Ltd can decide, altruistically, to stop catching North Atlantic cod because stocks are dangerously low. But if NastyNets Inc. continue to exploit the fishery, GoodCo Ltd’s self-regulation is merely symbolic: noble but ineffective at protecting the endangered cod.

The landlord of a building could invest in making it more energy efficient, but if the tenant pays the energy bills directly then the landlord has no incentive to do so. If the bills are rolled up in the rent, the tenant has no incentive to use energy more efficiently. The Sustainable Shipping Initiative recognises this problem of split incentives: ‘charterers of energy upgraded vessels stand to save on fuel bunker costs but if owners are not confident that charterers will share these savings, they are unlikely to make the capital investment up front’ (Sustainable Shipping Initiative, 2012).

If the outcome you want to achieve requires change at the level of the system, if there’s a resource held in common, or if there are split incentives, then what’s needed are collective, collaborative approaches where many players act simultaneously.

They can’t be solved by one person or organisation acting alone. The positive outcomes can only be achieved by working with others. Collaboration is the key to unlocking our potential as the generation which takes these problems out of the ‘too difficult’ box and works out how to solve them, together.

Not everything you want to achieve requires collaboration. That’s a good thing, because collaboration is hard! It is slow, inherently uncertain and it means sharing control. And it depends on there being willing collaborators who want the same outcome that you do (or, at least, complementary outcomes). So like a fellowship of mismatched heroes setting out on a perilous quest, you should only do it if the prize is worth the pain.

Collaborative advantage

The cost–benefit judgement depends on understanding the potential collaborative advantage: the extra you can (only) achieve by working with others, rather than working alone (Huxham, 1993). Huxham waxes rather lyrical:

Collaborative advantage will be achieved when something unusually creative is produced – perhaps an objective is met – that no organization could have produced on its own and when each organization, through the collaboration, is able to achieve its own objectives better than it could alone.

But it’s even better than that! Huxham goes on:

In some cases, it should also be possible to achieve some higher-level … objectives for society as a whole rather than just for the participating organizations.

So collaborative advantage is that truly sweet spot, when not only do you meet goals of your own that you wouldn’t be able to otherwise, you can also make things better for people and the planet. Definitely sustainable development territory.

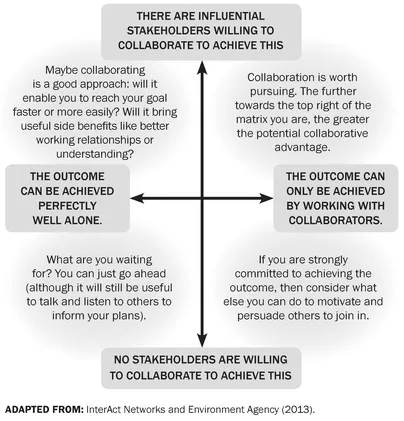

FIGURE 1. Is collaboration a good approach for this outcome?

Looking at Figure 1, there’s another side to the collaborative advantage coin. If the potential collaborative advantage is not high enough, or you can achieve your goals just as well working alone, then it may be that collaboration is not the best approach. You can think of it like this:

The nature of the outcome you are trying to achieve will allow you to map it along the horizontal axis. How wicked, systemic and entrenched is the status quo?

You can make a guess about what other people and organisations want, to do your initial placing along the vertical axis. You may already have had some tentative conversations with people who share your ambition and want to do something, and who realise they’ll be more successful acting together. The early exploratory phase (see Figure 1) will help you understand better whether collaboration has potential.

Complementary outcomes

It’s likely that other organisations have got an interest in the same issues as you – but they may be looking at it from an entirely different perspective.

The Prince of Wales’ Corporate Leaders Group on Climate Change (Corporate Leaders Group) are all from big businesses, so at first sight you might think they all had the same interest, but Craig Bennett, who was Director of the Corporate Leaders Group from 2007 to 2010, explains that they had subtly different needs:

I think there were five different sets of motivation, depending on the nature of the business. The heavy emitters knew their businesses would need to change, and wanted some long-term understanding of how that was likely to happen. The technology companies could see an opportunity in low carbon innovation and wanted to accelerate it. Consumer-facing companies were concerned about security in their supply chains as well as public perception and wanted to be seen as leaders. Banks could see that there were big-picture economic changes coming, and wanted to be part of shaping the new paradigm. Finally, utilities wanted to get debate and action around adapting to climate change.

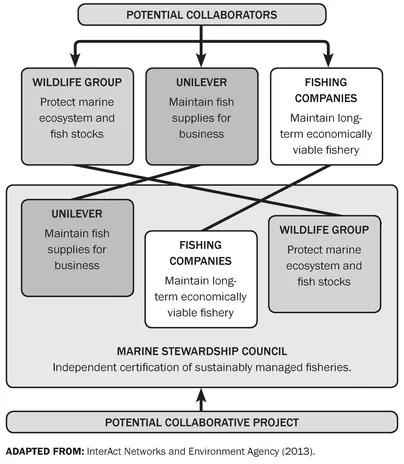

FIGURE 2. Many outcomes, one project.

Complementary outcomes were also essential to the success of the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC), see Figure 2. When the MSC was founded Unilever wanted to secure supplies for its international fish business far into the future but could see that there wouldn’t be enough fish in the sea for it to meet its business ambitions. WWF wanted to reverse dramatic declines in global fish stocks and protect marine ecosystems threatened by overfishing. A breakthrough came when a small group of fishing and seafood processing companies (the early adopters) began to see that their own interests, of retaining economically viable fisheries now and into the future, could be met only through collaboration in a green-business enterprise offering market-based incentives. Their desired outcomes were complementary, rather than identical. They worked out a way of meeting all three sets of interests simultaneously.

![]()

CHAPTER 2

Who Might Collaborate With You?

YOU KNOW THAT WHAT YOU WANT TO ACHIEVE can only be done with others. You’ve made a first guess that perhaps there are influential potential collaborators out there who might collaborate with you. This is the beginning of the who strand.

You also need to:

- Turn that guess into hard facts.

- Begin to understand the complementary skills, constituencies and responsibilities the collaboration needs.

- Assemble a team that can shift the system, which includes the right kinds of leadership.

Bringing together the eventual collaborators can be a long and frustrating phase, when you may not feel as if you are making much progress. Dead-ends, red herrings, people who are supportive in principle but not in practice, having what feels like the same conversation a number of times. This is normal!

Wessex Water’s Fiona Bowles had a challenge when approaching stakeholders for their collaboration in the Frome and Piddle Catchment Pilot. (These pilots experimented with addressing water quality and other problems at a ‘catchment’ level – that is, a scale bigger than individual rivers or lakes, but smaller than entire river basins.)

Whilst we work regularly with farmers to protect our water supply sources, we found it hard to find farmers or farming organisations who would undertake to represent the views of this interest group on the initial steering group. Once the issues were identified they were more keen to engage.

Guesses into evidence

Don’t neglect the obvious desk research: who are the players and commentators, critics and pioneers with an interest in the issue...